Armies of the Night

Satan’s fetus stalks the suburbs

Mark Dery

Something was moving. In the heat of a San Francisco night, in the summer of 1982, something was scuttling across the floor toward the foam-rubber mattress where I lay. It was moving fast enough to jolt me out of a dead sleep. Not only was this thing coming toward me with alarming rapidity, it was big. From my perspective—lying on my side on a floor mattress, practically at eye level with the intruder—it might have been a good-sized mouse ... if mice had six legs.

In a jump cut, I was out of bed, across the room, switching on the light to reveal a crawling horror: a humongous insect, thicker than a man’s thumb, maybe three inches in length. It had powerful, cricket-like hind legs and a caramel-colored abdomen, ringed with amber bands. Its head was dried-blood red, with the lacquered glossiness of a candied apple. It made me think of a skinned thumb, or the swollen head of an aroused penis, shiny with precum.

The creature was obscene in its ugliness. But what was it? David Cronenberg’s idea of a partial-birth abortion? A stool sample from the man-eating xenomorph in Alien? A nightcrawler from the cultural unconscious?

Sweeping the thing into a dustpan, I shuddered at its weight as I carried it to the bathroom. To my horror, the creature swam against the tide when I flushed, scrabbling frantically at the toilet bowl. I flushed. And flushed. And flushed. (Die, monster, die!) At last, it disappeared down the porcelain gullet. The toilet made a gagging sound.

Trembling with revulsion, I laid the heavy ceramic lid of the toilet tank across the closed seat to ensure that no six-legged freak could exact revenge, even if it did manage to clamber up, out of the sewer. Not that I slept much that night. In the dark, I could still see those beady black eyes staring back at me unblinkingly as I sent the abomination swirling into Eternity with a final flush.

• • •

Decades later, I found myself looking into those eyes again, when a Google search put a name to the face in my nightmares: the Jerusalem cricket (order Orthoptera, family Stenopelmatidae, genus Stenopelmatus)—a large, wingless relative of the grasshopper and the katydid that spends most of its life underground except at night, when it leaves its burrow to scavenge for food or seek out a mate.

Curiously, the Jerusalem cricket is neither from Jerusalem, nor is it, properly speaking, a cricket. (As Linda Richman used to say on Saturday Night Live: Discuss.) Most species live in the United States, west of the Rockies—specifically in California, a world away from Jerusalem. And its resemblance to its namesake, the cricket, is only passing: unlike the Gryllidae, the Jerusalem cricket doesn’t chirp, doesn’t hop, and the females of the genus don’t have long ovipositors like female crickets do. (To complicate matters, Stenopelmatus is also known, in those states where the sobriquet hasn’t already been claimed by the wood louse, as the potato bug. Predictably, it isn’t a true bug, nor is the potato a staple of its diet. Its typical fare is decaying plant matter and decomposing animals.)

As it happens, most of Stenopelmatus’s seemingly numberless species are also nameless because they’re all but impossible to tell apart, except by counting the spines on their hind legs. Identifying and naming the species of Stenopelmatus is a Herculean labor, made even more daunting by virtue of the fact that the scientist who has set himself this task, David Weissman, confronts it alone, in his spare time (entomology is his avocation; in his working life, he’s an anesthesiologist). He is the world’s foremost authority on JCs, as he jocularly calls them, because he’s the only entomologist who has devoted himself to studying the genus.

Based in the San Francisco Bay Area town of Los Gatos, Weissman has identified forty-three new species in California alone, where JCs seem to be everywhere: in mountains, chaparral-covered foothills, oak woodlands, riparian belts, desert dunes, coastal sage scrub, and, increasingly, the homes of horrified suburbanites.

