Evolving out of the Virtual Mud: An Interview with Ed Burton

The imaginary Galapagos of sodaconstructor

Margaret Wertheim and Ed Burton

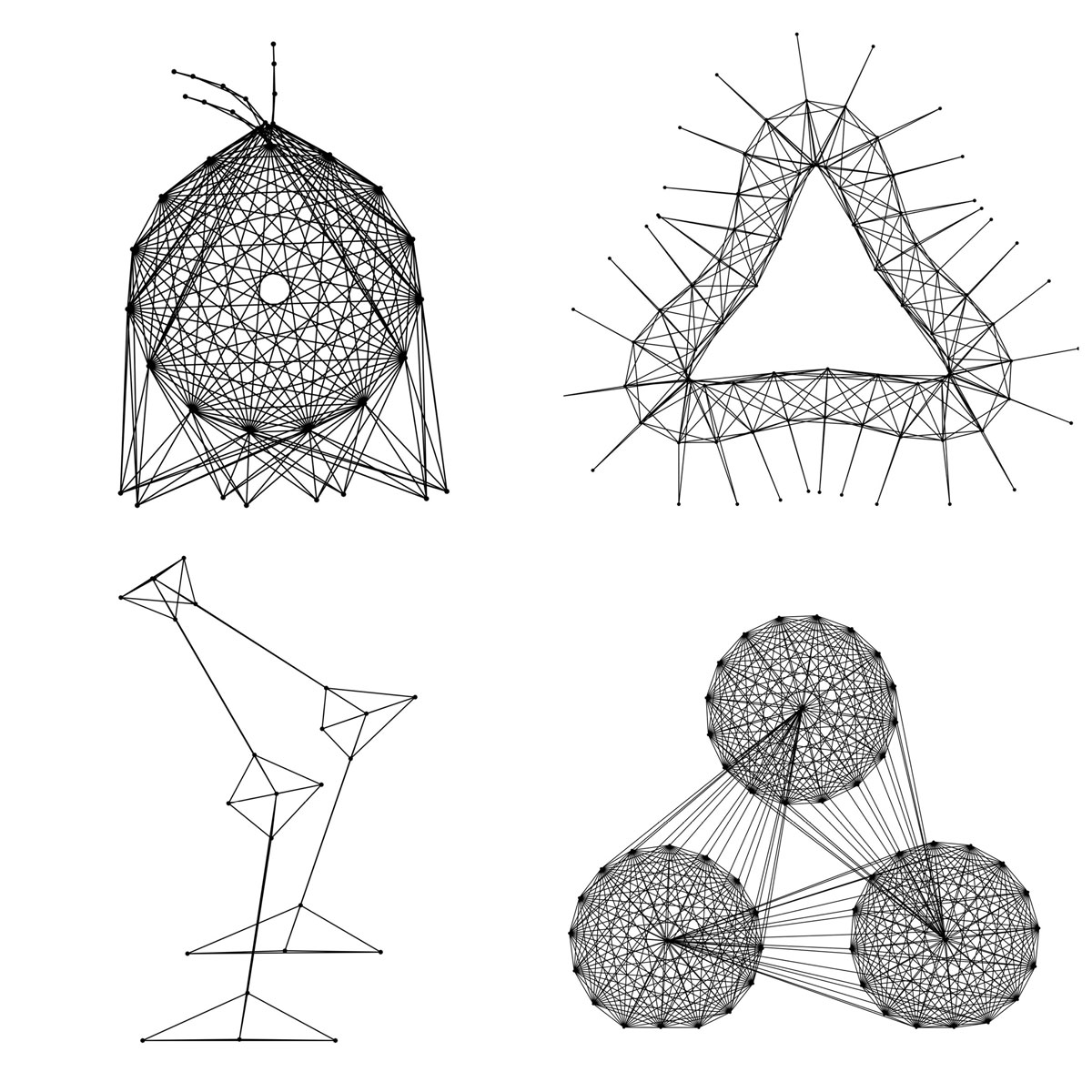

They crawl, they hop, they slink, and they undulate. Some roll, some fly, and others unfold from a simple triangle. These “creatures” are the products of an imaginative evolutionary experiment that now involves more than 100,000 people worldwide. Each of these forms has been created through a program called sodaconstructor that enables users to build models which increasingly resemble living organisms. Over the past five years, a global community has brought forth from this digital mud a Cambrian explosion of species: walkers, stalkers, floaters, and flyers; things that tumble and skip; simulations of spiders, crabs, and starfish; monopeds, bipeds, tripeds, and centipeds; a Möbius strip that turns itself inside out, and a hyperactive “butterfly” enigmatically titled “Love.” This imaginary Galapagos resides on a server in a warehouse in the Shoreditch area of London’s East End, the grunge-chic office of Soda Creative, a company that specializes in producing software at the boundary of art, learning, and play.

The architect of this virtual world is Ed Burton, an artist and computer programmer who serves as Soda’s research and development director. A graduate of the Center for Electronic Arts at Middlesex University, Burton was inspired by computer pioneer Seymour Papert’s constructivist notion of “creative play” and by the engineering principles of Control and Dynamic Systems. To his surprise, the software has turned out to enable a far richer range of possibilities than he had ever dreamed, as users have found ways to subvert and exploit features of the code Burton had thought were inviolable. As in the natural world, the taxonomy of soda-organisms has evolved in ways unimaginable at the start, while Burton—an accidental god—has watched on in wonder at the fecund spirit animating this miniature cosmos. In July, he gave a talk at the Institute For Figuring in Los Angeles. Before that event, Institute director Margaret Wertheim interviewed him by phone from London.

Cabinet: How did you come to design sodaconstructor?

Ed Burton: I had just joined Soda Creative, who were doing a lot of software in a language called Java that I’d never used before. So I needed to learn this quickly, and the way I like to learn things is to play. Essentially, I thought up sodaconstructor as a toy I could build in Java and play with.

What kind of a toy is it?

