Inventory / Flameholders

Art and engineering in the early Jet Age

Jim Moske

“Inventory” is a column that examines or presents a list, catalogue, or register.

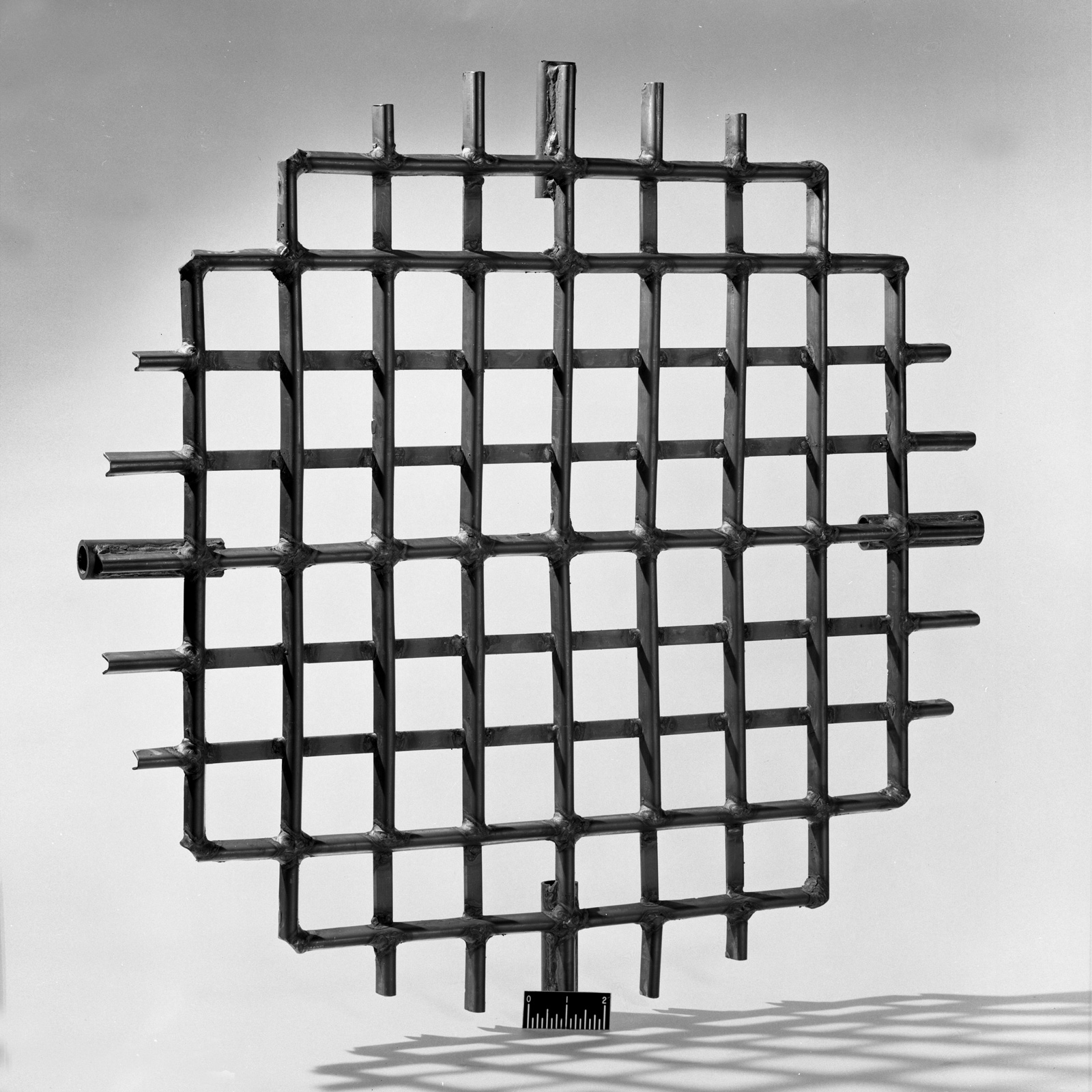

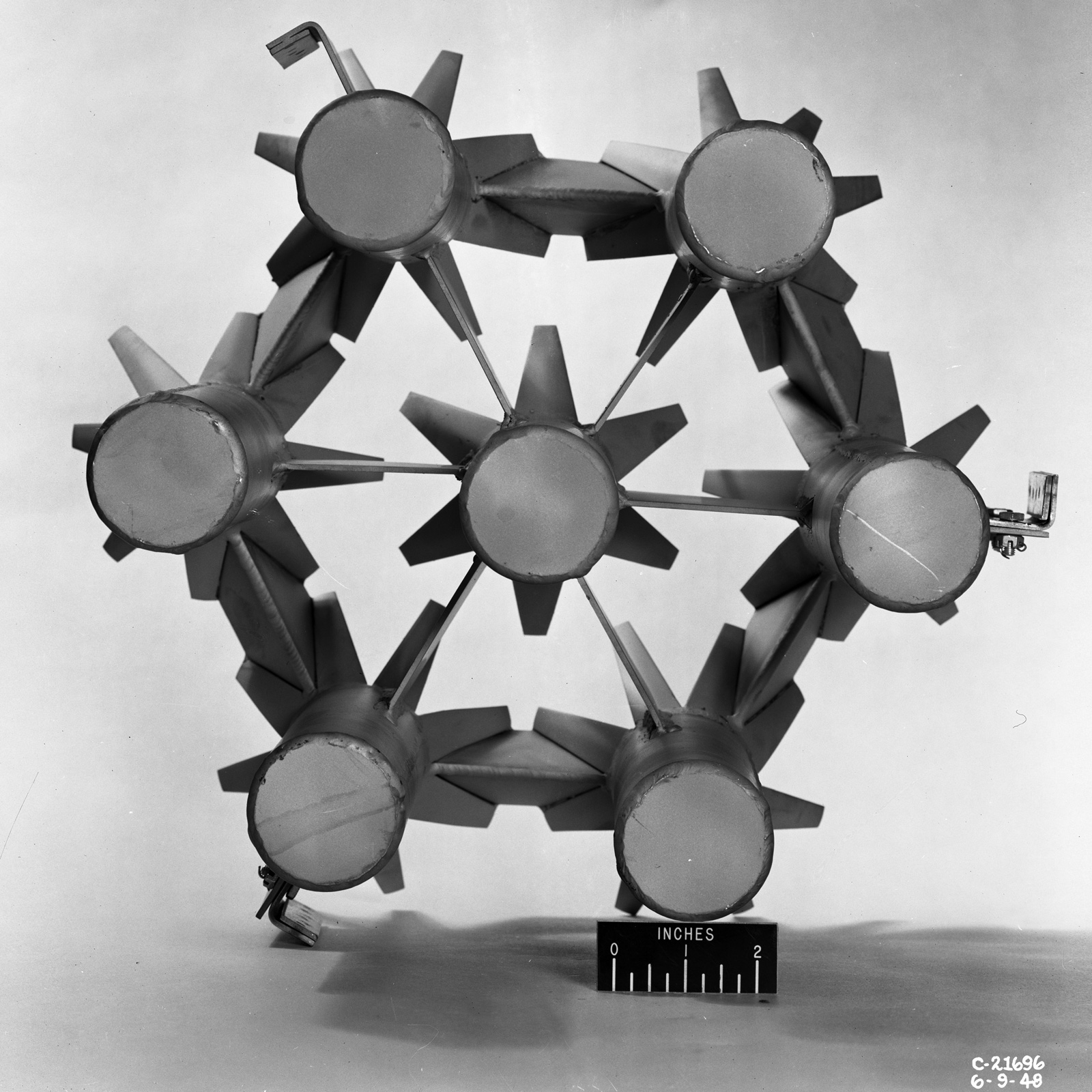

