Rome, Broken City

Patching up the Eternal City in the Renaissance

Denise Bratton

For who can doubt that Rome would rise again instantly if she began to know herself.[1]

—Petrarch, letter to Giovanni Colonna

Sometime after his first visit to Rome in 1337, Petrarch conjured up the ruins of the ancient capital in a letter to his friend Giovanni Colonna, reminiscing about their walks through the “broken city,” where “the remnants of the ruins lay before our eyes.” Yet he never actually describes what they saw, instead reciting an imaginary itinerary of sites where key events in pagan and Christian history occurred. Prefiguring the central project of Renaissance humanism to collect and reassemble the remains of the past, Petrarch invoked the power of ruins to trigger collective memory, and his account uncannily echoes in Freud’s use of ancient Rome as an analogy to enter into “the more general problem of preservation in the sphere of the mind.”[2]

Petrarch’s strictly literary approach gave way nearly a century later to the aestheticizing optic of artists who began to systematically study, measure, and render the ruins of ancient architecture and sculpture in Rome. Early sketchbooks set the standard for a rich tradition of engraved and painted views in which the effects of fortune, time, and nature (not to mention human folly) became the “humanist” subtext for transforming the ruins into historical as well as artistic monuments in spite of their fragmentary condition. In fact, it was their very incompleteness that gave free play to the architectural imagination.

From the early fifteenth century, literary and visual discourses on Rome’s ruins were interlocked as rubble was refigured to visualize the historical gap between contemporary and ancient worlds. However, just as this period saw the rise of modern discourses on architecture and the city and a new awareness of ancient architecture as a form of cultural capital, debate raged among humanists who argued that the Roman Church was guilty of looting and demolishing antiquities in the name of conservation and reconstruction. In fact, as some buildings were dismantled to meet increasing demands for marble and others were neglected and fell into decay, collective forgetting outpaced collective memory.