It’s in the tradition of a construction toy. You create a set of points and join them together by lines that effectively act like springs and you can play around with all sorts of configurations and see how these different models behave within the world. The world itself has some very basic physics programmed into it, such as a simple simulation of gravity. The thing I never anticipated was the diversity of forms you could build with just this simple set of rules.

Can you describe how one of these models works?

Sodaconstructor is a two-dimensional world populated by points and lines. The points represent masses, and the lines represent springs. In the real world, springs usually have a fixed rest-length. The novel element I introduced in the software is to have some of the springs change their rest length over time. You can think of the springs as a bit like muscles expanding and contracting. The change is driven by a sine wave that is programmed into the world and acts like a clock within this space. By connecting the point masses in various configurations and letting the structure flex freely under the influence of this wave, it was possible to make simple walking creatures. I suppose that was the height of my ambition—to make simple things that walked.

So you were trying to make a virtual version of a mechanical toy like Mechano or an Erector Set?

Actually, it’s difficult to think of a physical toy that is like this. Most mechanical vehicles tend to have wheels because wheels are easy to build out of cogs. But typically in nature you don’t get wheels. I was thinking of something more biological.

How did other users get involved with the program?

At Soda Creative, we originally put it up online in 1997. But it went into a very discreet corner of the site and was essentially unnoticed for several years. In the summer of 2000, we gave the site a polish and made it more prominent, then quite spontaneously it started to attract an exponentially growing amount of interest. It was largely a viral process. Suddenly, it washed around the world and we started to see very quickly all these different kinds of creations coming in.

Many of these models seem organic; it’s almost as if they are alive. They also seem to come in distinct types or “species.” Could you describe some of these types?

One type has come to be called amoebas. Essentially, an amoeba is a ball that locomotes by squashing itself along a rotating axis. I don’t know if there’s anything in nature it would be like. That’s one of the few types that dates back to the first batch of models I made. Since then, our users have come up with many different kinds of amoebas and a lot of other types I never imagined. There’s a whole style of models based on intermeshed circles and Möbius strips, and there are many, many different types of walking models, far more sophisticated than anything I envisaged. For instance, bipeds. I suppose I had aspired to create bipeds, but they always struck me as much too difficult.

