Artist Project / Embassies and Consulates

Heman Chong

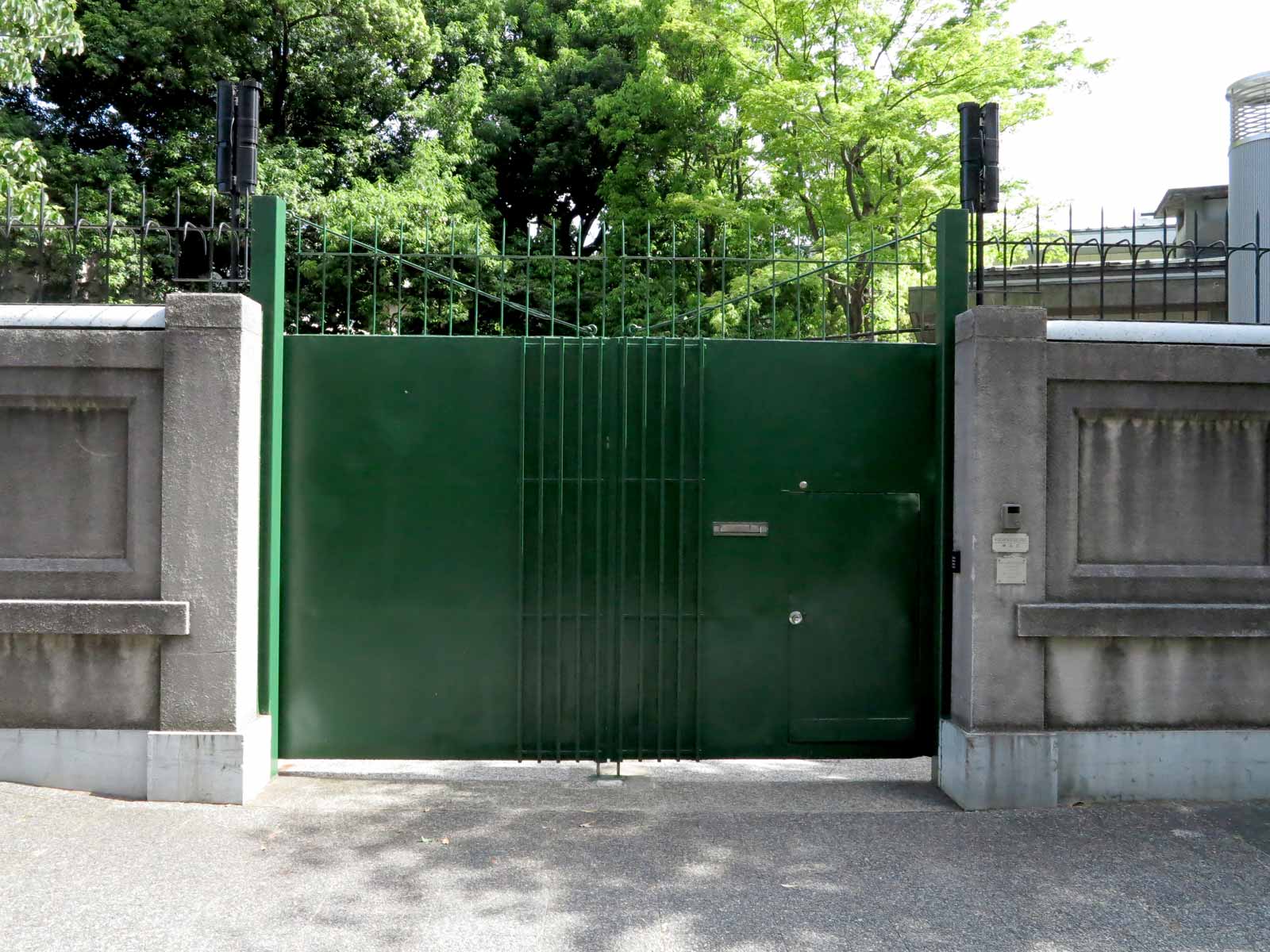

The first door was in Tokyo, in the Roppongi district. He said he discovered it in a state of boredom, or more exactly, in that mental state that walking in Tokyo is particularly inclined to produce—a state of visual overstimulation that is like boredom, but also strangely close to a kind of hypersensitivity, a readiness to see a hidden order suddenly emerge in the dense life of the city. The door that captured his attention had been placed across a blind alleyway. It had no special features, but was remarkable for being unmarked, without a name, bell, or knocker. Oddly, the cracked cinderblocks that framed the door on either side seemed older than the buildings that they abutted. Behind the door were the branches of some trees, giving the entire scene the hint of a hortus conclusus, a walled garden in a neighborhood that was not known for being green. An electrical conduit snaked along the pavement and over the wall.

