Oneirocritica Afro-Americana

Dreaming of lucky numbers

Christopher W. Vandegrift

Popular in Europe since antiquity, books of dream interpretation—commonly referred to as dream dictionaries or, more simply, dream books—were first published in the United States in the latter half of the eighteenth century. Initially indistinguishable from those published contemporaneously in Great Britain, American dream books came into their own during the early to mid-nineteenth century, when publishers of cheap literature began selling dream books that catered to players of policy, an illegal lottery game then sweeping Northeastern cities.[1]

In policy, twelve strips of paper were drawn at random from a container, often a wheel, that held slips numbered from one to seventy-eight. Players were free to bet any amount on specific numbers, and the most common play, known as a “gig,” wagered that a combination of three different numbers would be drawn in any order.[2] Bets were taken by “brokers,” who operated under-the-table policy shops in cigar stores and other front establishments. The brokers, in turn, reported to policy “kings”—also known as “bankers”—who arranged and often rigged the drawings in their territory.[3] Rules for play and the payouts associated with different bets were explained on so-called rate cards, small handouts printed and distributed by each banker’s organization.[4]

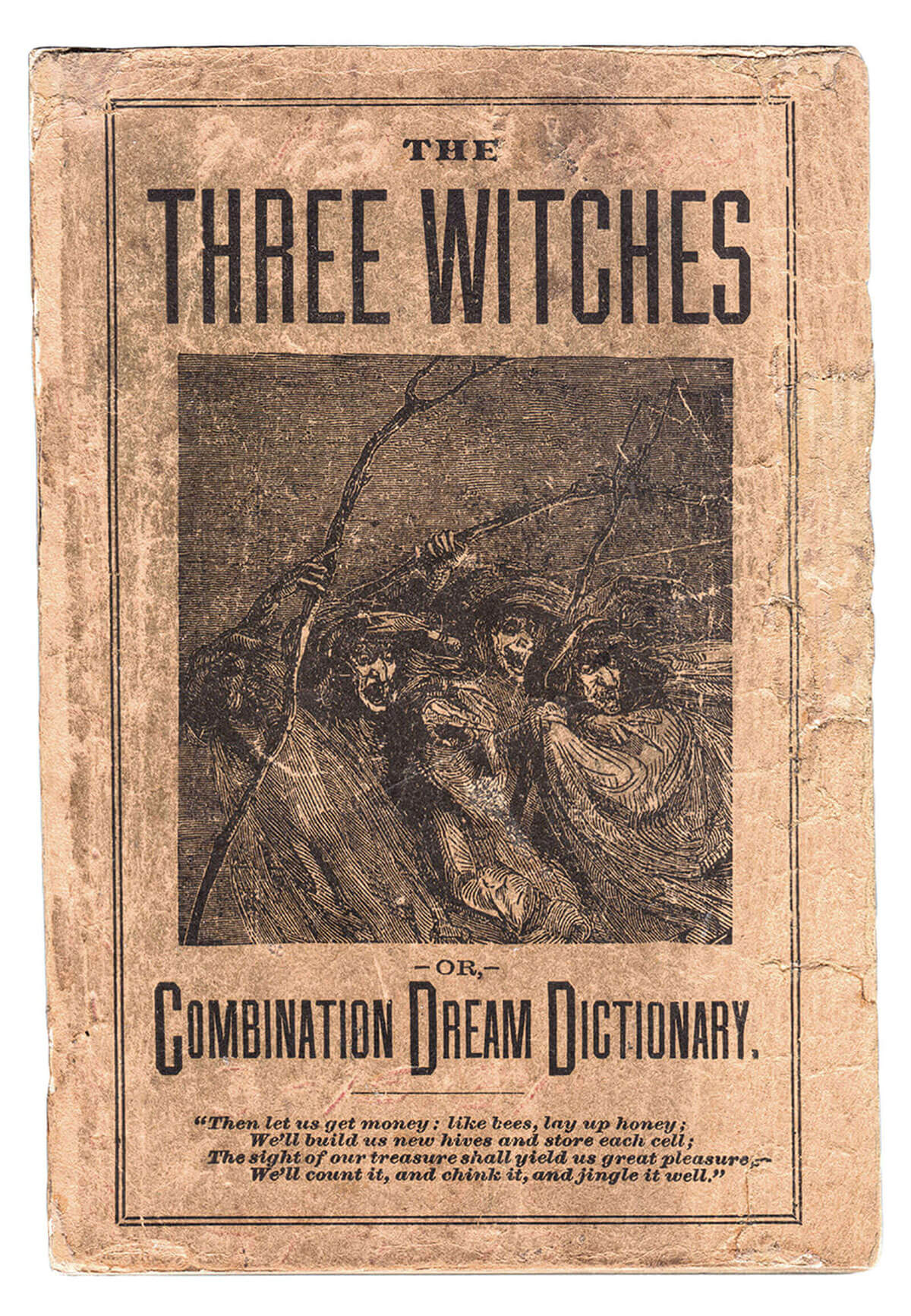

Ironically, the policy boom of the 1800s resulted in part from campaigns against the vice of gambling, which accomplished the gradual abolition of legally sanctioned lotteries across the United States. In the absence of lawful drawings, policy flourished.[5] In 1894, the Lexow Committee, a body empaneled by the New York State Senate, heard testimony that hundreds of policy shops were operating in New York City alone. The committee was surprised to learn that of these shops, the most lucrative were located in poorer districts, where—although individuals wagered minuscule amounts—the overall frequency of betting ensured a healthy take. Committee members were likewise intrigued by the seemingly irrational methods by which players arrived at the numbers they bet on, particularly the widespread use of policy-oriented dream books like Common Sally and The Three Witches, which paired “every word of the dictionary” with a “lucky number opposite.”[6]

In 1851, writing on the pervasiveness of policy in New York City, the anti-gambling advocate J. H. Green had noted that the game found its “victims” among all levels of society, “from the capitalist to the … black washwoman who has left her soap and soiled linen for a speedier path to riches.” Yet, despite observing that policy shops were a “receptacle to all classes and grades of human beings,” Green found that dream books, with their circulations in the “thousands,” were nonetheless “suited to the capacity of the poor and uneducated.” Further, in elaborating on the game’s particular appeal for “the poverty-stricken negro, whose dreams by night and day are of the piles of glittering gold to be won in the next Lottery,” he conjured the specter of a Black player with “dream book in hand … mak[ing] one more sacrifice upon [the] altar of folly and crime.”[7]

