The Softest of Powers

A short history of panda diplomacy

Chia-Wei Hsu

Giant pandas are found in the wild only in a few mountain ranges in China, primarily in Sichuan province, which means that China controls the supply of one of the world’s most beloved animals. Pandas became a key component of China’s diplomatic relations beginning in the mid-twentieth century, with the first instance of such “panda diplomacy”—as the practice of offering the bears as the highest official gift came to be called—occurring in 1941 when Madame Chiang Kai-shek and her sister gave a pair of pandas to the United States in gratitude for assisting the country in its war with Japan. This began a tradition that continued through the Cold War to the present day, with the animal playing a vital role in China’s relationship with countries including Taiwan, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

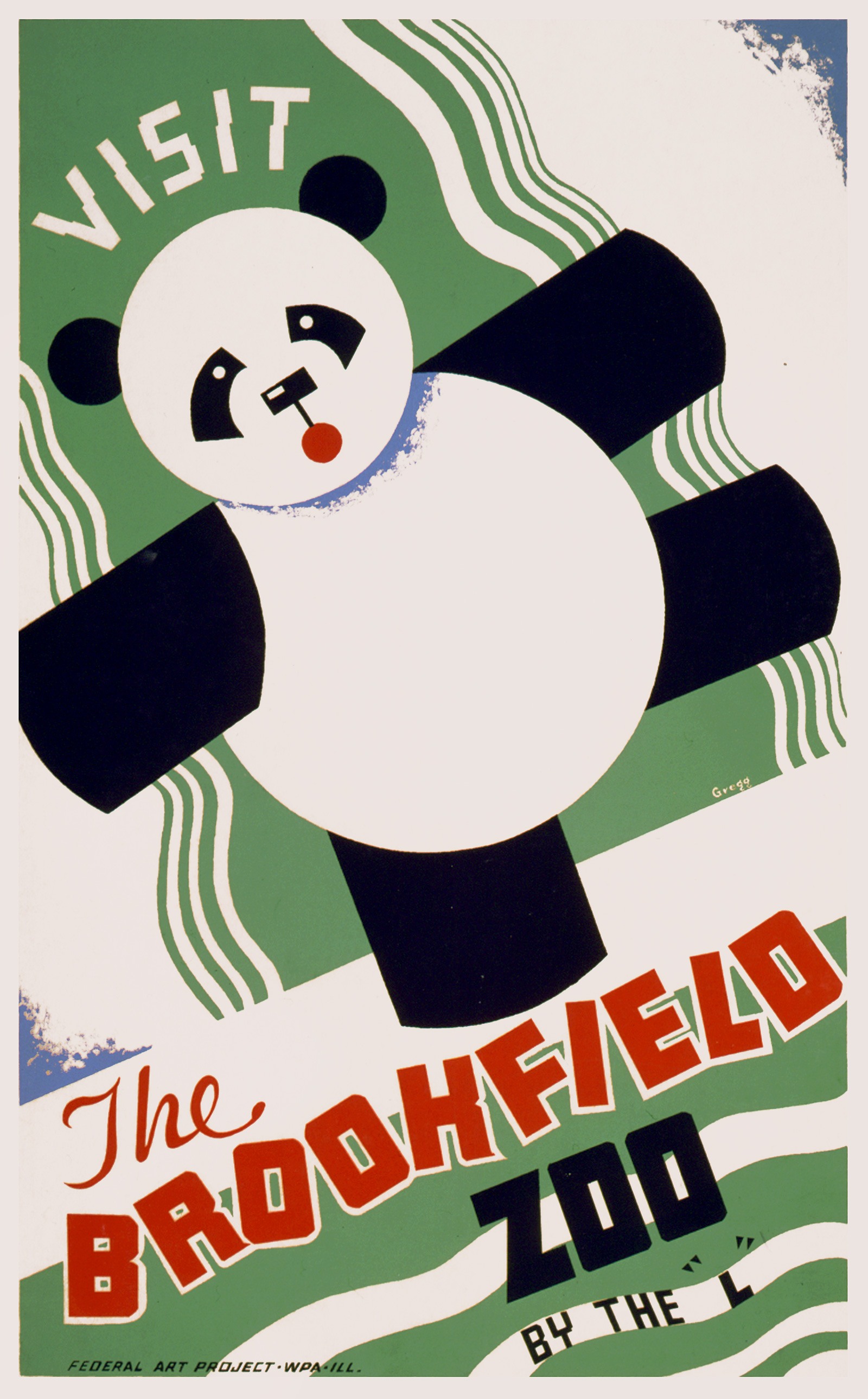

In 1936, the first living panda arrived in the West. It was brought to the United States illegally by Ruth Elizabeth Harkness, a fashion designer from New York whose husband, William, had died that February in Shanghai while preparing an expedition to capture pandas in Sichuan. Harkness traveled to China and took over the expedition, hiring a hunter who eventually caught a panda, to which she gave a female name—Su-Lin. On the forms required to clear Chinese customs, she described the animal as “One dog—$20.00.” Harkness disembarked with Su-Lin in San Francisco and was soon back in New York, where she kept the panda in her apartment while she waited for an offer of a permanent home for her. Su-Lin was eventually bought by Brookfield Zoo in Chicago, where in the first three months after her debut in August 1937, she was seen by more than 325,000 visitors. Within two years of arriving in the United States, Su-Lin was dead; the ensuing dissection revealed that the animal had, in fact, been male.

The next episode in the modern-day craze for the bear featured Ming, one of a group of six pandas bought in 1937 by the American banker-turned-adventurer Floyd Tangier Smith, who had partnered with Harkness’s husband on his aborted expedition. Yangtze River traffic to Shanghai having been blocked by the Japanese in their invasion of China, Smith had to arrange for the pandas to be transported instead to Hong Kong by truck. Only five ultimately made it alive onto the ship, and two weeks after arriving in London, another died from a lung infection. Smith sold one of the pandas to a German businessman, who took it on a tour of zoos in Germany. The remaining three pandas were placed at London Zoo, and were named by the zookeeper after Chinese dynasties—Tang, Sung, and Ming. This last name was given to the youngest panda, a cub, as that dynasty was the most recent of the three. Ming soon became a superstar in London; her image frequently appeared in cartoons, newspapers, and magazines, and on toys and postcards. Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret were among the smitten. When the girls visited the zoo, Ming stole a flowery umbrella from Margaret and then, making noises and covering her eyes, lay on her back for the princesses to tickle her belly.