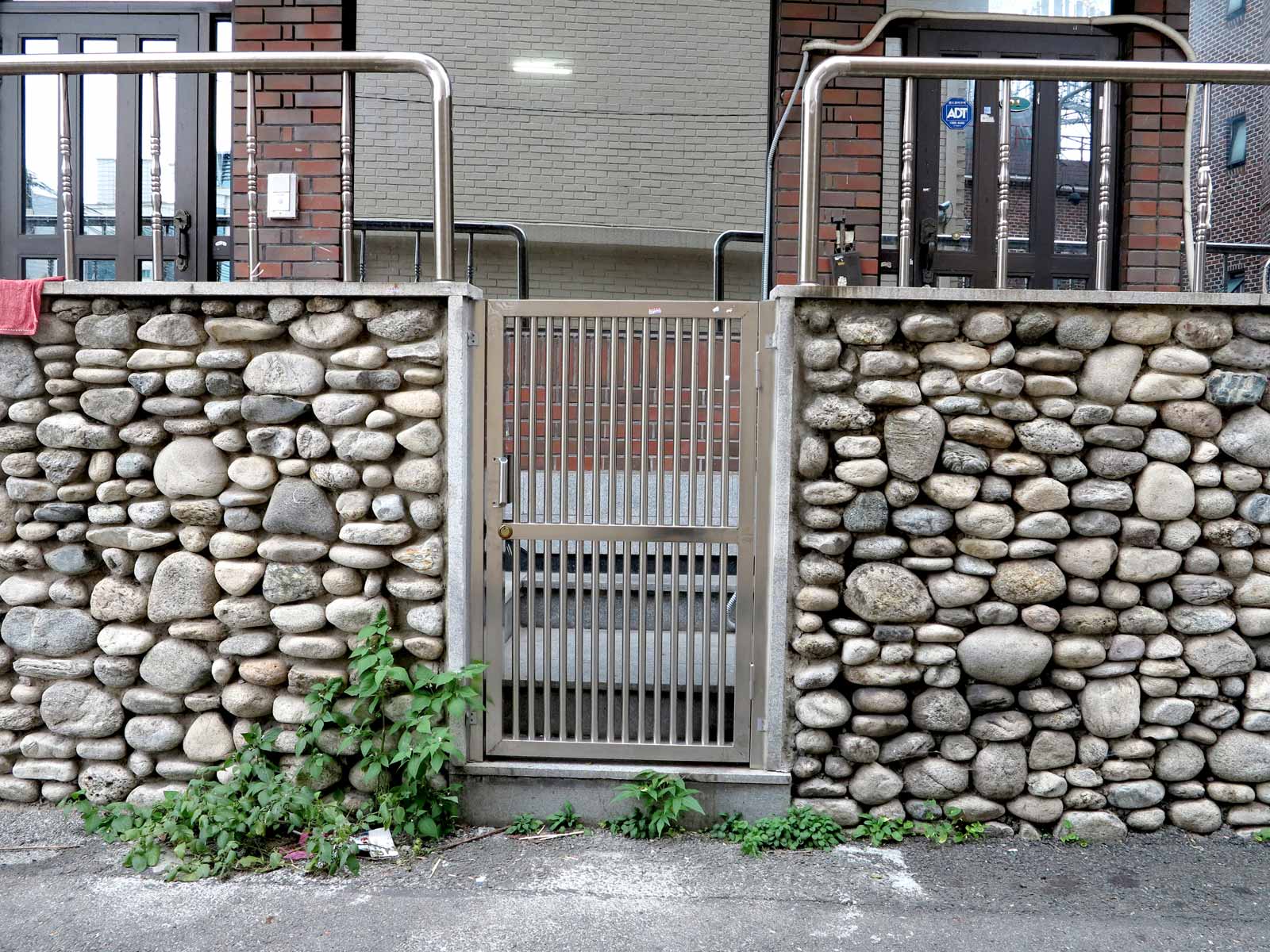

Heman Chong’s photograph of the door would become the first in his ongoing series documenting the back entrances of embassies and consulates—over three hundred of them since that first encounter in 2018. Almost all embassies and consulates have back doors. They are service entrances, but they also provide a discreet means of entering or leaving the building. And yet, even though the doors do nothing to announce themselves, behind them is the sovereign territory of a foreign country. Every one of these anonymous thresholds represents a national border. Stepping across the threshold immediately brings a change to the legal status of the visitor. It stands to reason that such doors appear frequently in spy novels, for they reek of conspiracy. According to Chong’s observations, the only country that routinely labels its back door is Switzerland. The most discreet doors are set so flush into the wall that they disappear, or take the form of unmarked metal gates. There are sometimes garbage bins placed prominently in front, but there is never any of the trash that indicates lively human activity.

Surprisingly, in many cases, national style manages to persist even in these self-effacing frames. Perhaps this can partly be accounted for by the convention that architects who build an embassy are selected from back home, as is, for security reasons, the construction team. Even when the embassy is in a converted building—in an old restaurant, a villa, or a dentist’s office—renovations are done by contractors from the home country. It is perhaps for this reason that the back door to an Italian embassy in East Asia might be inclined to show a little wrought iron, or that South American embassies everywhere maintain a kind of high-modernist flair, even in their use of razor wire. You could write a history of regional style here, but it would also need to be a history of insecurity, from the primitive functionalism of the combination of opaque door and steel gate to the infrared CCTV and retractable, attack-resistant bollards of more pugilistic states.

Taxonomies of regional architecture aside, there is, despite their reticence, a latent tension in these photographs. The doors are both the subject of the image and obstructions in the image. We are clearly invited to scrutinize the doors, to compare them and contrast them, but also to contemplate the voids that lie behind them, the spaces that we cannot see. But are these varied mysteries, or do the doors all ultimately lead to the same undifferentiated space? We have to ask if there is a lingering obsession at play here, considering that the images in Heman Chong’s previous photographic series, “Calendars (2020–2096),” were also as much defined by what they did not contain as by what they did. That series depicted public places with no people in them. On the busy island of Singapore, this is extremely difficult to achieve. Capturing such moments involves working like a wildlife photographer: rising before dawn, or waiting for many hours until the anticipated opportunity arises. The empty plazas become like theatrical sets, with all the charge of an empty stage. Likewise, these back doors carry something of the malignant energy of props: they have just slammed shut, or—perhaps worse—are just about to open.

—Adam Jasper

Heman Chong’s work was exhibited at M+ Museum, Hong Kong, in 2021, and he was artist-in-residence at Swiss Institute, New York, in spring 2022. He is the co-director and co-founder (with Renée Staal) of the Library of Unread Books. He can be found on YouTube at youtube.com/c/AmbientWalking.

Adam Jasper is an architectural historian and art critic. He is currently an assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.