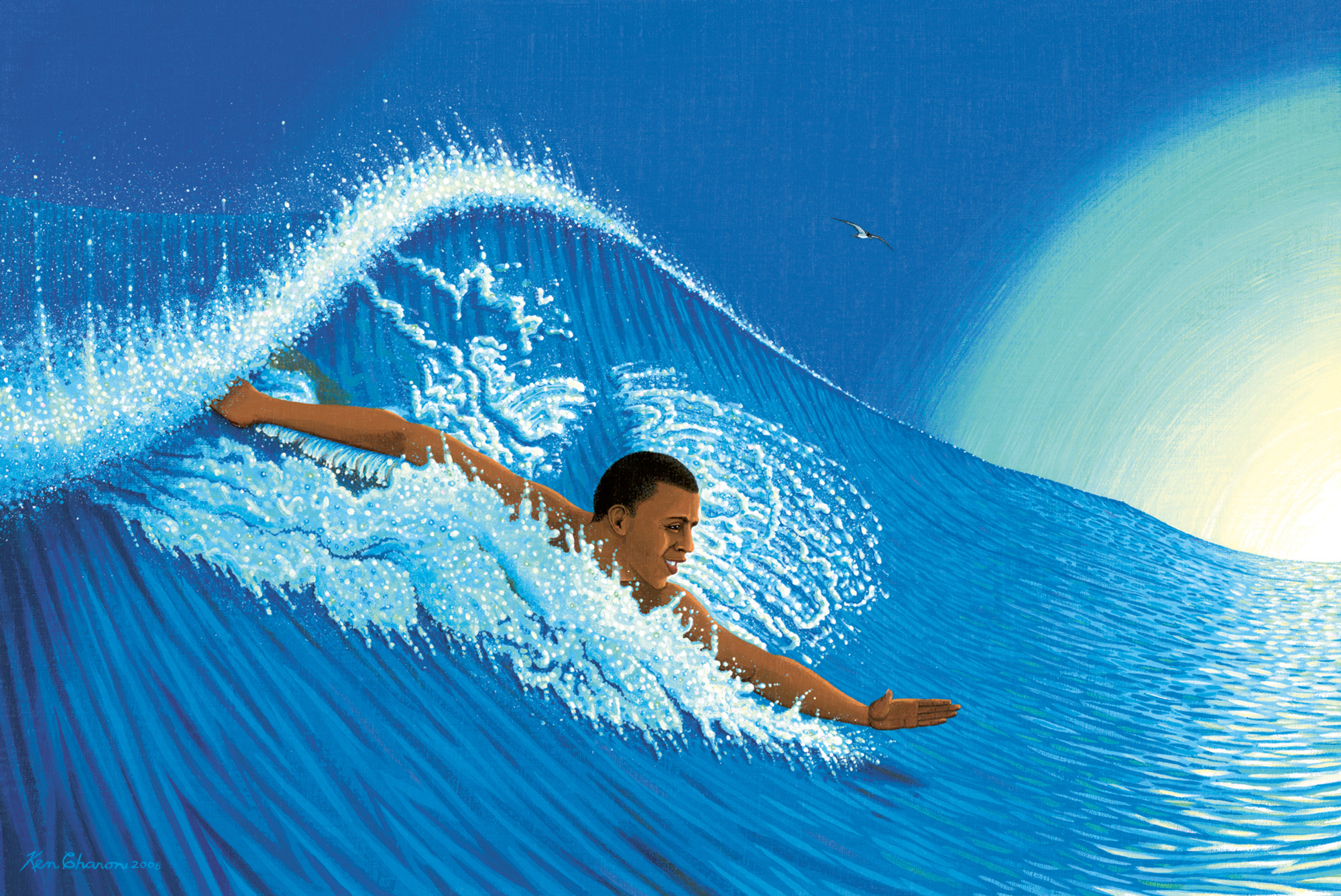

Being the Wave

Bodies and breakers at the seaside

Stefan Helmreich

During the American presidential election of 2008, close watchers of the news learned that Barack Obama was a bodysurfer, riding waves without aid of a board, propelled only by arms and swim-finned feet. The aim of the sport, writes enthusiast Robert Gardner, “is to cut diagonally across the face of the wave, trying to slide along just under the breaking curl. This increases the speed of the ride.”[1] Bodysurfing lacks the glamour of board surfing, or anything like its promotional industry. It is a solitary and spare enterprise, requiring a feel for how to launch one’s body across the arc of a breaking wave. Obama arrived at the activity biographically, growing up as he did in Hawai‘i. A first-generation African American, Obama was not, like his University-of-Hawai‘i-anthropology-graduate-student mother, Ann Dunham, a haole—a Native Hawaiian term that refers to white people from the mainland. He stood apart, too, from Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino immigrant communities as well as from Native Hawaiians—though Obama joked in Dreams from My Father that his white grandfather would sometimes describe him to sideways-looking white tourists as the great-grandson of King Kamehameha.[2] Obama cut a unique figure in the water, especially since so much mainland American history—think segregated beaches—has worked against African American recreational swimming.

This figure of Obama-in-motion impels my meditation here on bodysurfing, which asks how a politics might be read from the kinetics of the sport, from bodily aspirations that, these days, have bodysurfers wanting to “be the wave.” Drawing on an ethnographic account of a 2012 competition in California that I entered, I contend that embodied aquatic techniques—wet and fleshly phenomenological and political performances—shape not only bodysurfing bodies and selves, but also what bodysurfers take a wave to be.

What does it take to “be the wave”? It takes work, getting a feel for the curve of seawater, studying the methods of other swimmers, navigating social worlds surrounding beach and breakers. Cultural studies of surfing have mapped such navigations, tracking how the aesthetics of the sublime—of individual union with scary phenomena—have contoured risk-taking leisure.[3] Krista Comer, in Surfer Girls in the New World Order, reports on how women have struggled against their sidelining in surf culture, as successive genres of surfer masculinity—strapping, slacking—have claimed social space.[4] Racial politics have shaped the sport too. Comer tells the tale of Native Hawaiian surfer Eddie Aikau, who traveled to apartheid-era South Africa with haoles (who, like him, had been inspired by the 1966 movie The Endless Summer), only to be turned away from a segregated hotel—an affront his white friends did nothing to address, and which then racialized existing ethnic divides when the group returned to Hawai‘i. Arun Saldanha documents how shore-side tourism in Goa, India, ripples with race. His Psychedelic White proposes that racial identities materialize not through the enforcement of rigid boundaries, but rather through