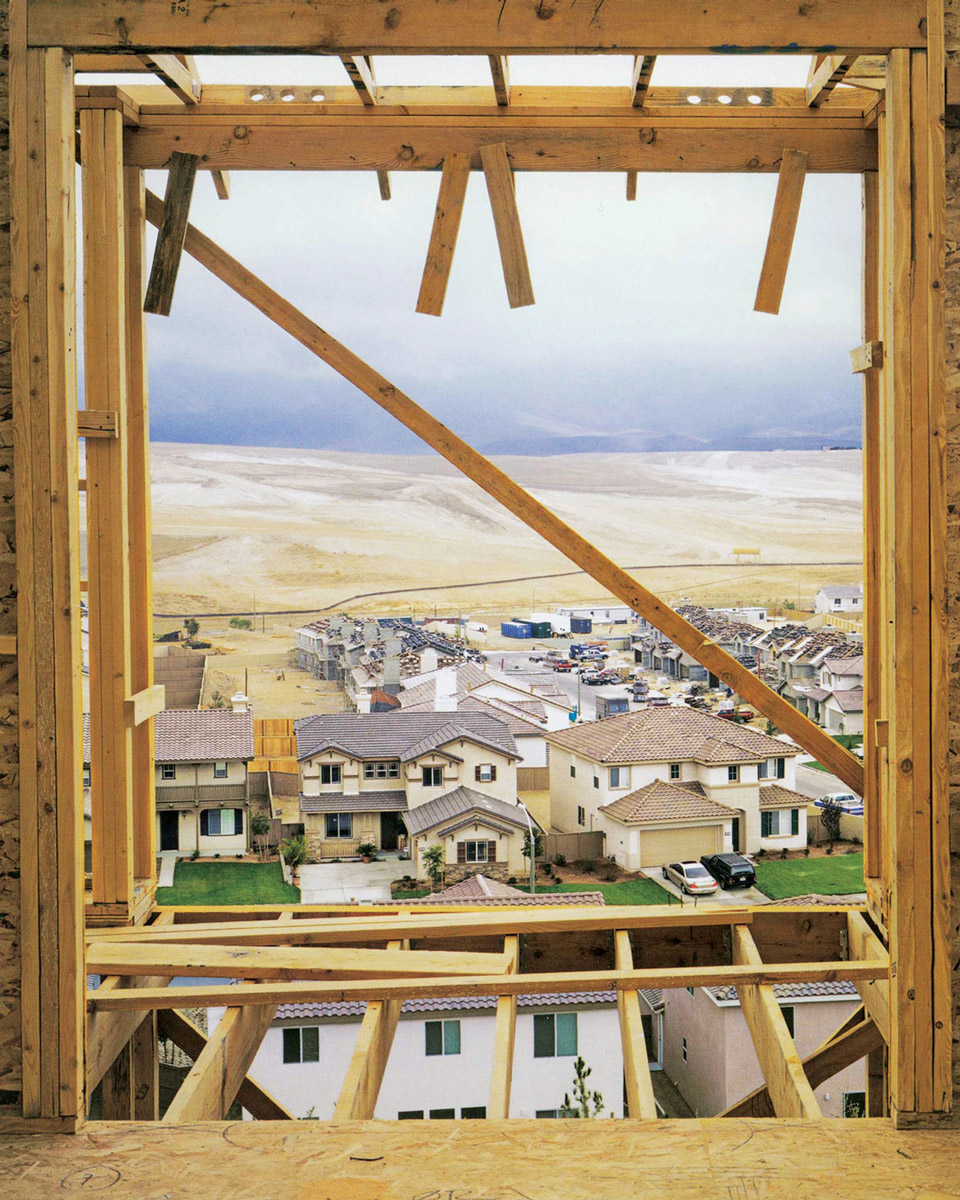

As sprawl creeps eastward into what was once wild, more and more Californians are coming face to face with JCs. As Mike Davis recounts in Ecology of Fear, developers, their pro-growth political beneficiaries, and what Davis calls “a regional planning system dominated and corrupted by development interests,” have collaborated for generations on the chainsaw massacre of the state’s wild places.[1] “Entire Southern California ecosystems, including salt marshes, native grasslands, Engelmann oak savannas, and vernal pool communities, have become virtually extinct over the past century and a half,” he notes.[2] Even so, the subdivision of Eden continues, paving the way (literally) for more McMansions, more malls, more freeway arteries.