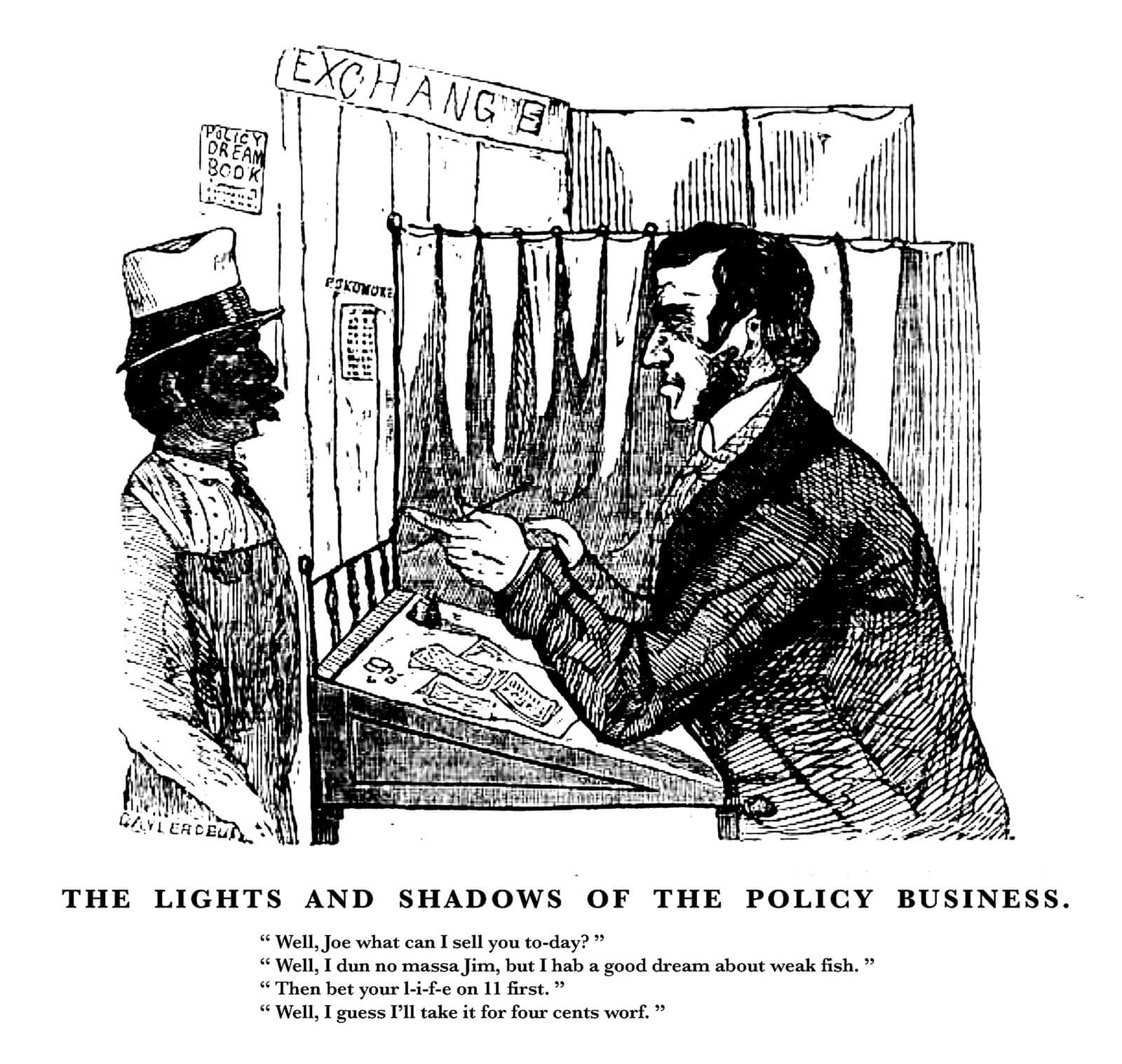

Although policy gambling in New York City was not unique to Black people—and, moreover, it was whites who actually controlled the rackets—moralizing newspapers of the period were likewise quick to identify Black people with the game and its attendant superstitions. An illustration entitled “The Lights and Shadows of the Policy Business,” which ran in a July 1848 edition of The National Police Gazette, is typical. A Black man named Joe seeks advice on betting from a white policy broker he refers to as “massa Jim.” A dream book is affixed to a wall behind him and the word “exchange” is carved into a wooden sign hanging above the door.[8] Consulting the book, Jim tells Joe that, because he had a dream about fish, he should bet on the number eleven for all his life is worth—in this case, four cents.

