Cabinet Is Safe

The emblems of German fire insurance

Sonja Lau

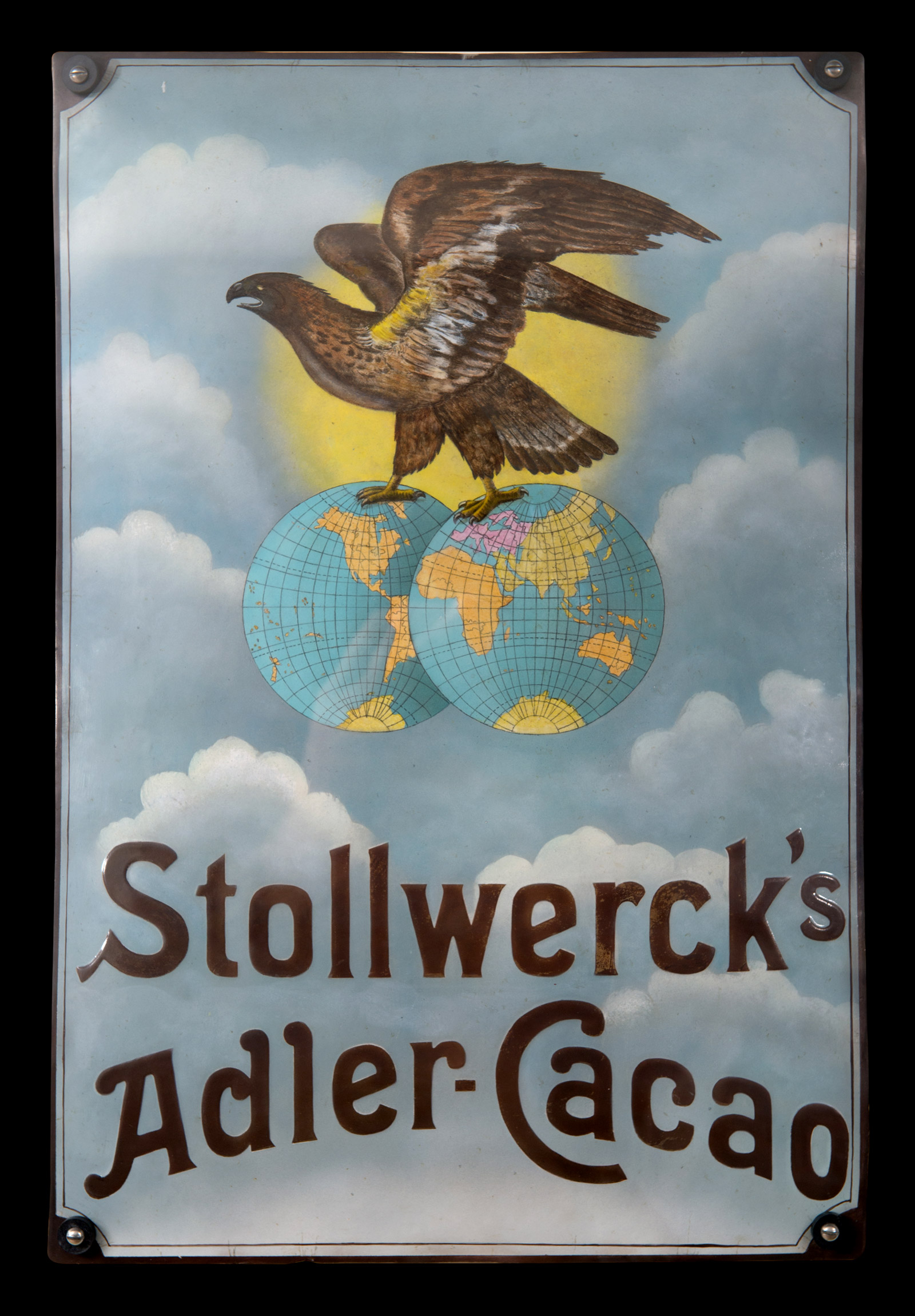

Advertisements on vitreous enamel first appeared on German streets at the end of the nineteenth century. These beginnings could be said to be sweet, in that the first person to make use of them for marketing was chocolate factory owner Ludwig Stollwerck. Historically speaking, however, fire insurance–related enamels may have had a more bitter taste associated with them, especially in the larger European context. That is because one of the primary functions of these plaques was to distinguish between those individuals whose properties were insured against fire and those who could not afford such protection.

This was particularly true in England, where a flourishing private fire insurance business had emerged in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London in 1666. Until the founding of a municipal fire brigade in the 1860s, these private insurers had agreements with various independent firefighting corps. The fire marks—made from simple brass or iron, before vitreous enamel became available—thus served as a kind of guarantee that in the case of a fire, the expenses related to extinguishing it would be reimbursed. What happened to buildings that lacked the necessary plate remains unclear. As historian Simone Ladwig-Winters has pointed out, “There is no evidence that a fire brigade that had shown up at a site would have left a house not insured by them to burn—but that doesn’t exclude the possibility.” Despite the lack of documentation, one suspects that a building without a fire mark was anything but safe.