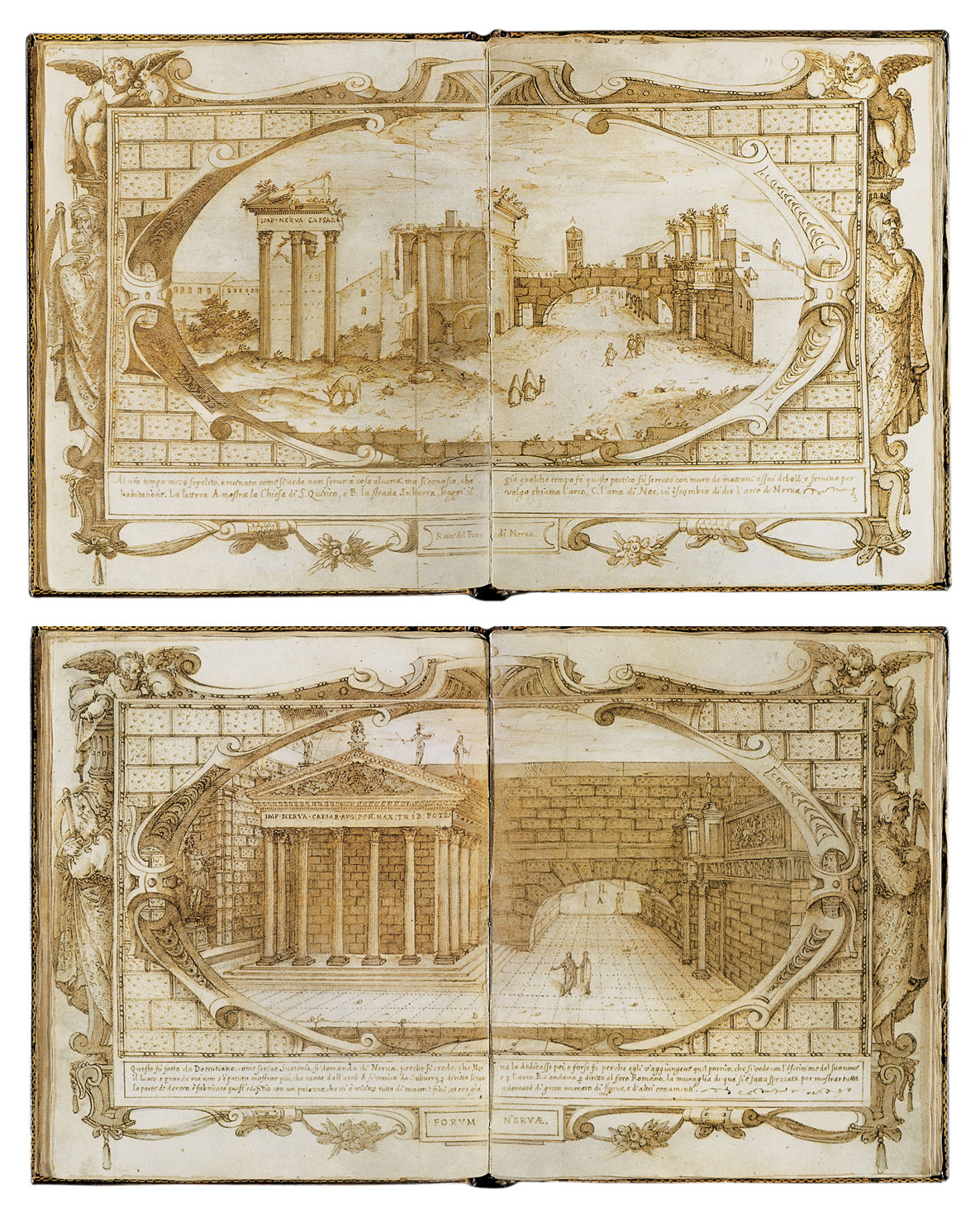

In the mid-sixteenth century, French topographer and engraver Étienne Du Perác or one of his followers produced a book of framed views of ruined Roman monuments paired with imaginative “reconstructions.” One of these pairs of drawings treats the Forum of Nerva, which was actually begun by Emperor Domitian (81–96 AD) and completed after his death by Nerva (96–98 AD). Also known as the Forum Transitorium, the long narrow enclosure originally functioned as a throughway conducting heavy traffic between the Forum Romanum along the old road known as the Argiletum. The rough peperino stone of the lateral walls was faced with smooth marble, and the interior was ornamented with a Corinthian colonnade supporting an ornate entablature.

Neither the sacred nature of Domitian’s Temple of Minerva nor the glory of the emperors themselves, or even the strikingly modern concept of a decorated street could prevent the forum’s decline. Only one pair of fluted columns known as Le colonnace survives today, the graceful arches at the end and the temple that Du Perác recorded in the sixteenth century having been dismantled by contractors operating illegally out of a “quarry” at the perimeter of the forum in the early seventeenth century.

Du Pérac’s reconstruction recalls the rationalized perspective space of Serlio’s design for a “tragic” stage set, dating from slightly earlier.[3] Reimagining the walls as rusticated, in keeping with sixteenth-century rather than ancient Roman taste, and interpreting Le colonnace as a column display rather than a fragment of the original colonnade, Du Pérac read the ruins for his own time. He stripped down the once-ornate forum and also massed it up, referencing not so much imperial Roman architecture as medieval fortresses, while at the same time adumbrating a new kind of urban space to accommodate idealized humanist statesmen — picturesquely dressed in togas — who embody the civic virtues of the time. Paired with this soberly theatrical reconstruction is a bucolic view of the site as it actually appeared to Du Pérac. Tiny figures establish the scale of the forum half-buried in debris, which by then had simply reverted to its early function as a connecting route. Here, the fragment of a nearly vanished architectural complex appears dwarfed by the great emptiness that surrounds it. Combining elements of Serlio’s “comic” and “satiric” set designs,[4] the informal and eclectic buildings that had taken hold around the forum look unkempt, weeds spring from the arch as well as the skeletal remains of the temple, and an animal grazes as if in a pasture.

In Du Pérac’s optic, the ruined forum, the residue of fallen empire, was effectively reinvented as the symbolic political space of an emerging state. However, in the intervening centuries, the ancient forum’s excavation and elevation to the status of a historic monument seems only to have invalidated it. A fate perhaps worse than oblivion or burial, thanks to the science (and politics) of archaeology, it has been embalmed and its urban function cancelled. Ironically, a recently proposed reconfiguration of the Roman fora as an “archaeological park” where circulation again becomes a priority may more closely approximate Du Pérac’s utopian—if theatrical—proposition.

- Petrarch’s letter is signed “30 November, in transit.” In Francesco Petrarca, Rerum familiarum Libri I–VIII, trans. Aldo S. Bernardo (Albany: SUNY Press, 1975), VI, 2, p. 190ff.

- Sigmund Freud, “Civilization and its Discontents” (1929–1930), trans. James Strachey, et alia, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1961), vol. XXI, pp. 69–70.

- See Sebastiano Serlio on Architecture, trans., intro., and commentary Vaughan Hart and Peter Hicks (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1996), vol. 1, Bk. 2, p. 89.

- Ibid., p. 87 and 91, for comic and satiric stage sets.

Denise Bratton is an art and architectural historian and editor based in Los Angeles. She consults on programs and publications for the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal, is a co-editor and one of the protagonists of Log: Observations on Architecture and the Contemporary City, a member of the editorial board of Architectural Design/AD Magazine in London, and also collaborates with the Border Institute in San Diego.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.