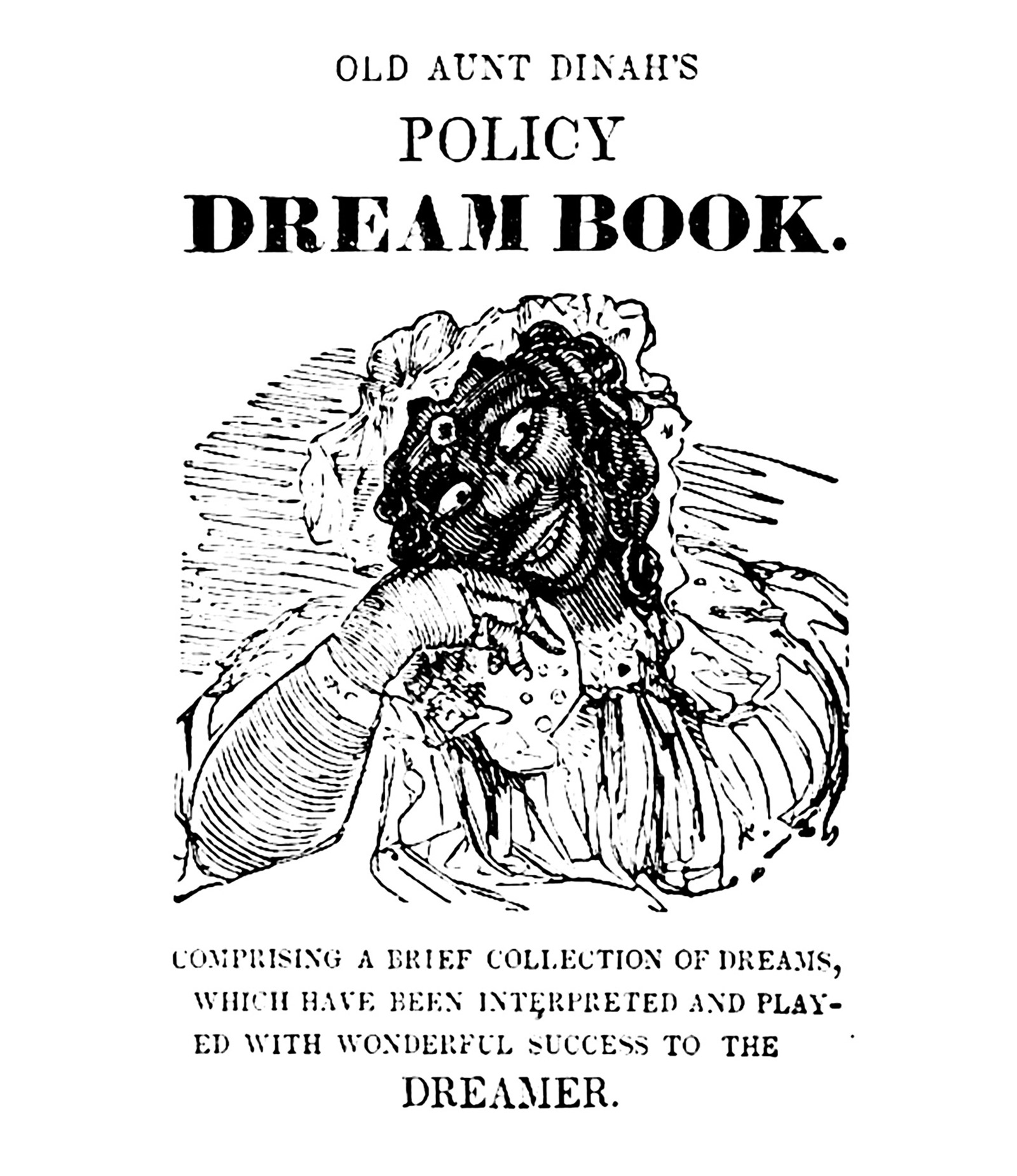

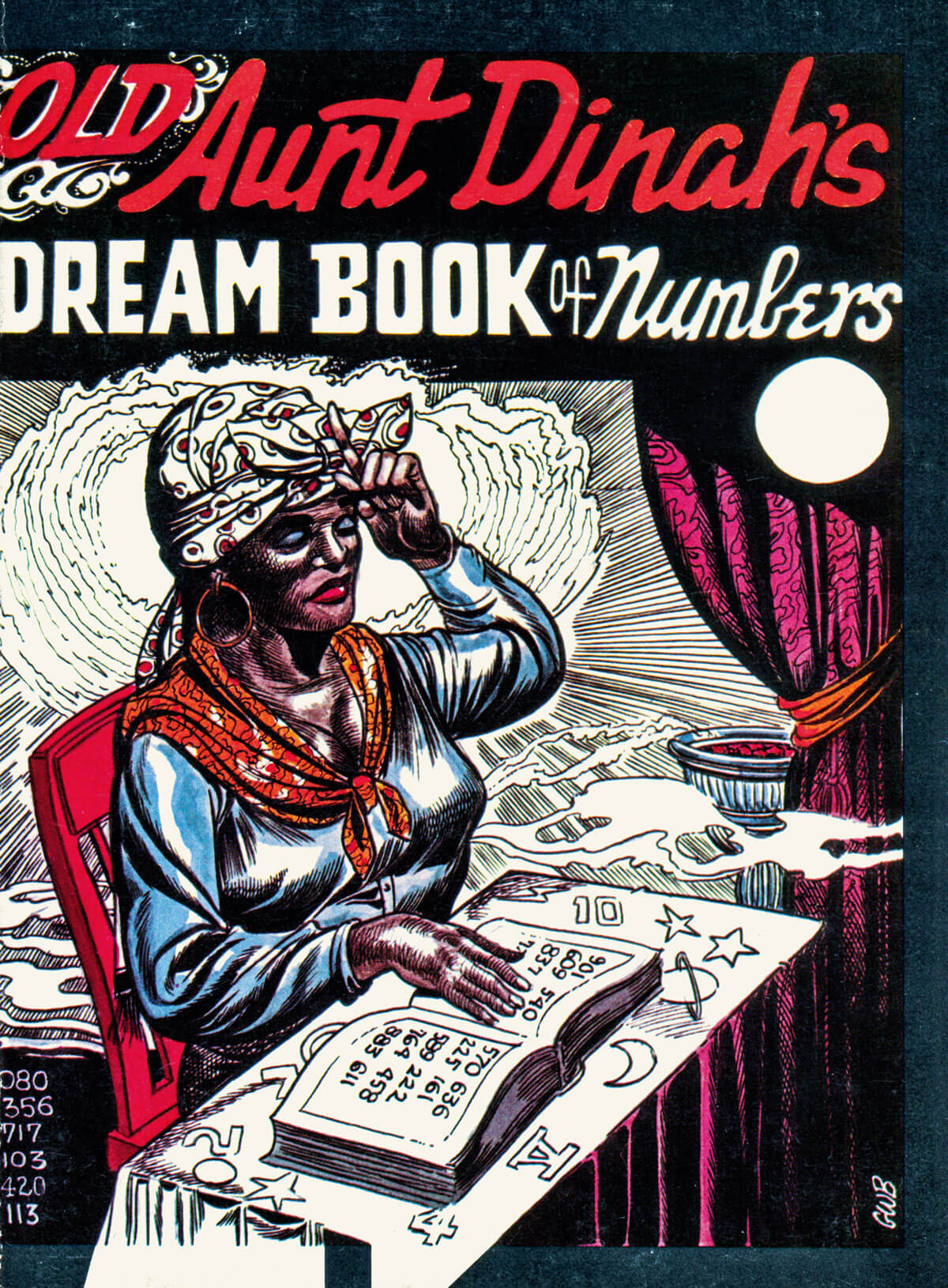

As this racist caricature attests, dream books were central to the day-to-day interactions of typical policy shops. One of the earliest, a pamphlet entitled Old Aunt Dinah’s Policy Dream Book, enjoyed great popularity in the 1830s.[9] Only thirty-two pages in length, Old Aunt Dinah’s contains brief advisories, arranged in no particular order, on the luck of certain dreams relative to policy betting. (“To dream that your sweetheart is very anxious to see you,” one entry explains, “is good for the day of the month, her age and yours in a gig.”) The supposed authoress, Aunt Dinah, is a mammy figure who appears in a crude illustration on the pamphlet’s title page. In a brief preface, she vouches for her interpretations on the basis of their being derived from both “supernatural” revelation and her “successful experience” as a policy gambler. In this, one can see the slightly schizophrenic nature of the Aunt Dinah (and, later, Aunt Sally) character. On the one hand, her authority as a repository of superstitious knowledge and folk wisdom—rooted in nineteenth-century stereotypes about Black Hoodoo and conjure—served as the imprimatur for marketing the dream book. On the other, she was a caricatured reflection of the audience to whom the dream book was marketed, and on whose supposedly outsize superstition the dream book market depended.