As white-flight exurbanites stake their claims at the wild edge of eastern California’s chaparral-covered foothills, they’re confronting a border of another sort, trespassed by a new breed of alien. The border, in this case, is the “ecotone”—ecologists’ term for those transitional spaces where biological communities such as forest and prairie, or in this case lawn and chaparral, intersect and interact. The increase in confrontations between exurban homesteaders and large predators is evidence that hostilities between culture and nature are escalating. In news reports of coyotes adapting to a suburb-friendly diet of garbage, pets, and unattended toddlers, or of cougars attacking humans on the wrong side of the white-picket divide between manicured lawn and backcountry scrub, environmentalists hear the annunciatory trumpets of an ecological Judgment Day.

Despite their low media profile, Jerusalem crickets are emissaries from a world out of balance, too—sentinel species whose increasingly frequent run-ins with exurbanites are symptomatic of habitat destruction. “In Jerusalem crickets, you have so many species that are geographically limited to a sand dune, to a mountain peak, that if you develop that habitat you may cause a species to go extinct because it’s only found in a very limited area,” says Weissman. No one knows how many species of Stenopelmatus are dangling from the rim of extinction, he says, because he’s the only one studying the insect. “I’m trying ... to document as many of these different species as I can, to show that they’re geographically limited,” he says, “and then I’ll try to get some of these habitats protected. Until I give them a name, we have no formal mechanism to do that.” There’s an Adamic loneliness to Weissman’s one-man quest to name every branch of the JC tree and record it in the Book of Life. Yet there’s a whiff of the apocalyptic about it, too: Bruce Dern as the hairy-eyed tree hugger in Silent Running, single-handedly defying myopic politicians in order to save what remains of Earth’s ecosystems.

• • •

Decades after the fact, I discovered that my late-night encounter with Stenopelmatus was far from unique. In all of its particulars, my experience was struck from the same mold as many of the first-person accounts archived on the tongue-in-cheek website, PotatoBugs.com (“dedicated to the fabrication and perpetuation of fear, hate, and disgust for the Potato Bug”).

Time and again, the victims of stenopelmatid abuse sharing their recovered memories on PotatoBugs.com play variations on the themes I touched on, in my account of the Thing in the Moonlight. There is the same shock and awe at its unexpected weight (it’s the heaviest insect in California, according to Weissman, who has recorded specimens weighing 13 grams, more than some mice), the same revulsion at the sheer size of the beast:

While trying to decide what this monster-looking thing was, my husband informed me that it was a Potato BUG. No way, bugs do not come in a size large enough to wear a dog collar; yes it was that big. The size of a miniature dog of some kind. Now, my husband says that terror has a way of making me exaggerate but I stand by what I say I saw.[3](For the record, Weissman has never encountered a specimen larger than three-and-a-half inches.)

There is the same panicked attempt to flush the beast into oblivion, the same crazed fear that it will rise again to exact a vengeance too monstrous to mention:

Called my son downstairs to handle the beast, he tossed it into the toilet and before the flush I swear that thing was swimming, ended up doing the backstroke as it went down. And eewww all I could think of all nite was that it could come back up. Now every little noise at nite in the dark house makes me think I’m living with a whole nest in my house![4]Lastly, there is the same post-traumatic fallout, the mind-curdling memories that users insist have “scarred” them for life, condemning them to nightmares crawling with orthopteran horrors: “I have come here to post my story in hopes that I will slowly heal from my traumatizing encounter with the hideous creature known to all as the potato bug.”[5]

• • •

But seriously: how does a largely subterranean, mostly nocturnal insect that poses no threat to humans become what PotatoBugs.com calls “the most universally feared, hated, and disgusting [creature] on the planet?” Despite its lowly but important role in Californian ecosystems (JCs are protein bars for predators) and its relative harmlessness (JCs can inflict a painful bite but typically do so only when provoked and, contrary to popular belief, are not poisonous), the Jerusalem cricket is for many Californians the poster child for fear and loathing. It inspires a revulsion that channels cultural anxieties and Freudian fears, not to mention our primordial antipathy toward The Insect, the blank-eyed face of nature at its most inhuman.