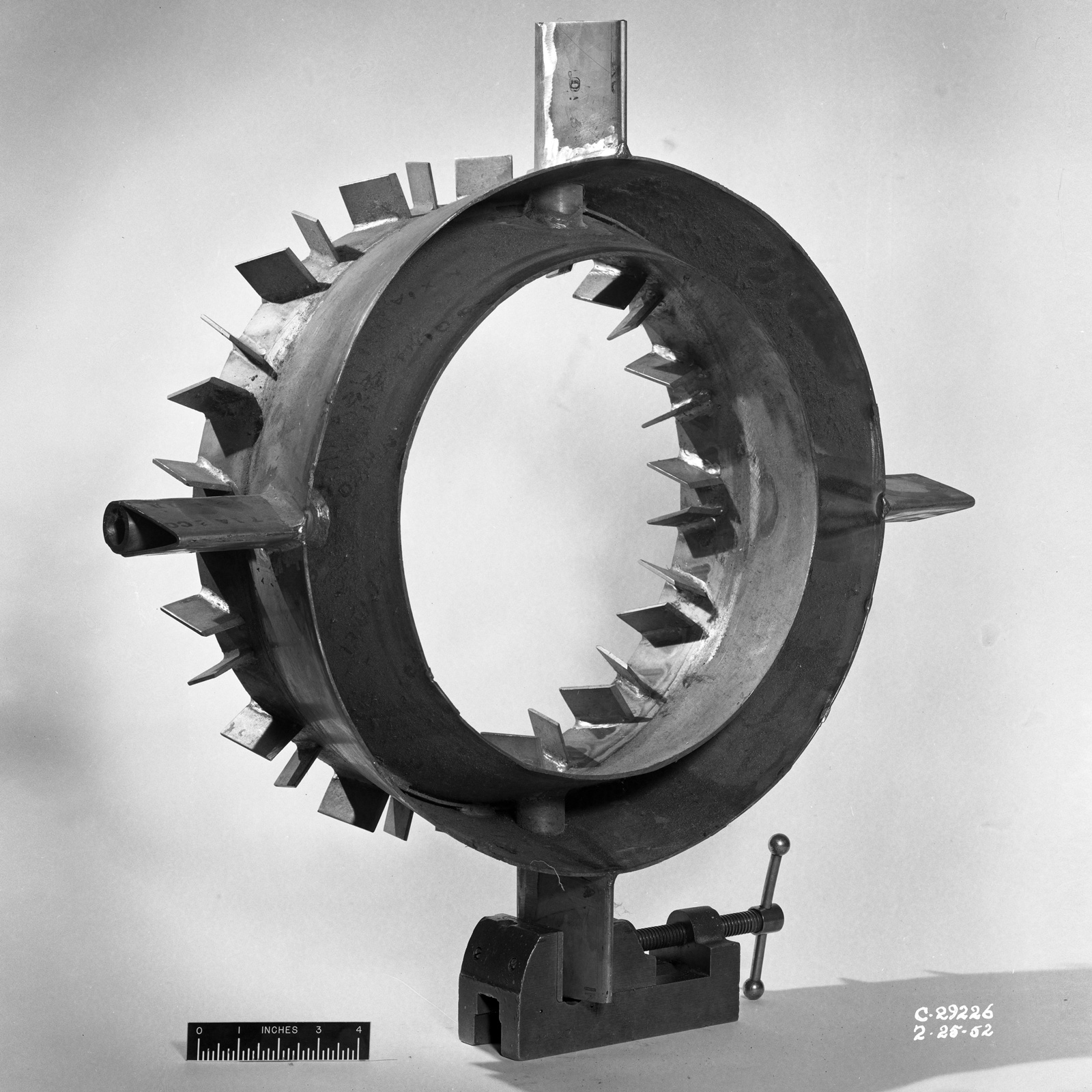

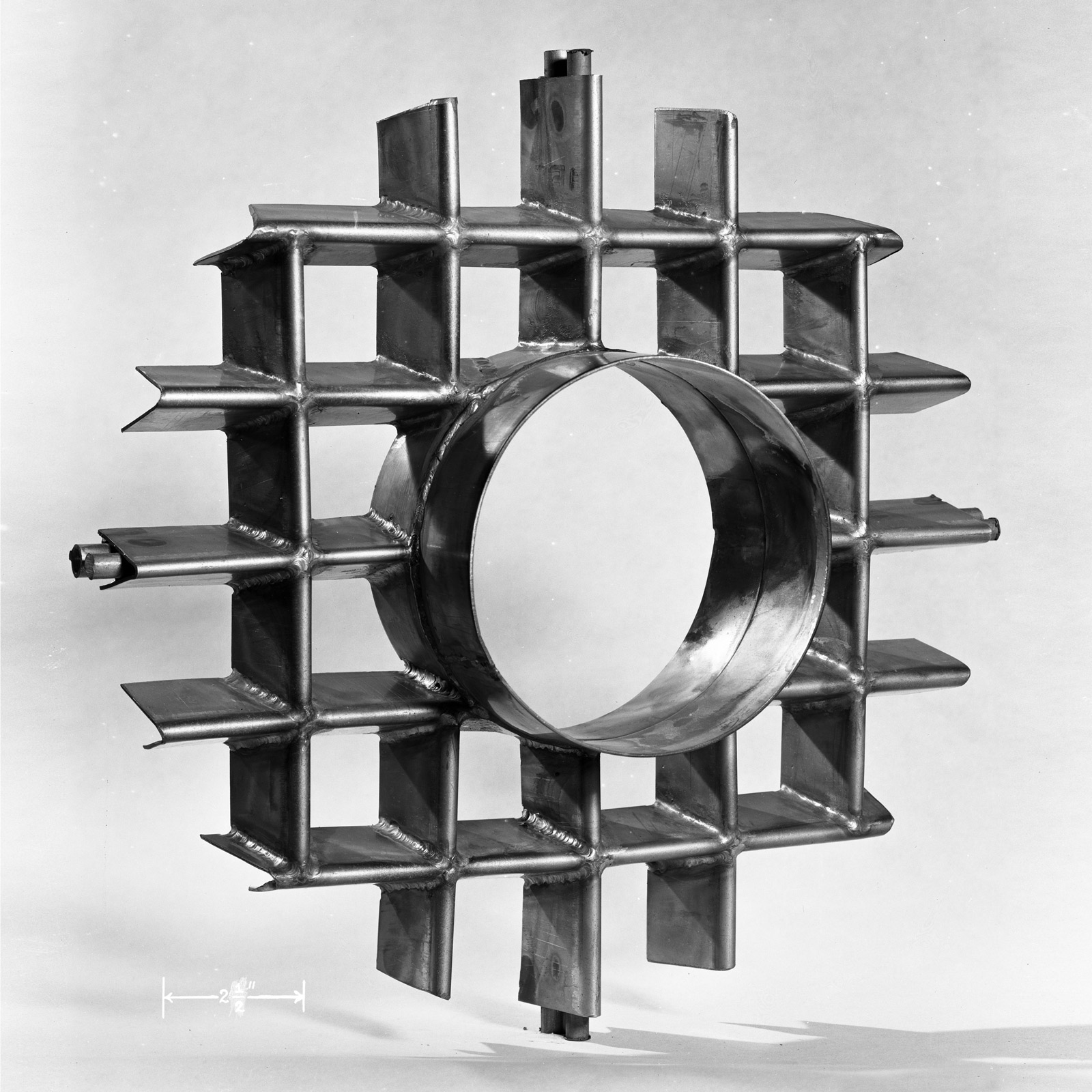

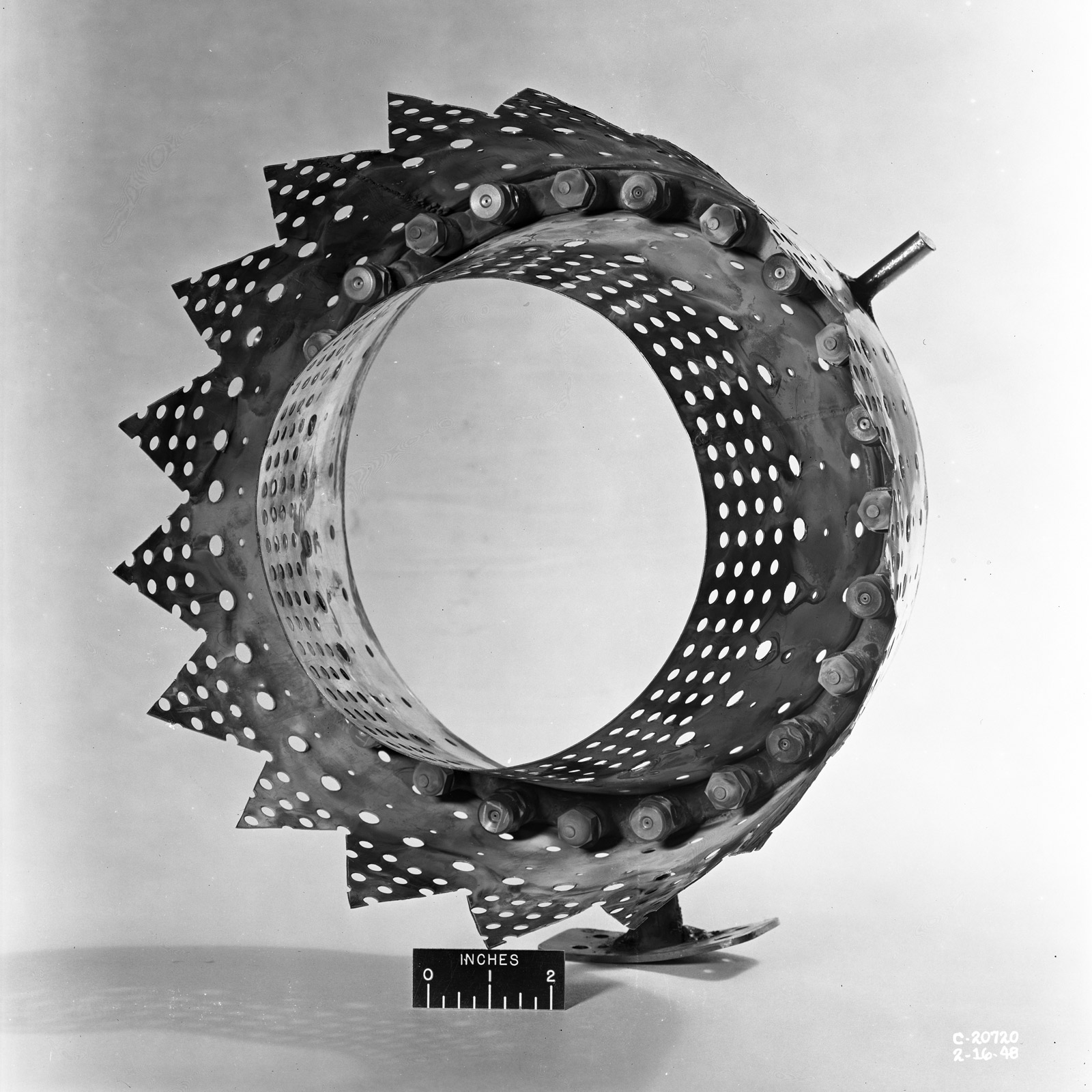

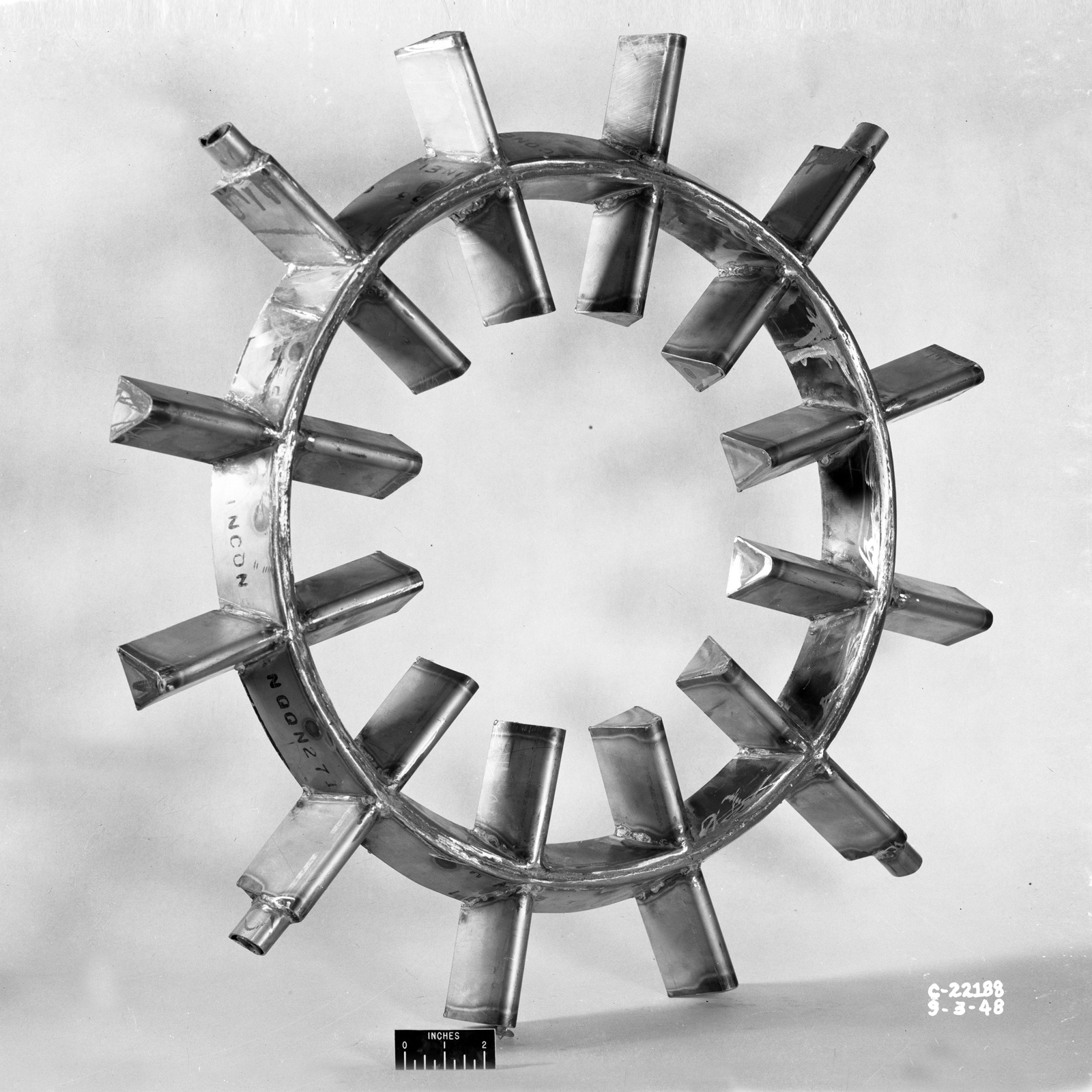

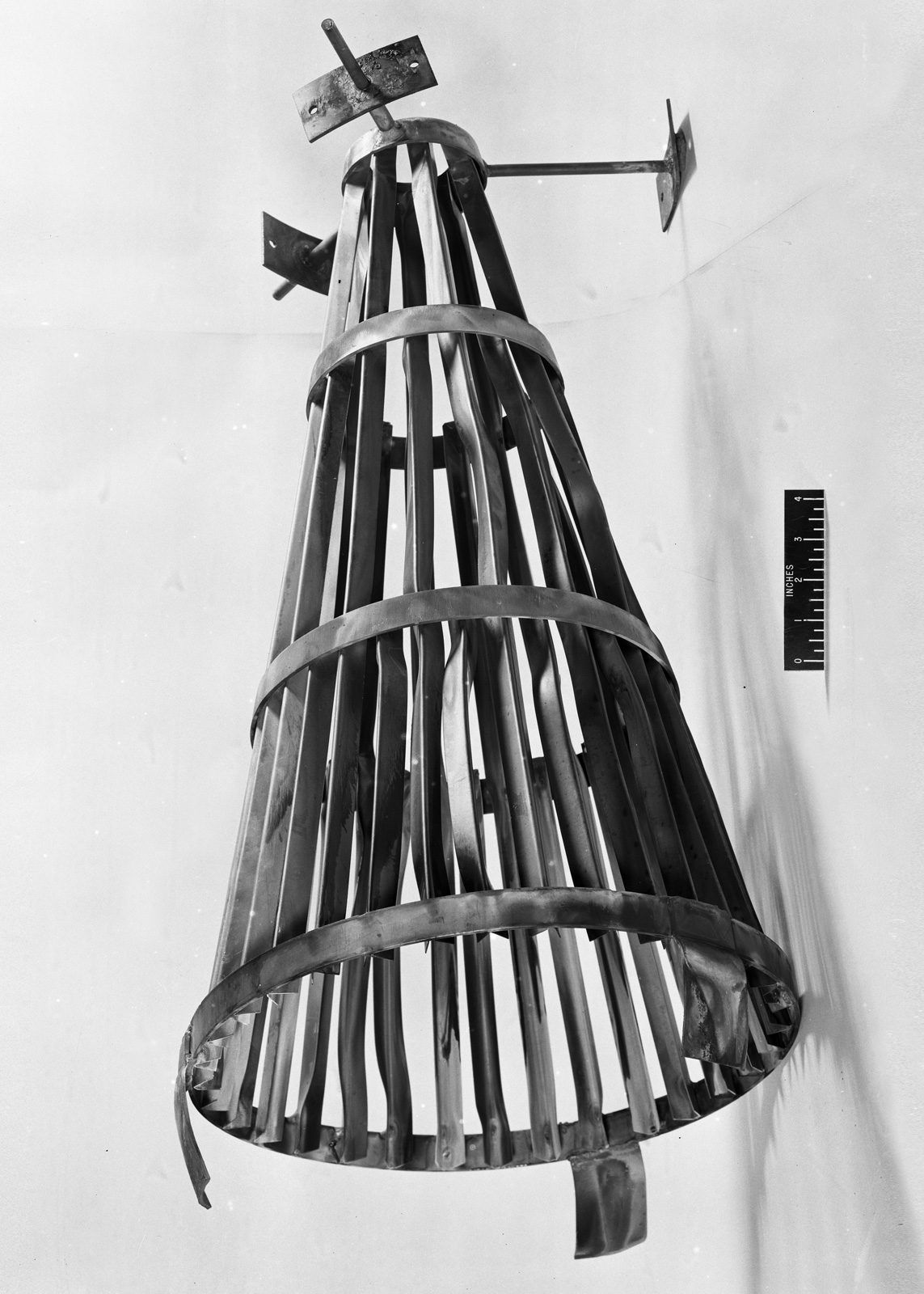

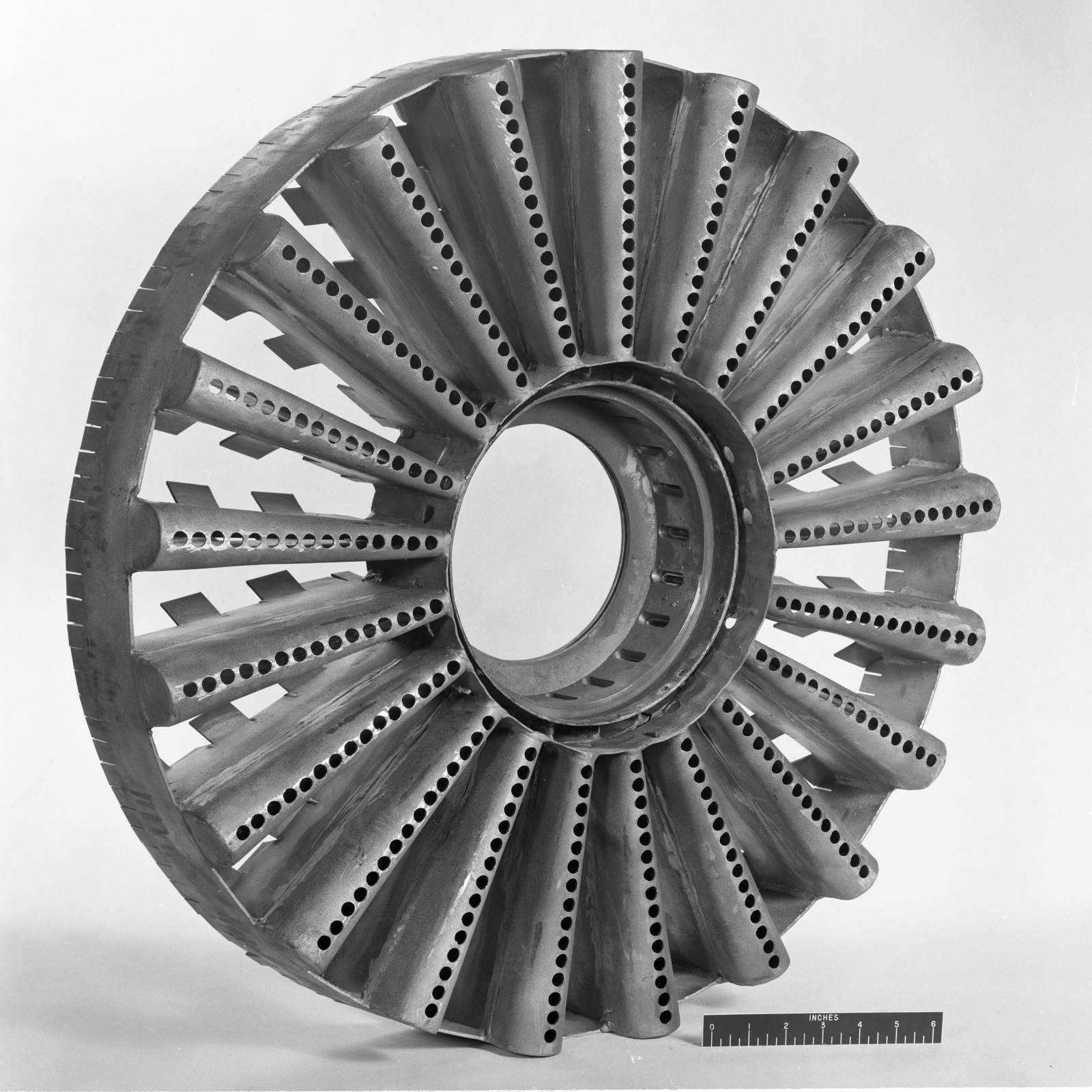

Various flameholders produced during the 1940s and 1950s. NASA records, courtesy National Archives and Records Administration.

In 1912, an imposing trio of European artists were perusing the Paris Air Show, transfixed by displays of aircraft and flight gear from the early years of human aviation. One of them, painter Fernand Léger, later recalled that his friend Marcel Duchamp voiced an unsettling insight as he pondered the nose of a plane. “It’s all over for painting. Who could better that propeller?” Duchamp then leveled a challenge at sculptor Constantin Brancusi: “Tell me, can you do that?” Brancusi remained undaunted, later declaring, “Now that’s what I call a sculpture! From now on, sculpture must be nothing less than that.” Léger believed the revelatory encounter launched Duchamp on the path to create his first “readymade,” Bicycle Wheel (1913), in which the titular symbol of human-engineered mobility was affixed upside down to a wooden stool.