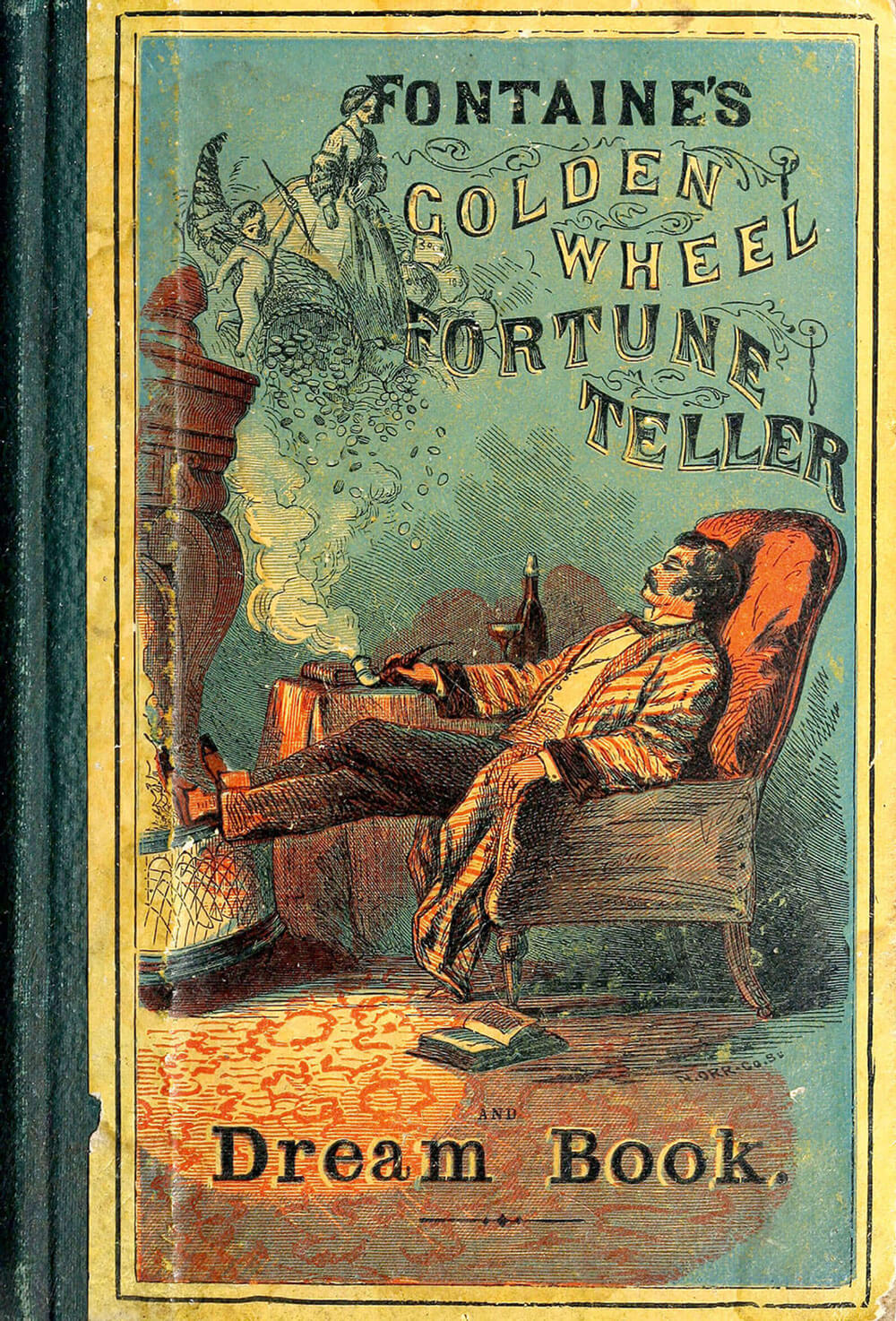

Dream books of the dictionary type, in which specific, non-variable “lucky numbers” were appended to traditional dream interpretations, burgeoned in popularity with the publication in 1862 of The Golden Wheel Fortune Teller and Dream Book by the New York firm Dick & Fitzgerald.[10] According to The Golden Wheel, to dream of snow foretells not only a “pleasant journey” but also the numbers “21, 67, 46.” Dreaming of one’s own execution, meanwhile, indicates good luck and “7, 6, 10.”[11]The Golden Wheel contains hundreds of alphabetized entries like this, as well as supplemental indexes that dispense with interpretations altogether, listing only the lucky numbers associated with each dreamt-of object. These supplemental indexes cover, among other things, names, months, days of the week, and playing cards. A potpourri of short essays on topics including phrenology, divining rods, and “nutshell witchery” rounds out the two-hundred-page collection, abutting awkwardly with numerous pages of mail-order advertisements for Dick & Fitzgerald titles, books which—The Golden Wheel included—are presented as wholesome and affordable parlor entertainments. This format seems to have been quite a success, paving the way for subsequent Dick & Fitzgerald dream books in the same mold. Other publishers followed suit, establishing it as the de facto template for the genre.

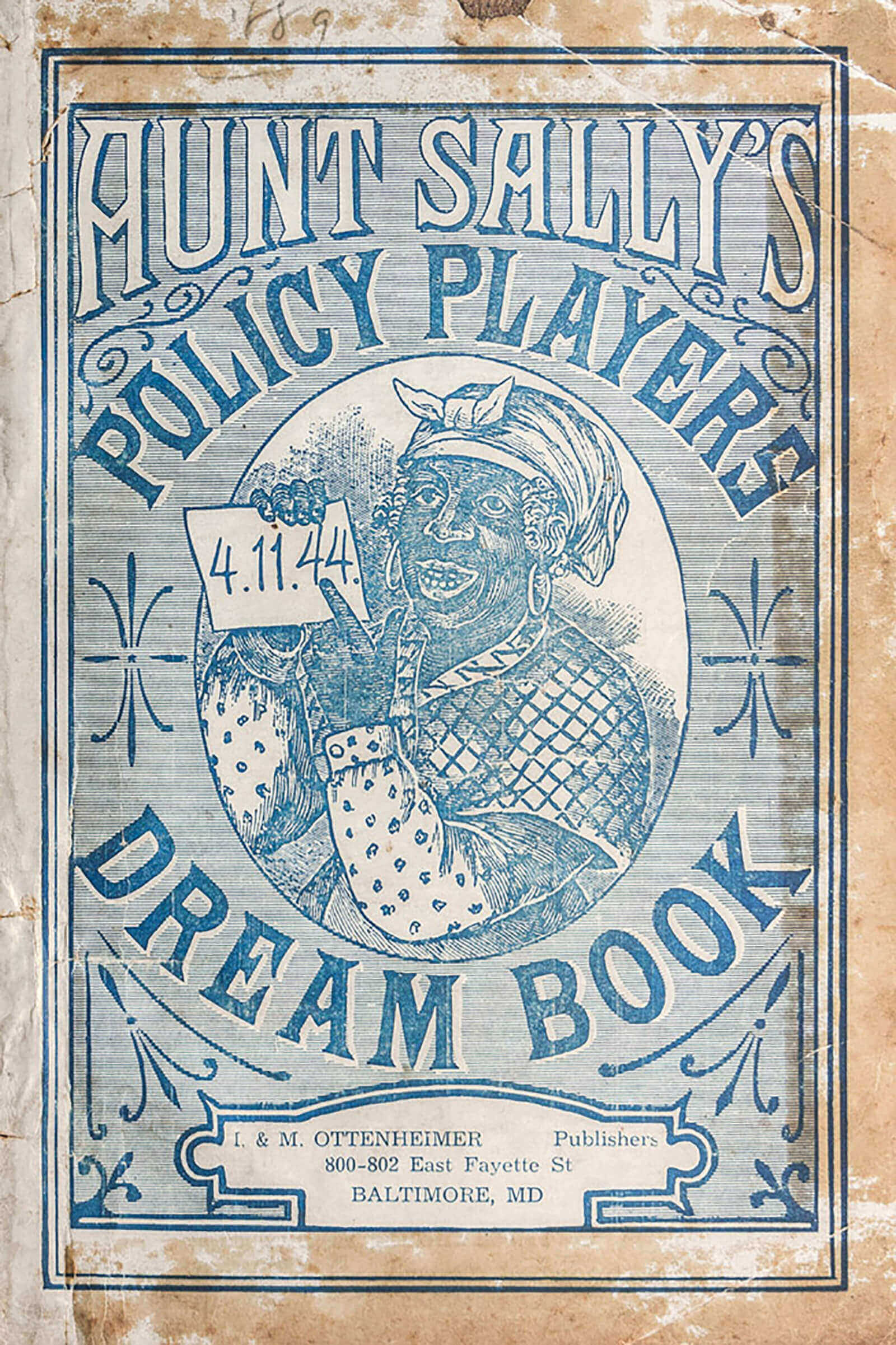

The New York firm Wehman Bros., arguably the most significant dream book publisher to follow the Dick & Fitzgerald model, published Aunt Sally’s Policy Players Dream Book in 1889. Like The Golden Wheel, it consists of dream interpretations paired with lucky numbers, and supplemental lists in which dreams are paired with lucky numbers alone. But Aunt Sally’s contains far less esoteric padding; an abridged version of “Napoleon’s Oraculum,” a do-it-yourself system of divination, is the only section of the book not directly related to policy betting. The parlor-room pretense has disappeared: where The Golden Wheel presents itself as polite entertainment, Aunt Sally’s very title announces the book as an aid for illicit gambling. The cover artwork is equally straightforward. It depicts a Black washerwoman, the eponymous Aunt Sally, holding up a sign with the sequence “4.11.44,” a gig commonly used as a metonym for policy gambling and known to be popular with African American gamblers.[12] Half a page is even given over to a “combination table” illustrating the different ways in which a policy player could apportion groups of lucky numbers into gigs and other plays.[13]

As purveyors of mass entertainment, the leading dream book publishers of the nineteenth century—Dick & Fitzgerald, Wehman Bros., and the Baltimore-based I. & M. Ottenheimer—all sold minstrel song and joke books that traded heavily on racial stereotypes. The figure of Aunt Sally is certainly in keeping with the imagery of such offerings, with the difference that ridicule does not seem to be the primary selling point. Rather, Aunt Sally is used as a byword for supernatural folk wisdom. In this, she is not unique. Dream books almost uniformly present themselves as originating from the writings of purportedly “mystical” personages, often based on ethnic stereotypes. Characters like Mehemet Ali, Madame Juno, and the Gypsy Witch, among others, all lend their names and supposed authority to dream books of the late nineteenth century. The prima facie plausibility of these credentials seems to have been less important than the air of exoticism they exuded. Consider the title Mother Shipton’s Oriental Dream Book, published by Dick & Fitzgerald in 1863, which couples an English witch of dubious historicity with the adjective “oriental.” The crass and often incoherent exoticism of dream-book branding mirrored the arbitrariness of the numerology within: What absurd logic of quantification could have led Aunt Sally’s to assign the sequence “2, 11, 22” for “drinking out of pump” and the slightly different “2, 12, 22” for “drinking out of hydrant”? Or to the altogether more unnerving ascription of numerical values to different ethnicities, such as “6, 14, 66” for “colored man” and “10, 18, 44” for “white person”?[14]

