How to Make a Monster

Goya and the perils of excessive reason

George Prochnik

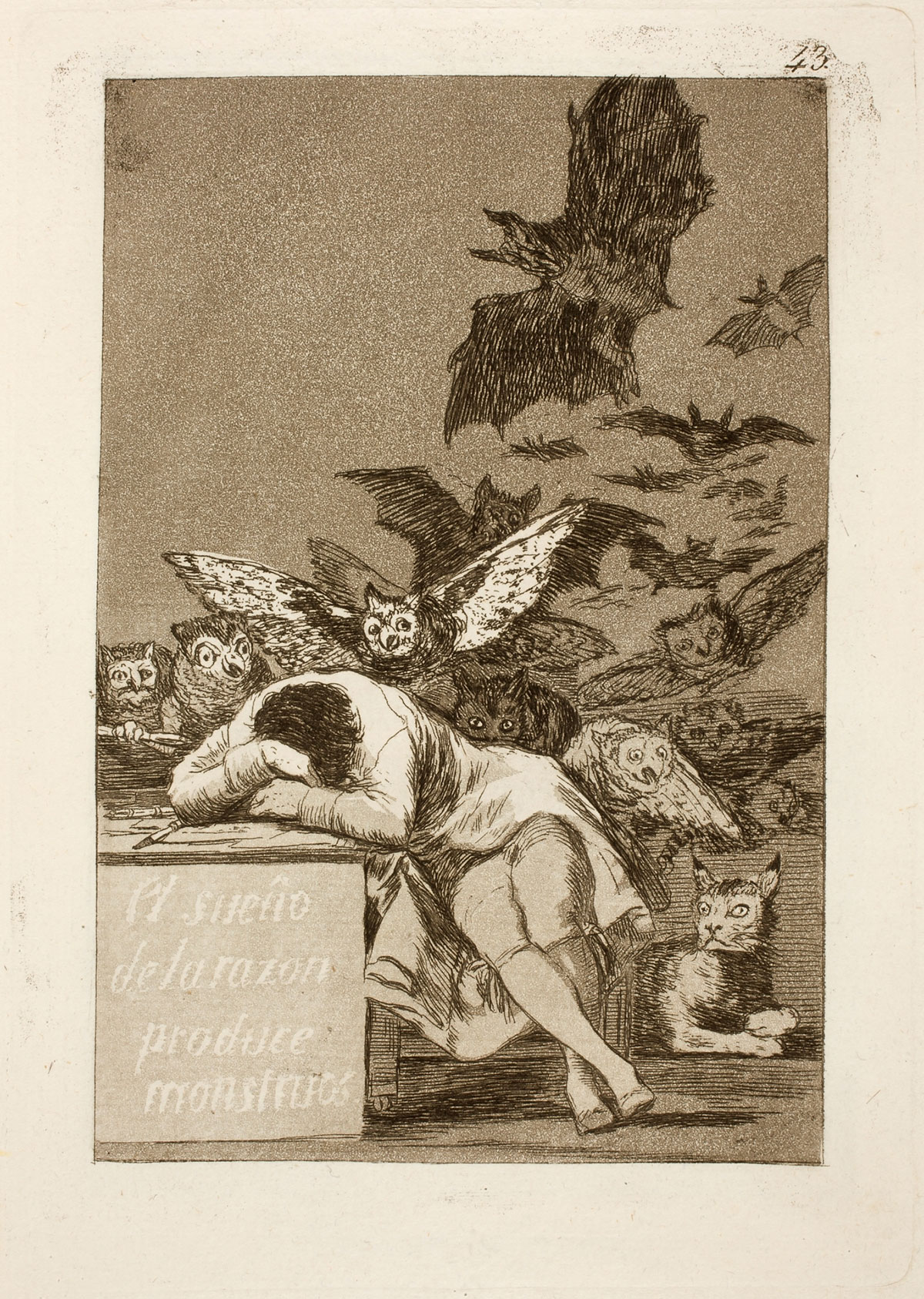

The picture depicts a man seated beside a stone desk with his head buried in his arms on scattered papers. Myriad animals hover behind his slumped back: wide-eyed owls with fluttering wings, big bats in mid-flight, a black cat, and a lynx. Inscribed on the desk is the following phrase: el sueño de la razon produce monstros, usually translated as “The sleep of reason produces monsters.”