What’s so hard about bipedal motion?

When bipeds walk, they are constantly out of balance, so to achieve this style of motion requires dynamic balance with active feedback to keep from falling over. In fact, I found a forum where someone said that sodaconstructor would never create bipedal motion because there wasn’t any active feedback from the environment. But our users have managed to make very effective bipeds by exploiting the fact that as a biped falls forward, it gets a slightly better grip on the ground which enables its feet to accelerate slightly. In effect, as it falls forward, it’s able to right itself automatically. It’s interesting that users were able to make a sort of patented method for dynamic balance.

Do you think they were consciously thinking of this as an engineering problem or just hit upon the method accidentally?

It would have to be fairly conscious and a prolonged process of trial and error. The way things get made in sodaconstructor, it’s not that you just think, “Ah, I can make this” and draw it on the screen, and there it is. Things have to be built slowly, through discovering the dynamics of individual experiments and then building up slowly to create more sophisticated things. Something like balanced bipeds requires lots of experimentation.

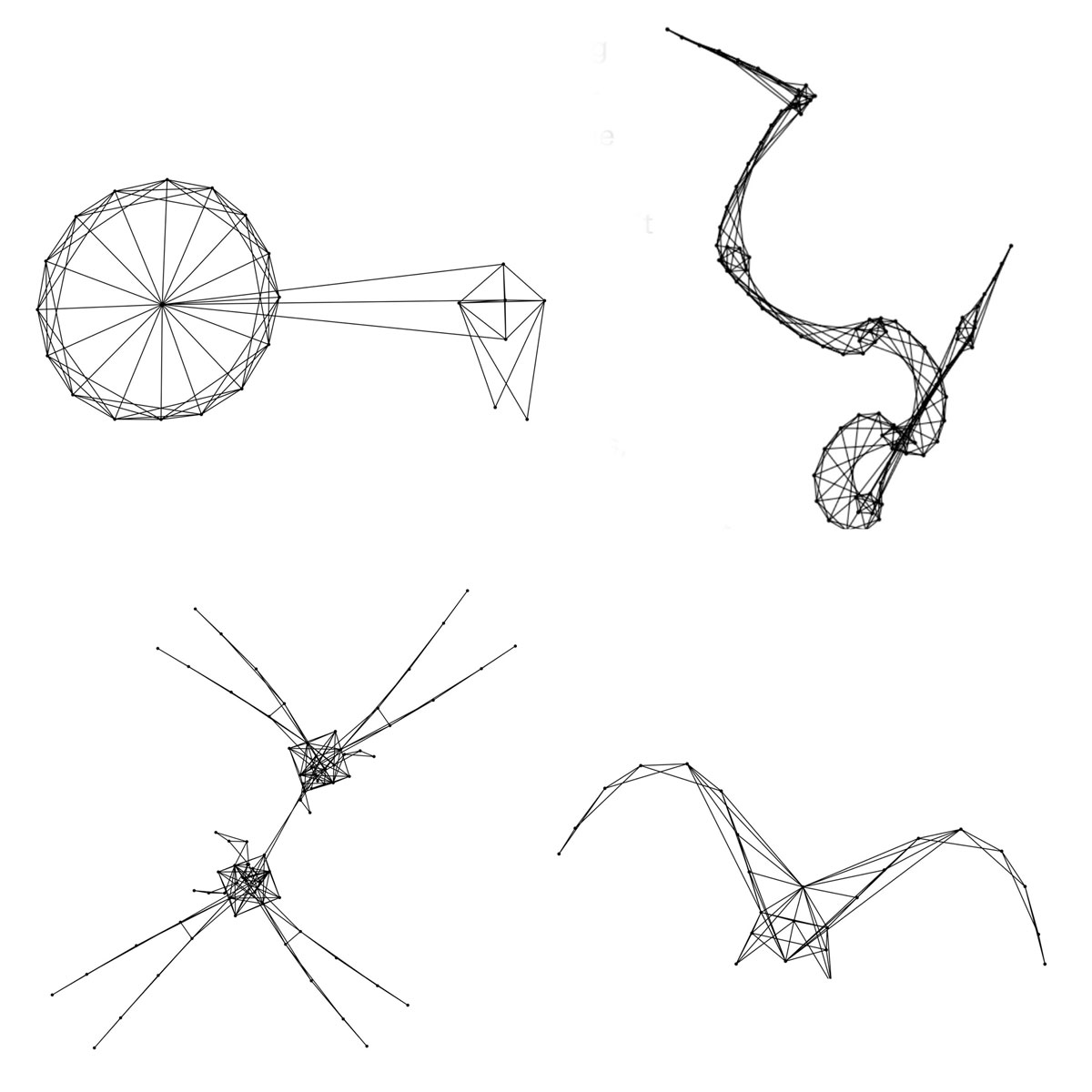

Another thing the users have been able to do that took a lot of conscious effort is to develop models that fly. I really didn’t expect that. They’ve made models that effectively defy the gravity built into the system. This is an example of the community going through a process of experimentation and creating something and analyzing it and improving on it. They weren’t just revealing something I’d hidden in the software; they were genuinely discovering new potential I hadn’t even suspected.

It sounds quite Darwinian.

It is like evolution in many ways, but it’s missing some of the mechanisms that would allow it to be really called evolution. Most importantly, it lacks any competition for resources which evolution typically has. Perhaps that’s one reason why the sorts of things you see in the “sodazoo” are somewhat like what you see in the pre-Cambrian explosion in the earth’s fossil record. There’s this almost crazy diversity because there’s so little competition in the environment. Soda users think, “As long as it doesn’t fall down, it’s okay.”

One of the things that surprised you, I gather, is that some people turn out to be star constructors. Creatively speaking, it hasn’t been a level playing field.