• • •

In the 1920s, a new form of numbers gambling was invented in which bets were taken on three-digit figures. Winning numbers were derived from a pair of financial figures released daily by the New York Clearing House Association, an institution that administered bank-to-bank monetary transactions. These figures—the daily bank clearings total and the credit balance of the New York Federal Reserve Bank—were printed together in most major newspapers. The second and third digits of the clearings total would be combined with the third digit of the Federal Reserve credit balance to arrive at a random—and thus unfixable—three-digit result. For example, if on a given day the clearings total was $589,000,000 and the credit balance was $116,000,000, then the winning number would be 896. Although policy gambling remained popular in Chicago, this new game of “numbers” quickly became preeminent in cities along the East Coast. In Harlem, where it originated, playing the numbers became a cornerstone of daily life. The streets would hum with final wagers in the run-up to 10:00 am, when—on the steps of the ornate Clearing House building on Cedar Street in Lower Manhattan—the Clearing House figures were released to the press and general public.[15]

Although numbers typically had payoff odds of 600:1—allowing for the possibility of massive windfalls on large, one-off wagers—the insinuation of the game into daily life occurred as a result of widespread daily betting in small, nickel-and-dime amounts. This regular rhythm of play ensured a steady income for the legions of “runners” (replacing the brokers of the policy system) necessary to collect bets and distribute payouts. The Black “kings” and “queens” to whom these runners reported amassed enormous wealth as the heads of this underground economy, which—owing to the dearth of Black-owned businesses in Harlem—represented the majority of Black capital in the city. With white-owned banks unwilling to lend to Black people, the kings often acted as sources of credit, assuming positions of prominence in the community as bankers and patrons. Money from numbers gambling helped to finance small businesses, churches, fraternal organizations, and Negro league baseball clubs like the New York Cubans, among other ventures.[16]

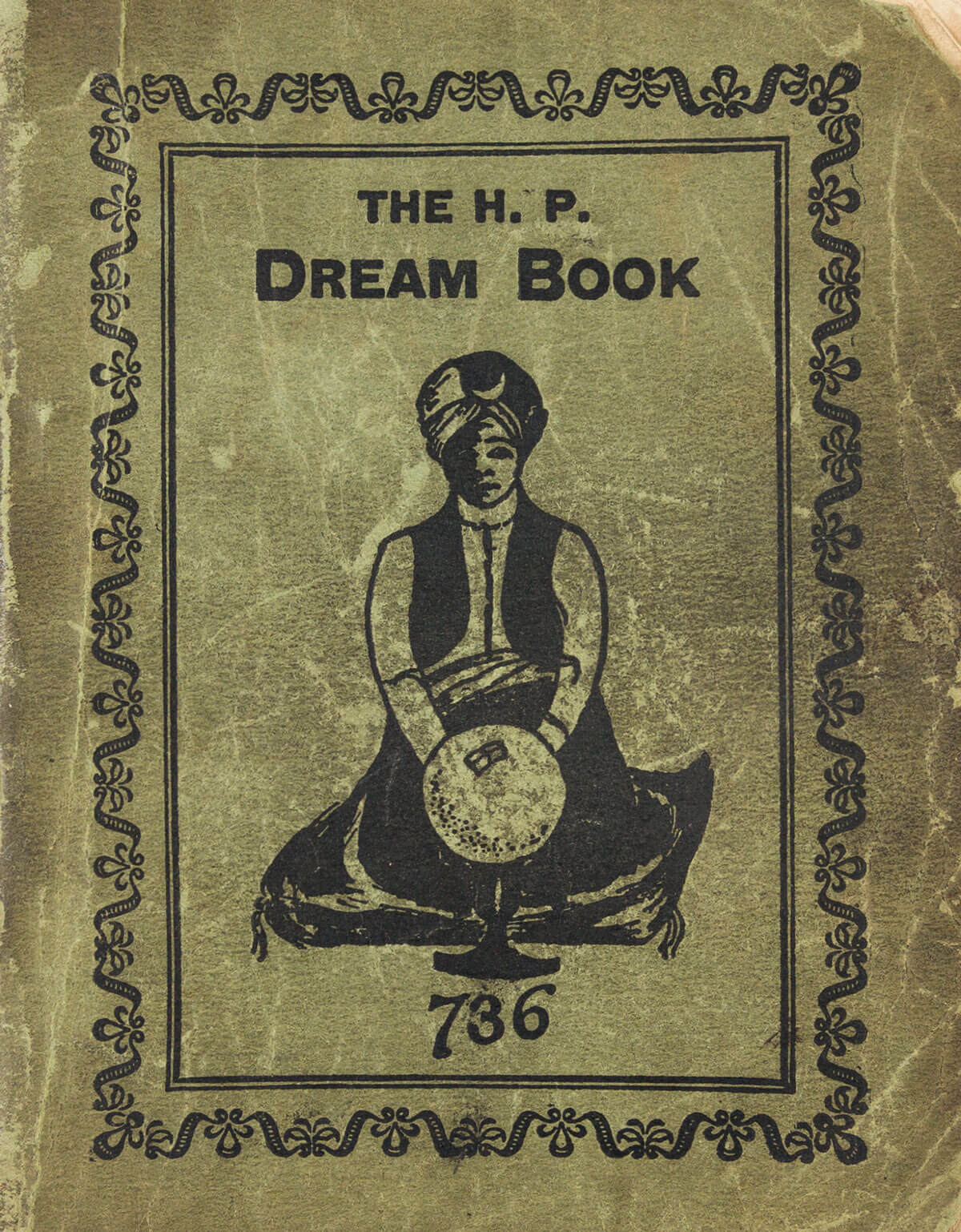

Because pre-1920s dream books had been written in keeping with the rules of policy, which only allowed for numbers with a maximum of two digits, the rise of three-digit numbers gambling created a gap in the market. Herbert Gladstone Parris, a Barbadian resident of Harlem, was among the earliest and most successful to fill the void. Born in 1893, Parris immigrated to the United States in 1917 and settled in Harlem, initially finding employment as a shipyard carpenter in Newark, New Jersey. In December 1926, Parris authored and independently published The H. P. Dream Book under the pseudonym “Prof. Uriah Konje.” In place of two-digit combinations, a single three-digit number in bold accompanies each of the book’s entries. The H. P. Dream Book’s enduring popularity served Parris as the foundation for a lucrative publishing business, which included titles such as The Combination Dream Book in 1927, The Lucky Star Dream Book in 1928, and The Success Dream Book (authored under another nom de plume, “Professor de Herbert”) in 1931. By 1938, his publishing income was sufficient to purchase the Westchester estate of the late Charles Stoneham, former owner of the New York Giants baseball franchise, for a sum in excess of $40,000.[17]

Although Parris’s titles have much in common with earlier policy-oriented dream books, they imbue the genre with a distinctive, personal voice. At times, the inflection is humorous, as in The Lucky Star Dream Book’s wry interpretation of “insane”:

INSANE—To dream of being insane denotes long life and happiness. 381[18]

Other entries are bawdy:

HAIRY MONSTER—To dream that you see a hairy monster denotes excessive pleasure. 368[19]

Still others seem earnestly informed by Parris’s own occupational experiences:

DOCK—To dream that you are at the dock denotes that you are being robbed out of your labor. To work on the dock denotes a dreary life. 347