“The single most disgusting creature known to man. Its tiny little head staring right at me, its mandibles on my bare skin”: in the ironic support group now in session on PotatoBugs.com, the word disgust is a mantra.[6] But what, exactly, makes the Jerusalem cricket so disgusting? Let us count the ways: there are the dead, doll eyes, set in a bald head that is nauseatingly glossy, like a Tootsie Pop that somebody has been sucking on. Creepier still, Stenopelmatus is loathsome to the touch, unexpectedly fleshy for a creature with an exoskeleton: “When I picked it up (behind the head) I almost dropped it on instinct because it felt so vile: overfilled and soft, like a water balloon,” writes a user named Bitriot, on the website Everything2.com.[7]

Yet, while undeniably rooted in the biological and inescapably visceral in nature, our disgust for the cricket is more than merely visceral. “Like all emotions, disgust is more than just a feeling,” William Ian Miller reminds us in The Anatomy of Disgust:

Emotions are feelings linked to ways of talking about those feelings, to social and cultural paradigms that make sense of those feelings by giving us a basis for knowing when they are properly felt and properly displayed. Emotions, even the most visceral, are richly social, cultural, and linguistic phenomena. … Disgust is a feeling about something and in response to something, not just raw unattached feeling.[8]Disgust inclines toward moral judgment, he argues, inviting us to equate the foul with the fallen, defilement with depravity. Thus the reflexive linkage, in many PotatoBugs.com posts, of visceral recoil with moral reproach. The word evil thumps out a steady backbeat in the site’s discussion threads. JCs are evil because they live underground, the realm of the chthonic, and, like all unhallowed things, they only come out at night. They’re the untouchables of the insect world, battening on death and decay. Most of all, though, they’re evil because they’re ugly—disgustingly ugly.

Yet, in the mass imagination, the Jerusalem cricket is more than merely evil; it is uncanny. The insect’s folk names—niña de la tierra and cara de niño (Spanish for “child of the earth” and “child’s face,” respectively), wó see ts’inii (Navajo for “skull insect”) and, more recently, Satan’s fetus—hint at the psychological roots of its effect on us. In his inexhaustible essay, “The Uncanny,” Freud cites Ernst Jentsch’s theory that what makes the uncanny so disquieting is that it destabilizes the either/or logic of our culture, perverts the philosophical binaries that structure the Western worldview: inanimate/animate, organic/mechanical, and so forth.[9] Uncanny things are border-crossers.

As Satan’s fetus and other such names suggest, the bald, bulbous-headed insect’s uncanniness has much to do with its humanoid appearance, specifically its disconcerting resemblance to a human baby—a resemblance enhanced by the widespread belief that stenopelmatids can cry like babies. (Not true, although they can produce a squeaking, called stridulation, by rubbing their hind legs against their abdomens.) JCs stand at the uncanny intersection of cute and eeeeeyewwwww. They put a face, at once cuddly and repugnant, on Daniel Harris’s argument in Cute, Quaint, Hungry and Romantic: The Aesthetics of Consumerism:

Cuteness is not an aesthetic in the ordinary sense of the word and must be by no means mistaken for the physically appealing, the attractive. In fact, it is closely linked to the grotesque, the malformed. ... The grotesque is cute because the grotesque is pitiable, and pity is the primary emotion of this seductive and manipulative aesthetic that arouses our sympathies by creating anatomical pariahs, like Cabbage Patch Dolls. ... Something becomes cute not necessarily because of a quality it has but because of a quality it lacks, a certain neediness and inability to stand alone, as if it were an indigent starveling, lonely and rejected because of a hideousness we find more touching than unsightly.[10]