This groundbreaking conceptual work, which made a case for the artistic merit of mass-produced commercial objects, would inspire others to explore the aesthetic potential of fabricated industrial forms. Brancusi, perhaps recalling the air show visit, went on to make a flock of sleek Bird in Space sculptures that resembled individual propellor blades. In 1926, US customs agents sparked controversy by denying that a Bird, en route from Brancusi’s Paris studio to New York, was art. Purchased from the artist by noted photographer Edward Steichen, the work was out on loan for the first major US exhibition of Brancusi’s work, curated by Duchamp at the prestigious Brummer Gallery. American tariff law stipulated that original sculptures or paintings could enter the United States duty-free, while most industrial and commercial manufactures were subject to a hefty import tax. After deliberating, US customs finally assigned the sculpture to the tax class of “Kitchen Utensils and Hospital Supplies” and imposed a duty equal to 40 percent of its declared value. Brancusi sued to overturn the assessment and, with help from Duchamp and collector Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, marshaled convincing testimony from prominent curators, critics, and artists. The judges cancelled the duty, ruling that Bird in Space was an ornamental artwork. The ruling conceded the existence of “a so-called new school of art, whose exponents attempt to portray abstract ideas rather than to imitate natural objects.” Meanwhile, “new school” exponent and Little Review editor Jane Heap collaborated with Duchamp, Man Ray, and Alexander Archipenko to stage the 1927 Machine-Age Exposition, which presented sculptures and drawings alongside assuredly dutiable products of industry, including a marine propellor and an entire aircraft engine.