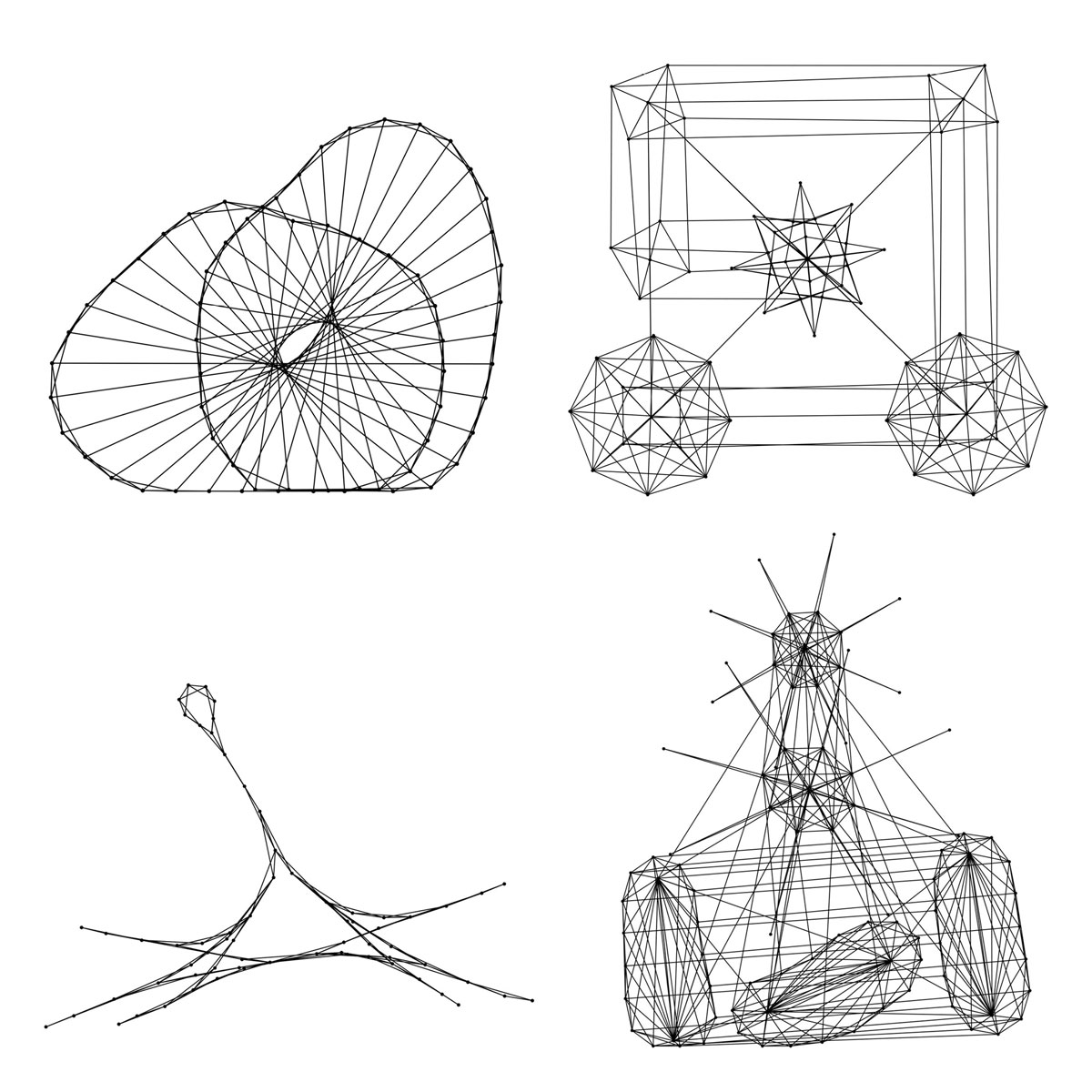

Yes. I had imagined everyone would be equally good, and that’s not the case. The first real breakthrough user who absolutely raised the bar of what we could expect to achieve was someone who called himself Kevino. A few months after the software became publicly known, he sent us twenty or so models, and all of them were a quantum leap forward in sophistication. The most memorable was one called Unfold. When you first saw it, it was just a triangle sitting on the bottom of the screen, but the triangle started to expand, and then it would suddenly scrunch like a pop-up and unfold into a multi-faceted construction. Then, rather remarkably, it could slowly contract in a very complex geometric way back into the simple triangle. It was a completely different genre and not anything to do with my preconceived idea of the program, which was basically just to enable things to move back and forth across the screen. Kevino had found a completely different style of movement, and it was executed with a great deal more skill than I’d imagined was possible.

One of my all- time favorites is another Kevino model called Shape-shifter. Again, when you first see it, it appears to be just two triangles joined together floating in space. Then those triangles unfold into an array of triangles, and then that unfolds again, and each time it unfolds it forms a different shape. That was extremely surprising to me because all the movements of sodaconstructor are driven by one sine wave, and so I always imagined the scope of the movement was going to be repetitive on the same timeframe as the wave, but Kevino was able to create something that had a larger scale of change and appeared almost random, despite the fact that the software is completely deterministic.

It turns out that users have very different and often quite idiosyncratic construction styles, which is also interesting given the mechanistic nature of the system.

Yes, the building blocks are so primitive that it’s surprising that people could put so much personal voice into it. Every so often someone comes along with a new break-through style that is picked up by others. A memorable character in that respect was a user named Mono. All we really know about him is that he lived in Japan. He is particularly known for introducing a style of construction that has since been called flex-chains or flex-loops, characterized by models made up of long chains of closely spaced masses. He designed all these remarkable models and then disappeared. Other users have since picked up on this style, but it remains recognizably his. Kevino has done some beautiful models using these chains, including one called Buggerfly and another one called Love—both of which have a really organic quality to their motion.

Looking at the evolution of the soda universe and seeing how the models have progressed from very simple to ever more complex, do you think there is a lesson here for understanding the development of life on earth?