Speaking for the vocal minority on PotatoBugs.com who find Stenopelmatus cute, a user named Wyldbrry argues Harris’s point:

Two months ago ... I saw a potato bug for the first time. ... When I saw him I stumbled back in fear. But my curiosity got the best of me and I came forward and stared into his beady eyes. He must have slapped some kind of mind control mojo on me ‘cause my next thought was, “aw poor little fella, he’s kinda cute in an ugly sort of way.” [11]Not only are JCs uncanny, but like all insects they’re irrevocably alien; maybe even more so than most members of class Insecta . Californians marvel, for example, at the bizarre sight of JCs marching lemming-like into ponds or pools. Inevitably, the insects drown, at which point a wriggling, whip-like thing—the parasitic horsehair worm (Gordius robustus or Paragordius varius)—bursts forth (out of the insect’s anus, if you must know), swimming off in search of a mate and leaving its host to die. According to Weissman, JCs ingest the worm when eating “dead material.” The worm takes up residence in the insect’s gut, where it hatches, after which it “cleans out the Jerusalem cricket, eats its internal organs.” All the while, the host animal behaves like any normal JC, blithely unconcerned that it’s being gnawed hollow. When the time is right, the worm releases hormones that inspire the insect’s irresistible compulsion to drown itself. This sort of parasitism is common enough among insects; from an anthropocentric perspective, though, it looks unspeakably alien.

The cricket’s alien nature—alien from a human’s-eye view, at least—trips the wires of our species-centric xenophobia. “There is nothing man fears more than the touch of the unknown,” said Elias Canetti, to which we might add: whether it’s nature or culture.[12] Most Californians’ chain of unreasoning, upon encountering Stenopelmatus for the first time, goes something like:

A. What is it? I’ve never seen anything like it.

B. It’s weird. And ugly. Disgustingly ugly. Evil ugly.

C. Must kill it, kill it dead before it contaminates my world.

“People write to me and say, ‘Gee, I saw this thing; I smashed it; I poured lighter fluid on it and lit it—would you like it?’” says Weissman. “People have this extreme reaction.” JCs arouse our fear of nature, a cultural neurosis that is, at its roots, a pathological fear of all that is Other. In the popular unconscious, stenopelmatids stand in not only for the Wild but for the illegal alien, who emerges at night to tunnel under la linea, the wall of steel.

• • •

—M. Night Shyamalan, The Village[13]

On landuse and planning maps, of course, the division between “developed” and “undeveloped” areas is drawn as a straight-edged border. Spuriously precise boundaries likewise define parks, wildlife refuges, national forests, and official wilderness areas. In reality, there is an infinitely more intricate interpenetration of the wild and the urban. ... Coyotes and cougars ... are unwelcome heralds of a breakdown in the clear-cut, impermeable, but essentially imaginary boundary between the human and the wild.

—Mike Davis, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster[14]

In M. Night Shyamalan’s movie The Village, a group of middle-class whites, post-traumatically stressed by the Senseless Violence of Our Times, build their own private Idaho—actually, a cruelty-free Colonial Williamsburg, hidden from the modern world by a wild wood on loan from the Brothers Grimm.[15]

The only downside to this Fantasy Island for Real Simple readers is the ever-present menace of Those We Do Not Speak Of: hulking, hairy creatures who patrol the borders of the dark and trackless wood. Of course, borders are made to be breached: the village idiot sneaks into the Forbidden Woods, and the monsters from the wrong side of the tracks—er, trees—go wilding through the all-white village, leaving mutilated house pets as their calling cards.[16]

Sure, the movie is a big, fat tub of Jolly Time® Blast O Butter® Popcorn for the mind. Still, Shyamalan’s bogeymen have a message for us: the age of tidy dualisms is well and truly over; in the chaos and complexity of our times, sharp distinctions are a philosophical mirage. White-flight exurbanites may circle the wagons, in gated communities, against gangbangers and border-crossers, and nativist demagogues may demand a ring of steel around Fortress America—a levee against the flood of immigrants threatening, in the immortal words of Dr. Strangelove’s General Jack D. Ripper, “to sap and impurify all of our precious bodily fluids.” But whatever we repress always comes back to bite us, whether it be the race-based inequities that breed Bloods and Crips, or the economic dealmaking that turns a blind eye on illegal immigration, or our centuries-old policy of eradicating whatever wild nature we can’t domesticate.