Goya himself was plainly inspired by the finished work. Having four years earlier passed through a grave illness (probably lead poisoning) that left him deaf, dizzy, and subject to hallucinations, he went off on a creative jag after making it. He titled the resulting series of eighty prints Los Caprichos—“the caprices” or “plays of the imagination”—and took out an advertisement for it in the Diario de Madrid:

The author is convinced that it is as proper for painting to criticize human error and vice as for poetry and prose to do so. … He has selected from amongst the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society, and from the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance, or self-interest have made usual, those subjects which he feels to be the most suitable material for satire, and which, at the same time, stimulate the artist’s imagination.

Goya situated himself among Spain’s Enlightenment thinkers, a proponent of human reason against the dark illusions of superstition. He had a particular animosity for abuses perpetrated by the Catholic Church, which manipulated the people’s prejudices and fears to keep them submissive, and many of the Caprichos explicitly mock the clergy. It seems we can now penetrate the mystery of that haunting print. Goya is warning us about the horrors that breed when the rational mind dozes off. We must be vigilant, keeping reason wide awake against the monstrosities spawned by ignorance.

The idea carries a righteous, straightforward political message. Billy Bragg, the British protest singer, adopted it in a song from 2017:

In the end the greatest threat faced by democracy

Isn’t fascism or fanaticism

But our own complacency…

Best pay attention

For there’s simply no guarantee

Of a happy ending to history

And the sleep of reason produces monsters.

Clarity. “Wokeness.” Democratic activism. All politically inspiring ideas.

Only the more we know about Goya’s print, the murkier its message becomes, until it’s uncertain what dangers he is portraying, let alone how their menace might be opposed.