• • •

PUBLISH—To dream that you publish something, foretells that you will change your present position for one that will bring you a much greater income. 919[20]

Parris is similarly sincere when espousing political convictions, such as in this entry for “Garveyism”: “To dream of this doctrine denotes power and dignity. This is a very good dream to all; it promises wealth and much happiness. 591” or the message of striving and racial uplift he addresses “TO THE COLORED PEOPLE OF THE WORLD” in The H. P. Dream Book.[21] Subtler, but no less revealing, is Parris’s use of lucky numbers to cross-index certain entries. In The H. P. Dream Book, “Castles in the Air” and “Coffin” both equate to 999. Likewise, “Hood,” “Ghostly,” and “Ku Klux Klan” share the number 000, as does the entry for “Professor of Nothing.”[22]

Assuming that “Professor of Nothing” refers to Parris’s pseudonymous title—a play on the nothingness of dreams and the fraudulence of Professor Uriah Konje’s credentials—its numerical equivalence with the entry for “Ku Klux Klan” suggests a degree of moral ambivalence about his publishing endeavors. Did Parris on some level perceive the vice of gambling as inimical to the cause of racial empowerment he advocated? The admonishing epigraph that prefaces The Lucky Star Dream Book provides further evidence for such a reading: “The heights by great men, reached and kept, were not attained by sudden flight; but they, while their companions slept, were toiling upwards through the night.”[23]

One indicator of Parris’s success is the tenacity with which he fought attempts to bootleg his work. In 1929, noticing a drop in newsstand orders, he hired the detective agency of Herbert S. Boulin to investigate. When the agency uncovered evidence that competitors were selling facsimiles of his work, Parris sought copyright injunctions against several New York publishers, among them Wehman Bros.[24] However, Parris claimed that the culprit responsible for the majority of the bootlegging was Harry Seligman, the white proprietor of Harry Treat’s Company, a book and patent medicine establishment catering to South Philadelphia’s African American community. Parris alleged that Seligman, formerly the Philadelphia distributor for his books, was undercutting his newsstand sales with bootleg editions, not only in Philadelphia but also in New York and Atlantic City.

For his part, Seligman claimed he was only reselling books legally obtained from Parris. Yet in spite of this defense, he also filed a motion asking that Parris’s civil suit be dismissed on the grounds that The H. P. Dream Book was “a fraud upon the public ... calculated to deceive and constitut[ing] an accessory to gambling and other practices harmful to the public morals.” The speciousness and hypocrisy of his argument notwithstanding, Seligman prevailed in both the civil case and a related criminal indictment for copyright infringement.[25] Seligman’s South Philadelphia storefront—rebranded as Harry’s Occult Shop—remained a fixture in the community until its closure in 2014.[26]

On later printings of The H. P. Dream Book, the cover art awkwardly accommodates an added warning on piracy: “Beware of Imitations: Only the original H. P. Dream Book bears this signature: Prof. Uriah Konje.” On the one hand, this disclaimer is evidence of the degree to which, following his defeats in court, bootlegging remained a problem for Parris. Beyond that, however, it also speaks to the centrality of the Konje persona as a selling point, a presentational element very much in line with the caricatured author figures of earlier dream books. Yet, for all that the pseudonyms used by Parris are of a piece with such caricatures, they are just as much products of the Orientalism that was prevalent among the ubiquitous street performers and spiritualists of Harlem during the 1920s and 1930s. In an America largely unacquainted with actual Asian culture, the East possessed an air of exoticism ripe for exploitation by stage magicians, fortune-tellers, and confidence men, many of whom adopted “Eastern” trappings like turbans, tunics, and crystal balls. Some went so far as to pretend to have Hindu or East Asian heritage. Dream books were a natural vehicle for this Orientalist tendency, and its stage affectations became nearly de rigueur in the genre’s packaging, even for authors, like Herbert Parris, with no connection to fortune-telling or the stage.[27]

One notable Harlem spiritualist who diversified into dream books was Madame Fu Futtam, born Dorothy Matthews, a Jamaican immigrant who described herself as a “mysterious scientific East Indian Yogi.” Futtam’s Magical-Spiritual Dream Book, first published in 1935, supplements lucky number dream interpretations with sections on fortune-telling and the use of magic to win and influence lovers—a window into the type of services she offered in person. The book’s introduction helpfully instructs readers to “go and see her at her office, 20 West 129th Street, New York City.”[28] The cover features a prayer:

Now I lay me down in Slumber.

When I sleep and When I Wake,

Pray God I Hit the Number.

Madame Fu Futtam gained notoriety as the mistress and, later, second wife of labor organizer Sufi Abdul Hamid, born Eugene Brown, whose anti-Semitism earned him the moniker “The Black Hitler of Harlem.” Hamid’s first wife was the numbers queen Stephanie St. Clair, infamous among other things for her hard-fought, though ultimately unsuccessful, efforts to resist the takeover of the Harlem numbers racket by white gangsters in the early 1930s. Her marriage to Hamid deteriorated in the final months of 1937 as a result of his affair with Fu Futtam.[29] Jilted, St. Clair denounced Fu Futtam in the press as a “racketeer” who took advantage of “poor colored men and women.” She gave this description of Fu Futtam’s modus operandi:

The spiritualists will ask ten dollars for a number. The price often comes down to fifty cents and the number is given. When the number does not play, the customer is told that an evil spirit prevents the number from playing, and for anywhere from one to two hundred and fifty dollars, the spirit can be removed.[30]

In January 1938, St. Clair ambushed her estranged husband with a .38 caliber revolver, firing three shots. The bullets narrowly missed their mark—Hamid was grazed on the arm and chest—and St. Clair was arrested when police arrived at the scene.[31] Following the ordeal, Hamid attempted to reinvent himself as a populist religious figure in the mold of Father Divine, an African American minister-cum-cult leader then at the height of his national influence. With rumored funding from Fu Futtam, he opened the Universal Holy Temple of Tranquility, Inc. in Harlem (an attempt to emulate the communal “heavens” of Divine’s International Peace Missions movement, which provided lodging and social services to the needy) and bestowed upon himself the title His Holiness Bishop Amiru Al-Mu-Minin Sufi Abdul Hamid.[32] Hamid also made plans to emulate Father Divine’s aerial publicity tours, buying a secondhand Cessna airplane and hiring a pilot for flying lessons.[33] However, these plans never reached fruition. On 31 July 1938, the Cessna unexpectedly ran out of fuel shortly after taking off from Roosevelt Field in Long Island. Hamid and his flight instructor were killed in the resulting crash, while Madame Fu Futtam watched helplessly from the hangar. The New York Amsterdam News, a leading Black paper that covered Hamid’s funeral with the headline “Mme. Fu Futtam Slipped Up on Forecasting Doom of Sufi,” examined the incident’s impact on Fu Futtam’s reputation, reporting that “doubting Harlemites” now wondered how the supposed clairvoyant could have failed to foresee the crash. The situation had placed Fu Futtam in quite the logical bind: either she was a charlatan, or else her inaction in stopping the flight meant she was complicit in her husband’s death.[34]

• • •

On 1 January 1931, the New York Clearing House halted the publication of its daily totals in an attempt to eliminate what had by then become known, to their consternation, as the “Clearing House numbers game.” Faced with the absence of these figures, racketeers simply adopted others, deriving winning digits from, for instance, New York Stock Exchange stock and bond listings or the results of pari-mutuel racetrack betting. Sometimes the figures were of particular relevance to the localities where they were used: on the Pacific Coast, the total poundage of the daily salmon catch; in mining regions, the daily tonnage of shipped ore. Although the numbers game continued to thrive, the Clearing House no longer served as the locus for the shadow economy associated with it.[35]

Following the switch, numbers gamblers began inundating the New York Stock Exchange with letter and telegram requests for tips, not realizing that the institution itself was distinct from the rackets that used its trading index. The exchange answered these requests with a customary “do not inquire,” but kept the messages on file. They speak to the confused desperation of gamblers in need of a payout, as well as their eagerness to believe in a “direct line” to winning plays.[36] Dream books, which catered to this same desperation, were quick to address the upheaval: new titles now advertised the applicability of their lucky numbers to specific types of racket, such as those based on the stock exchange and pari-mutuels.