That’s why Shyamalan’s villagers are forever and always speaking of Those We Do Not Speak Of. And that’s why there’s a low-lying fear in California’s sprawl country, an anxiety that occasionally blossoms into collective panic attacks. Out where the McMansions meet California’s wild edge, white exurbanites’ worries assume mythic form. In the dark chaparral beyond the last street light, nebulous fears—of inner-city pathologies and the Browning of America and feral nature closing in—take palpable shape: pet-killing coyotes, cougars with a taste for birdwatchers and bikers, alien invaders from south of the border, Jerusalem crickets on the march.[17]

To connoisseurs of California absurdism, the stealthy penetration of suburbia’s perimeter by small swarthy aliens on the prowl after dark sounds suspiciously familiar. In the cultural firefight over illegal immigration, defenders of our declining empire conjure visions of a Brown Peril, overrunning the border like some biblical plague. On the hairy-eyed nativist fringe, cockroach is a well-worn term of opprobrium, as in blog comments like: “Here in California, the Mexicans are breeding like cockroaches...it might sound racist, but its [sic] true. Their culture revolves around filth and corruption.”[18]

In typical Trickster fashion, Chicanos have appropriated the slur and used it as a stick to beat the devil, as in The Revolt of the Cockroach People, Oscar Zeta Acosta’s novel about the Brown Power movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Or La Cucaracha, Lalo Alcaraz’s stingingly funny comic strip about pochos (Spanglish-speaking Mexican-Americans, caught in the double consciousness of their parents’ Mexican traditions and the Gringolandia in which they grew up). Or this ha-ha-only-serious post on the blog Corrente:

Principles of cockroach people:1. Avoid the Man. If the light shines on you, scatter.

2. Survive. Some of you will be stomped and gassed. Make sure the rest survive.

3. Don’t believe what you hear or read. Promises are just words.

4. There are more of you than there are of them who would destroy you.

5. Very few people like cockroaches. Beware of those who claim they do.

6. Gather what you need to survive.

7. The cockroaches have survived every attempt to eradicate them; they will prevail.

8. When the chance comes, move in a mass to secure food and territory.

In a sense, we are all cockroach people, pests, vermin, the sworn enemies of the bugman and his exterminators.[19]

At a time when camo-clad vigilantes patrol the US-Mexico border and cazamigrantes (migrant hunters) have declared open season on illegal aliens, tales of suburbanites terrorized by vermin resembling giant cucarachas can’t help but sound like social satire.[20] For Californians living in the free-fire borderlands, stumbling on a big, brown insect creeping surreptitiously through their homes is just one more Close Encounter with the Darker Other.

- Mike Davis, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster (New York: Vintage Books, 1999), p. 85. For a blow-by-blow account of how California developers and their political allies managed to pave paradise, see another chapter in Ecology of Fear, “How Eden Lost Its Garden.”

- Ibid., p. 205.

- Rhonda, “My Siting” [sic], www.potatobugs.com/dcforum/DCForumID2/369.html. Note: I have tried to maintain the idiosyncratic style of all posts quoted, which in some cases has meant leaving misspellings, grammatical errors, and arbitrary punctuation intact. However, I have corrected typos and cleaned up grammar wherever doing so didn’t significantly alter a writer’s voice. Also, in those instances where a writer’s malapropism makes his or her meaning unclear, I have taken the liberty of substituting the word the writer obviously intended.

- Christine in Ontario, CA, “RE: Potato Bugs in the Laundry,” www.potatobugs.com/dcforum/DCForumID2/149.html#1.