It’s a difficult issue, because everything in the sodazoo has been designed by humans. In that respect it’s more like creationism in that there are always conscious agents behind it. That makes it difficult to take away lessons applicable to nature, other than the idea that there is some driving force towards diversity rather than pure homogenity—it’s like an ecosystem that doesn’t work unless it has diversity. Novelty or originality is one of the main drivers, and that’s maybe a lesson both in sodaconstructor and nature: diversity is good.

I gather there have been discussions in your user forums about the issue of creationism versus evolution.

Yes, there are a number of people playing with the software who are strongly advocating a creationist account of life. Maybe rather naively, I imagined that doing a project like this would somehow close down the debate. But people point to it as evidence of the need for there to be a conscious agent behind creation, and it was a surprise to me that the project was able to support such a diverging debate.

In part this is supposed to be an educational tool. What specifically do people learn here?

Sodaconstructor has a good deal of Newtonian mechanics built into it. But perhaps the more interesting thing that can be learned is the more transferable skill of how it’s possible to create or invent through a process of trial and error. In terms of pedagogy, we’re building on the idea of learning through a constructivist style, seeing knowledge as something that people have to actively build in their own heads, and that building artifacts can be a good way of building knowledge.

In sodaconstructor, if the first thing you construct is a square and you press “simulate,” it’s probably going to fall flat on the ground. But as long as you don’t find that too disheartening, hopefully the next thing you’ll think of is drawing a cross within that square to cross-brace it. Then if you press “simulate” perhaps you’ll get a square that will bounce and spring back upright and remain square. That’s perhaps what we’re most interested in facilitating—getting the user to have a genuine moment of discovery. That’s only possible if the software has a sufficient degree of openness, which also has to be enough to allow for failure.

You have created this world, but you’re not really the master of it.

These days I’m almost embarrassed to reveal the models I made myself because they look distinctly juvenile compared to some of the later models by others. I haven’t really tried to keep up with the great model builders like Mono and Kevino. It was evident I wasn’t going to be able to, and it was actually more fulfilling just to let them develop their own art and take it much further than I was able to.

Do you see this as a process that will keep on going, with the models getting ever more complex? Or will it plateau out?

If you’d asked me that three years ago, I’d have said yes, but it hasn’t. The users keep developing new things. They are very good at exploiting any bugs in the system and making technologies I hadn’t thought were possible. Our aspiration now is to try to see if we can produce a system where the users can modify the software itself. This is now a major project for sodaplay; to make the software mutable and let the users start to tinker around with the instructions and see where that takes them.

It’s like you’re allowing them to genetically engineer the code itself.

Yes, it allows our users the agency to realize their best ideas. We have quite an active forum in which they talk to each other, and often they’ll have ideas they can’t realize, like, “Wouldn’t it be interesting if the masses had magnetic polarity so we could make models that attract and repel each other.” At the moment when someone has a great idea like that, people can talk about it, but there isn’t any mechanism by which they can realize it and start experimenting with it. That’s precisely what we’re trying to do in the future.

In some sense you are the god of this universe. You have created a cosmos and the users are angels bringing various orders and suborders of creatures into being. It must be fascinating to watch what they do with it.

One of the things I’m working hard to do is to dethrone myself. I am a little uncomfortable with some of the almost reverence that’s apparent in the forums. In a way, I become almost like a mythical character—people whisper as to whether Ed exists. I’m much more eager to open it up to be a more creative ecology where anyone that has a good idea can realize it rather than me being in a privileged position of the sole creator.

For more models from Kevino, one of the most innovative sodaconstructors, see here.

Ed Burton is an artist and computer programmer and director of research and development at Soda Creative in London.

Margaret Wertheim is director of the Los Angeles-based Institute For Figuring, an organization devoted to enhancing the public understanding of figures and figuring techniques (www.theiff.org). Also a science writer, she pens the Quark Soup column for the LA Weekly, and is currently working on a book about the role of imagination in theoretical physics.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.