The oncoming repeal of Prohibition brought additional changes. Seeking new sources of revenue, white mobsters seized control of numbers betting in Black urban areas. Although superficially little changed—the rackets remained largely in the hands of Black operators—most of the profit was now given over to the mob rather than redistributed within the Black community. Concurrently, the mob also introduced the numbers game to nonblack gamblers, significantly expanding the game’s demographic and geographic reach.[37] Dream books, in turn, reflected this expansion. For instance, The Italian Dream Book, published in 1932, targets a specifically Roman Catholic audience. In addition to a bilingual dictionary, it includes a quasi-liturgical calendar in which—for each day of the year—a quote from scripture is coupled with a three-digit lucky number. “If you wish to have dreams of value,” it advises readers, “you must keep religion in your heart every day in the year.”[38]

Yet, while the developments of the 1930s were initially a spur to dream book publishing, the stimulus was short-lived: the following decades saw the genre enter into a sustained period of decline. Demand still existed, but genuinely new offerings grew fewer and farther between; cheap reprints and clumsily emended re-editions apparently satisfied the market. Meanwhile, the establishment of modern state lotteries in the 1960s and 1970s—including the rollout of legal three-digit number games—siphoned money that may have otherwise been channeled into illicit games.[39] Dream books were just as useful for legal gambling, but given the genre’s longstanding association with criminal rackets, it seems likely that their contemporaneous downturns were related.

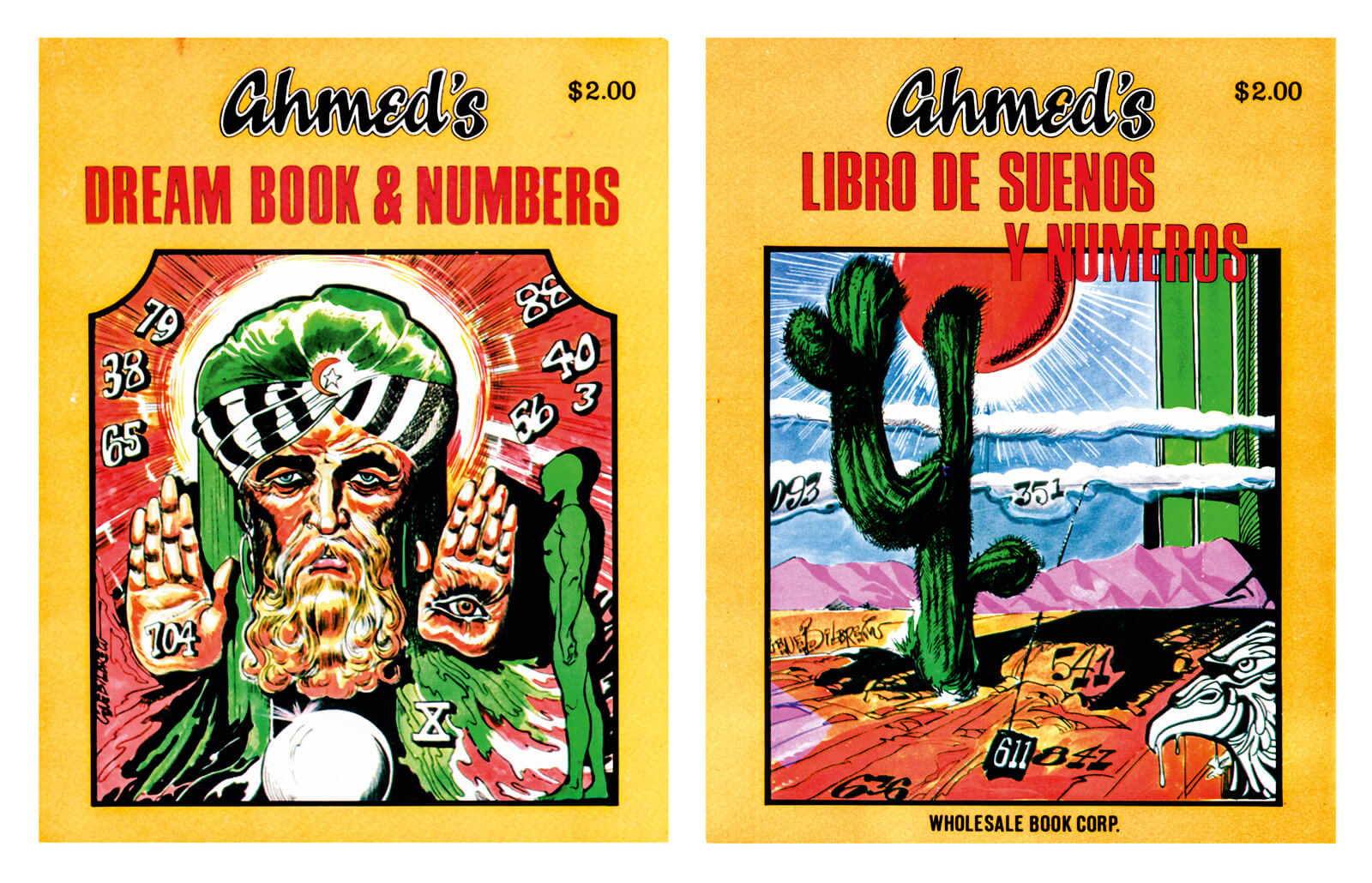

Arguably, the last dream books of any note were published in 1972 by Wholesale Book Corp., a Times Square–based producer and distributor of pornographic books and movies. Contrary to the miserly trends then marking the genre’s collapse, Wholesale released a slate of titles distinguished by their impressive cover art, designed by African American illustrator and fetish cartoonist Eugene Bilbrew. Bilbrew began his career as a porn artist in the 1950s, producing bondage-themed comic strips and paperback covers for a variety of publishers, including Wholesale Book. Edward Mishkin, the mob-connected owner and overseer of Wholesale Book, was also the proprietor of several adult bookstores in Manhattan. In 1974, Bilbrew suffered a fatal drug overdose in the back room of a bookstore Mishkin operated on 42nd street.[40]

At present, a handful of dream book publishers remain in business. However, the original titles they sell are shoddy and homogenous affairs, wholly lacking in personality—pale imitations of the genre in its heyday.

- Harry B. Weiss, Oneirocritica Americana: The Story of American Dream Books (New York: The New York Public Library, 1944), pp. 9–10, 14–16.

- Gustav G. Carlson, “Number Gambling: A Study of a Culture Complex” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1940), pp. 16–23; Anthony Shafton, Dream-Singers: The African American Way with Dreams (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2002), pp. 230–231. Other plays include “saddles” (bets on two-number combinations), “horses” (four-number combinations), “jacks” (five-number combinations), and bets on individual numbers.

- Shane White, Stephen Garton, Stephen Robertson, and Graham White, Playing the Numbers: Gambling in Harlem between the Wars (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), pp. 32–57. The almost parodic mirroring of legitimate financial transactions is a recurring motif in the history and slang of illegal lottery gambling.

- Gustav G. Carlson, “Number Gambling,” p. 21.

- Shane White, Stephen Garton, Stephen Robertson, and Graham White, Playing the Numbers, p. 37.

- Ibid., pp. 53–55; Report and Proceedings of the Senate Committee Appointed to Investigate the Police Department of the City of New York (Albany: James B. Lyon, State Printer, 1895), vol. 3, pp. 3243–3246, 3253.