- Pollyesprit, “Scariest Bug of them all!!!,” www.potatobugs.com/dcforum/DCForumID2/169.html.

- From the “Share your Potato Bug stories” discussion topic, PotatoBugs.com, www.potatobugs.com/cgi-bin/dcforum/dcboard.cgi?az=list&forum=DCForumID2&conf=DCConfID2 [link defunct—Eds.]. Italics mine.

- Bitriot, www.everything2.com/index.pl?node_id=1071424.

- William Ian Miller, The Anatomy of Disgust (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1997), p. 8.

- See Sigmund Freud, “The Uncanny,” in The Uncanny (New York: Penguin Books, 2003).

- Daniel Harris, Quaint, Hungry and Romantic: The Aesthetics of Consumerism (New York: Basic Books, 2000), pp. 3–4.

- Wyldbrry@aol.com, “RE: Insect Armageddon happening in our home!,” www.potatobugs.com/dcforum/DCForumID2/145.html.

- Quoted in Sue Hubbell, Broadsides from the Other Orders: A Book of Bugs (New York: Random House, 1993), p. 157.

- From “Quotes” page of the official website for The Village, www.mnight.com/village/quotes [link defunct—Eds.].

- Davis, op. cit., pp. 204, 207–8.

- The colonists are trying to time-warp back to 1897 but seem to have missed their target date by about a century. For example, they affect a contraction-challenged pilgrimspeak that will be instantly familiar to anyone who has suffered through a grade-school Thanksgiving play.

- Do I overplay the race card? Consider this thumbs-up review of Shyamalan’s movie, from a user named Merlin posting on the white-supremacist website Stormfront.org: “The Village is entirely White [sic]. ... The idyllic image of the village (before the twist is revealed) was beautifully portrayed, and just seemed ‘right’ to me. I kept waiting for some black guy to appear and wreck the movie, but thankfully it didn’t happen. The audience was also mostly White, and an older crowd, so as you can guess it was wonderfully quiet. I only noted a few non-whites in the whole theater.” (Merlin, “RE: The Village,” Stormfront.org, stormfront.org/forum/t145848 [link defunct—Eds.]. Oddly, the fact that this white-supremacist utopia was dreamed up by an Indian-American, a member of the hated “mud” races, doesn’t seem to trouble the movie reviewers on Stormfront.org. As a member named Harry charitably allows, Shyamalan “is a pretty well assimilated mud, having been educated in Catholic schools and such. That doesn’t make him White, but it does keep him from making the BS anti-White films his kind usually create.” (Harry, “RE: The Village,” Stormfront.org).

- The “browning of America” is a phrase coined by the cultural critic Richard Rodriguez in his book Brown: The Last Discovery of America (New York: Viking Press, 2002).

- Posted by danthrax in the comment thread for “Mexicans Hate Black People” on ByronCrawford.com: The Mindset of a Champion. See www.byroncrawford.com/2006/04/mexicans_hate_b.html [link defunct—Eds.] For a fascinating analysis of the insect trope in hate speech, see Christopher Hollingsworth, “The Force of the Entomological Other: Insects as Instruments of Intolerant Thought and Oppressive Action” in Eric C. Brown, ed., Insect Poetics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), pp. 262–277.

- RDF, “More on Cockroaches and Vermin,” Corrente, www.pkblogs.com/corrente/2005/08/more-on-cockroaches-and-vermin.html [link defunct—Eds.].

- See R. M. Arrieta, “Armed & Dangerous: Vigilantes terrorize migrants crossing the border,” In These Times, 27 January 2003, www.inthesetimes.com/site/main/article/armed_dangerous/ [link defunct—Eds.].

Mark Dery is a cultural critic. The author of Escape Velocity: Cyberculture at the End of the Century (Grove Press, 1997) and The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink (Grove Press, 1999), he is at work on Don Henley Must Die, a series of essays on the cultural psyche of Southern California, specifically the badlands and borderlands of San Diego, where he grew up. He teaches at New York University in the Department of Journalism.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.