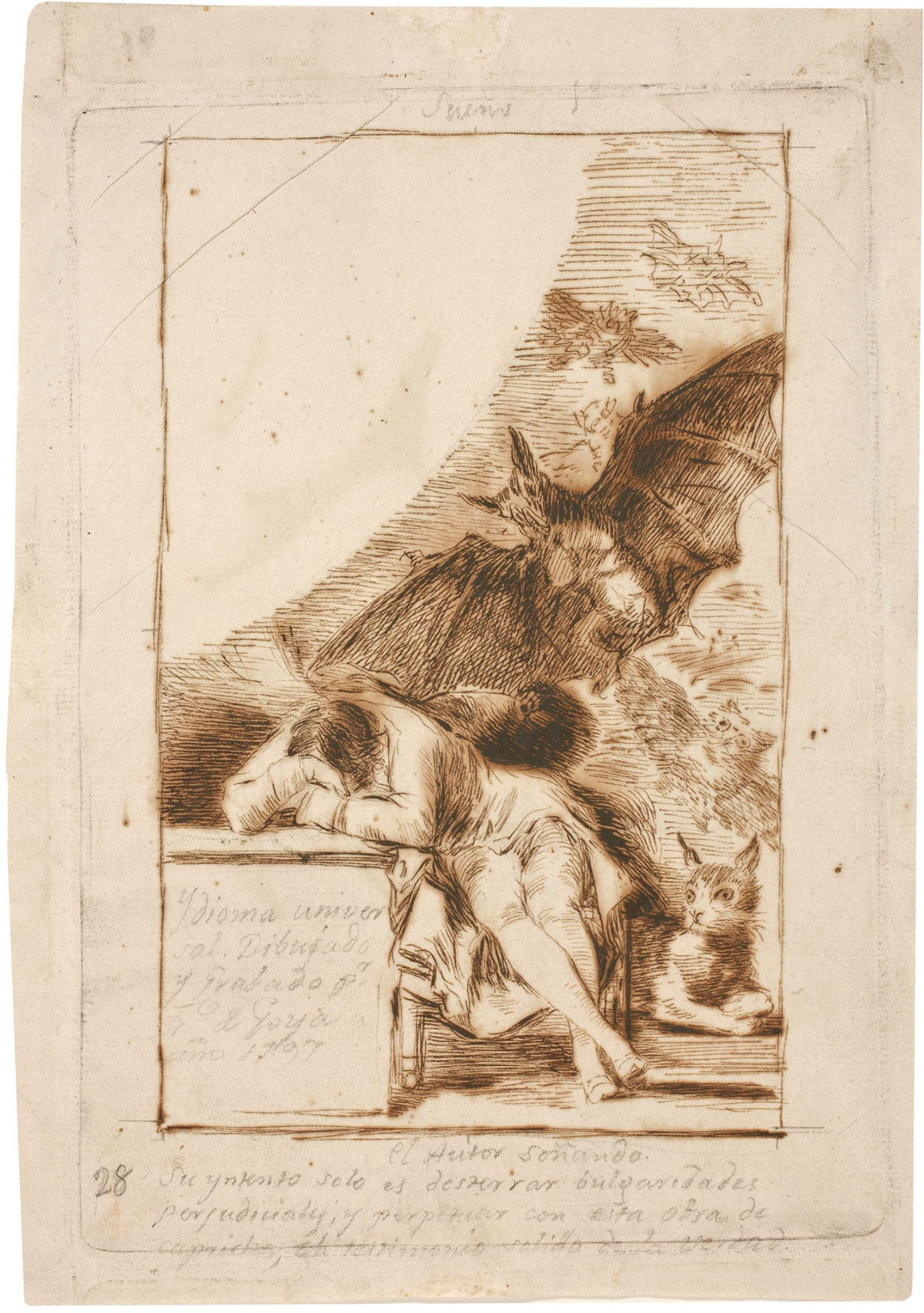

Goya’s preliminary drawings for the etching add perspective. In one, the male figure’s face is partly visible, and proves to be none other than Goya himself. While a few bats fly in the air behind him, numerous disturbing human faces billow forth as well, some of which appear to be versions of Goya’s own self-portrait. The monsters this figure is plagued by seem to be nightmares of himself.

In another, the bats have multiplied, while the other faces are gone from the sky. The inscription here reads, Ydioma universal: Universal language. Beneath, Goya scrawled, “The author dreaming. His only purpose is to root out harmful ideas, commonly believed, and to perpetuate with the work of the Caprichos the soundly based testimony of truth.” But in what conceivable way does the image of a dreaming man under attack by a giant bat perpetuate the cause of truth?

The Enlightenment argued that Truth was the universal language. Yet, if rooting out noxious ideas was the artist’s only goal, this image might signal the abject failure of that project. While the final print ostensibly shows what happens when reason is interrupted—the monsters of deceit and delusion swoop in to fill that void—here, the man dreaming of enlightenment himself apparently creates the dark visions swarming above him. Can Reason itself become excessive? Can it overreach to the point where it generates its own species of monsters?

Some of history’s most ambitious reimaginings of the social order have suffered from the gross overconfidence of their creators in the potency of their own rational intelligence. (Consider the neoconservative case for war in Iraq.) Was our current political nightmare really produced because most of the electorate was snoozing? How does that slumber jibe with the enormous upswell of energy among young voters supporting an openly socialist American candidate? Might our Monster-in-chief in fact be the product of hyper-rational politicians from both mainstream parties, who manipulated the democratic system to satisfy their greed and lust for power? Is Goya, in fact, meditating on what monstrousness really consists in, and asking us not to wake up, but to look hard in the mirror, and seize our dreams back from the realm of nightmares?

What transforms the monster back into an owl of wisdom?

In this sense, Goya’s etching articulates the actual identity of our misbegotten fears. Perhaps his image retains the power it does not because the animals are mysterious, but because the state of tortured despair of the human figure is so familiar. With his face obscured, and his weirdly twisted body, the individual at the center of Goya’s print might himself be a monster, dreamed up by the natural beasts around him.

In which case, the real task before us today—culturally, artistically, and politically—might be to reimagine our character from the perspective of the world’s non-human creatures: the birds, cats, and bats we’d see if we finally lifted our heads from our desks.

This article was amended on 19 November 2019. Goya was fifty-one years old when he began his famed etching, not thirty years old as was originally stated in the article.

George Prochnik is an author based in London. His most recent book, Stranger in a Strange Land: Searching for Gershom Scholem and Jerusalem (Other Press, 2016), was a New York Times “Editor’s Choice” and was shortlisted for the Wingate Prize in the UK. His previous book, The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World (Other Press, 2014), received the National Jewish Book Award for Biography/Memoir. Prochnik is also the author of In Pursuit of Silence: Listening for Meaning in a World of Noise (Anchor Books, 2010) and Putnam Camp: Sigmund Freud, James Jackson Putnam and the Purpose of American Psychology (Other Press, 2006). An editor-at-large for Cabinet magazine, Prochnik is currently finishing a biography of Heinrich Heine.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.