- J. H. Green, A Report on Gambling in New York (New York: J. H. Green, 1851), pp. 44–45, 91–92.

- Shane White, Stephen Garton, Stephen Robertson, and Graham White, Playing the Numbers, pp. 38–40. Policy shops often advertised themselves as “exchange offices,” an innocuous billing that served as a code word to gamblers.

- Herbert Asbury, Sucker’s Progress: An Informal History of Gambling in America from the Colonies to Canfield (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1938), pp. 94–95.

- Harry B. Weiss, Oneirocritica Americana, pp. 14–15.

- Many dream book interpretations adhere to the principle that, in dreams, meaning exists in reverse of real-world expectations. For example, in The Golden Wheel, dreams involving difficulty are interpreted as follows: “If you imagine in your dream that you are in great difficulty, or in personal danger of any kind, it is a favorable sign, as such dreams always go by contrary. 17, 27.” See Felix Fontaine, The Golden Wheel Fortune Teller and Dream Book (New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1862), p. 22.

- Shane White, Stephen Garton, Stephen Robertson, and Graham White, Playing the Numbers, pp. 43–44, 52. The combination “4–11–44” was known variously as the “washerwoman’s gig” and “the negro’s lucky numbers.”

- Aunt Sally’s Policy Players Dream Book (New York: Henry J. Wehman, 1889), p. 49. Dream books allow for far more interpretative agency than one might initially suppose. For instance, because a dream might contain multiple objects, each with its own entry and corresponding lucky numbers, a gambler is free to choose combinations from among all of those numbers, mixing and matching according to their own preferences and personal superstitions.

- Ibid., pp. 71, 115, 117. Other racially charged entries include: “a colored genteel n-----,” “dead colored man,” “dead colored woman,” “Dutchman,” “Irishman,” “Jew,” “Jewess,” “Negro,” and “white man and colored woman.”

- Shane White, Stephen Garton, Stephen Robertson, and Graham White, Playing the Numbers, pp. 5, 12–14.

- Ibid., pp. 14, 18, 66, 154–159, 212–220, 224–225. The philanthropy of numbers banker Casper Holstein is particularly notable. He contributed to hospitals, scholarships, Fisk and Howard universities, disaster relief in the Virgin Islands, a dormitory for girls in Liberia, Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, and Opportunity magazine’s annual literary prize of $1,000, which counted Langston Hughes among its recipients. According to a possibly apocryphal account, it was Holstein himself who—while working as a porter in a downtown Manhattan department store—first hit on the idea of using Clearing House totals as a lottery system. With savings from his job, he set himself up as a banker and originated the game in Harlem.

- “$40,000 Reputedly Paid by Harlemite for Ritzy Home of Baseball Magnate,” The Pittsburgh Courier, 7 May 1938.

- Uriah Konje [Herbert Gladstone Parris], The Lucky Star Dream Book (New York: G. Parris, 1928), p. 94.

- Ibid., p. 86.

- Ibid., pp. 52, 142.

- Ibid., p. 79; Prof. Uriah Konje [Herbert Gladstone Parris], The H. P. Dream Book (New York: G. Parris, 1926), p. 88.

- Uriah Konje [Herbert Gladstone Parris], The H. P. Dream Book, pp. 14, 16, 29, 34, 37, 51.

- Uriah Konje [Herbert Gladstone Parris], The Lucky Star Dream Book, p. 3.

- “Three Here Are Charged with ‘Number-Dream Books’ Copyright Thefts,” The Philadelphia Tribune, 6 November 1930; Shane White, Stephen Garton, Stephen Robertson, and Graham White, Playing the Numbers, pp. 94–95. Given his praise for Garveyism, there is an irony to Parris’s hiring of Herbert S. Boulin. Boulin, a Jamaican immigrant to Harlem, launched his sleuthing career by outing himself as a former informant for the FBI, having spied against Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association.

- Bill of Complaint pp. 1–8, and Answer to Bill of Complaint and Motion to Dismiss pp. 3–5, Parris v. Seligman, Equity No. 5531 (E.D. Pa, 1929); Verdict, United States v. Seligman, Criminal No. 4644 (E.D. Pa, 1931).

- Carolyn Morrow Long, Spiritual Merchants: Religion, Magic, Commerce (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2001), pp. 156–157. In 1945, Seligman sold Harry’s Occult Shop to his brother and moved to Los Angeles, where he and his wife began a small candle-manufacturing business, the Cross Candle Company. Harry passed away in 1962 and Cross Candle folded in 1965, when protesters burnt down the factory during the Watts riots. As a result of the blaze, the scent of “magic” candle and “lucky” incense products blanketed the area. Interviewed by Long, Nettie Seligman, Harry’s widow, recalled that “the firemen told me it was the nicest fire they ever smelled.” Somewhat defensively, she goes out of her way to insist: “They didn’t burn my store deliberately; they loved my store.”

- Philip Deslippe, “The Hindu in Hoodoo: Fake Yogis, Pseudo-Swamis, and the Manufacture of African American Folk Magic,” Amerasia Journal, vol. 40, no. 1 (2014).

- Lashawn Harris, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2016), p. 98; Madame Fu Futtam, Fu Futtam’s Magical-Spiritual Dream Book, rev. ed. (New York: Empire Publishing, 1939), p. 3.

- Shane White, Stephen Garton, Stephen Robertson, and Graham White, Playing the Numbers, pp. 159–163; “Sufi Wooed St. Clair in ‘Darkened Room,’” The New York Amsterdam News, 29 January 1938.

- Lou Layne, “Madame Raps ‘Black Hitler,’” The New York Amsterdam News, 20 November 1937.

- “$6,000 Bail for Mme. St. Clair,” The New York Amsterdam News, 22 January 1938.

- Marvel Cooke, “Sufi Opens Rival ‘Heaven,’” The New York Amsterdam News, 16 April 1938.

- Judith Weisenfeld, New World A-Coming: Black Religion and Racial Identity during the Great Migration (New York: New York University Press, 2016), pp. 252–253. See also “Harlem ‘Hitler’ Killed,” The Pittsburgh Courier, 6 August 1938.

- “Mme. Fu Futtam Slipped Up on Forecasting Doom of Sufi,” The New York Amsterdam News, 6 August 1938. The Black press also mooted the possibility that Father Divine or Stephanie St. Clair may have had a hand in orchestrating the crash. See Ralph Matthews, “Was It Curse of Father Divine or Did Madam St. Clair Kill Sufi?,” The Afro-American, 6 August 1938.

- Shane White, Stephen Garton, Stephen Robertson, and Graham White, Playing the Numbers, pp. 18–19, 27; Gustav G. Carlson, “Number Gambling,” p. 12. In 1964, the Clearing House moved to new headquarters and its Cedar Street building was demolished. Zuccotti Park, the focal point for the Occupy Wall Street movement, is located where it once stood.

- Gustav G. Carlson, “Number Gambling,” pp. 163–206.

- Shane White, Stephen Garton, Stephen Robertson, and Graham White, Playing the Numbers, pp. 25–29.

- Prof. Frazzetti, The Italian Dream Book (Baltimore, MD: Daily Press Publishing, 1932), p. 3.

- Charles T. Clotfelter and Philip J. Cook, Selling Hope: State Lotteries in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989), pp. 55–59, 130–33. The degree to which lottery sales impinged upon illegal betting is debatable.

- Brittany A. Daley et al., eds., Sin-A-Rama: Sleaze Sex Paperbacks of the Sixties (Los Angeles: Feral House, 2005), pp. 63–64.

Christopher W. Vandegrift is a Philadelphia-based writer and artist. For more information, see www.christophervandegrift.com.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.