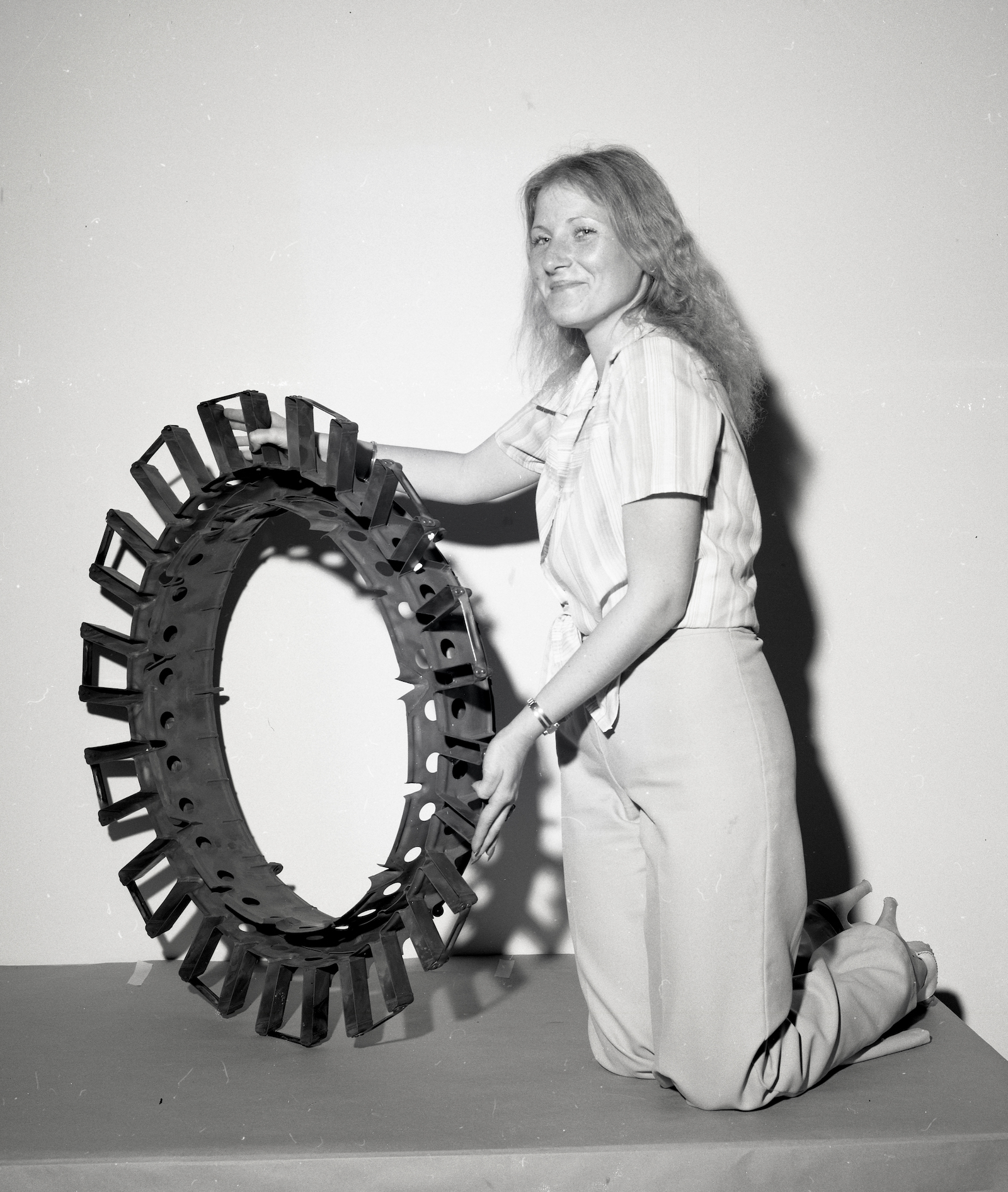

Decades later, a little-known photographer at the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) made an image that playfully explored the visual appeal of the inner workings of a new generation of jet-powered aircraft. Donald Huebler’s “Partial Flameholder” (1979) shows a woman kneeling on a low platform, propping a circular metal object on its edge with both hands. She wears a striped blouse, light-colored pants, and high-heeled shoes. It is one of thousands of documentary photographs of jet engine parts shot in the mid-twentieth century at the research facilities of NASA and its precursor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA).

It was the task of scientists at these agencies to enhance the performance of engines built by General Electric, Westinghouse, and Pratt & Whitney, ushering in the age of commercial jet travel and assuring American military superiority in the sky. Inside a jet engine, ultra-hot compressed air blasts through the tubular barrel of the machine and ignites a spray of fossil fuel. Ironically, the scorching wind that sparks the flame also threatens to snuff it out. This was a vexing problem that NACA and NASA technicians addressed by refining the design of a component known as a flameholder. This heat-resistant device disrupts the rush of wind through the engine and creates eddies of stable air that allow the fire to burn steadily, preventing the machine from stalling out. Flameholders crafted in early phases of testing were festooned with fingerlike appendages, hole-punctured flanges, or waffled grids improvised as windbreaks.

Photographers supported the research team by systematically recording the appearance of flameholders before and after use. They churned out tightly framed black-and-white images of their subjects isolated against clean backgrounds. Donald Huebler’s 1979 picture with a female model was an unusual, late entry in the series, which mostly dates from the 1940s and 1950s. There is no clue in the archival metadata about the woman’s identity or what she had to do with jet engine research. Her sidelong glance and subtle smile infuse the scene with a sense of double entendre, compelling closer scrutiny of the rest of the flameholder photos.

It is easy to imagine that these assorted objects were fashioned not by aeronautical engineers but instead by artists inspired to create whimsical variations on organic shapes, such as flowers, diatoms, or cyclopean heads. The staging of the flameholders against neutral grey backdrops mimics an approach museum photographers of the day employed to present sculptures to best advantage and inspires contemplation of their curious forms from a purely aesthetic perspective.

Abstracted from the jet’s whooshing core and held steady for the camera by a bench vice—or a smiling woman—the contraptions in these pictures look impish and monstrous, like biomorphic remixes of robot parts patched together by Dada-inspired sculptors. Duchamp’s inscrutable readymade Bottle Rack (1914), a prefabricated item purchased from a department store and declared art with no further tinkering, offers a remarkable visual parallel to a 1948 basket-shaped flameholder, photographed by Bill Bowles. Both look well suited to keep the fire burning in a vintage General Electric J35 jet engine.

There is no telling if Bowles or Donald Huebler were aware of the specific visual precedent of Duchamp. But clearly, the once-radical insight that machines hold aesthetic value had been thoroughly absorbed by this cohort of twentieth-century image-makers embedded deep in the military-industrial complex. Huebler produced thousands of images of aircraft and spacecraft components, NASA facilities, and staff in a career that spanned the pioneering era of space exploration from the 1960s to 1980s. Many of his pictures are distinguished by self-conscious artistry and sly humor—though just as many look mass-produced to meet bureaucratic imperatives and seem more fitting for advertising brochures than fine art catalogues.

A few photographs by Huebler carry a hint of eroticism and feature other female models suggestively posed with plane parts or spacecraft, echoing 1970s sales pitches for automobiles that objectified women in the hopes of stimulating vehicle sales. “ASTP Model” (1974) shows a kneeling woman wearing pumps and a short skirt or dress cradling a plaque-mounted representation of conjoined American and Russian space capsules, a pioneering feat accomplished in orbit one year later during the Apollo-Soyuz mission. A full-scale model of the linked spacecraft is now installed in the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, which also holds in storage 1940s and 1950s jet engines complete with flameholders like those recorded in the photo archive.

Most flameholders, after completing their test missions and submitting to documentary imaging, were not accessioned by museums. They were consigned instead to the scrap heap, akin to how several Duchamp readymades were lost or discarded not long after their debuts. Many of us have come to know these objects only through photography. “The choice of readymades is always based on visual indifference,” the artist explained to historian Pierre Cabanne, hinting at his intuition that the physical works were less interesting than the radical reframing that deemed them art in the first place. Donald Huebler and his colleagues may have been steered by bureaucratic imperatives to catalogue a large inventory of castoff engine parts, but their images manage to preserve the stark beauty of this detritus from the Jet Age. Who, someone might one day ask, could better those flameholders?

Jim Moske is an archivist and author based in Hamilton, Ontario. He was managing archivist of the Metropolitan Museum of Art for fifteen years and, prior to that, archivist of the New York Public Library. He is the author of Deaths of Artists: From the Archives of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Blast Books, 2024).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.