On the Wire above the Ruins

Funambulism in postwar Germany

Yuliya Komska

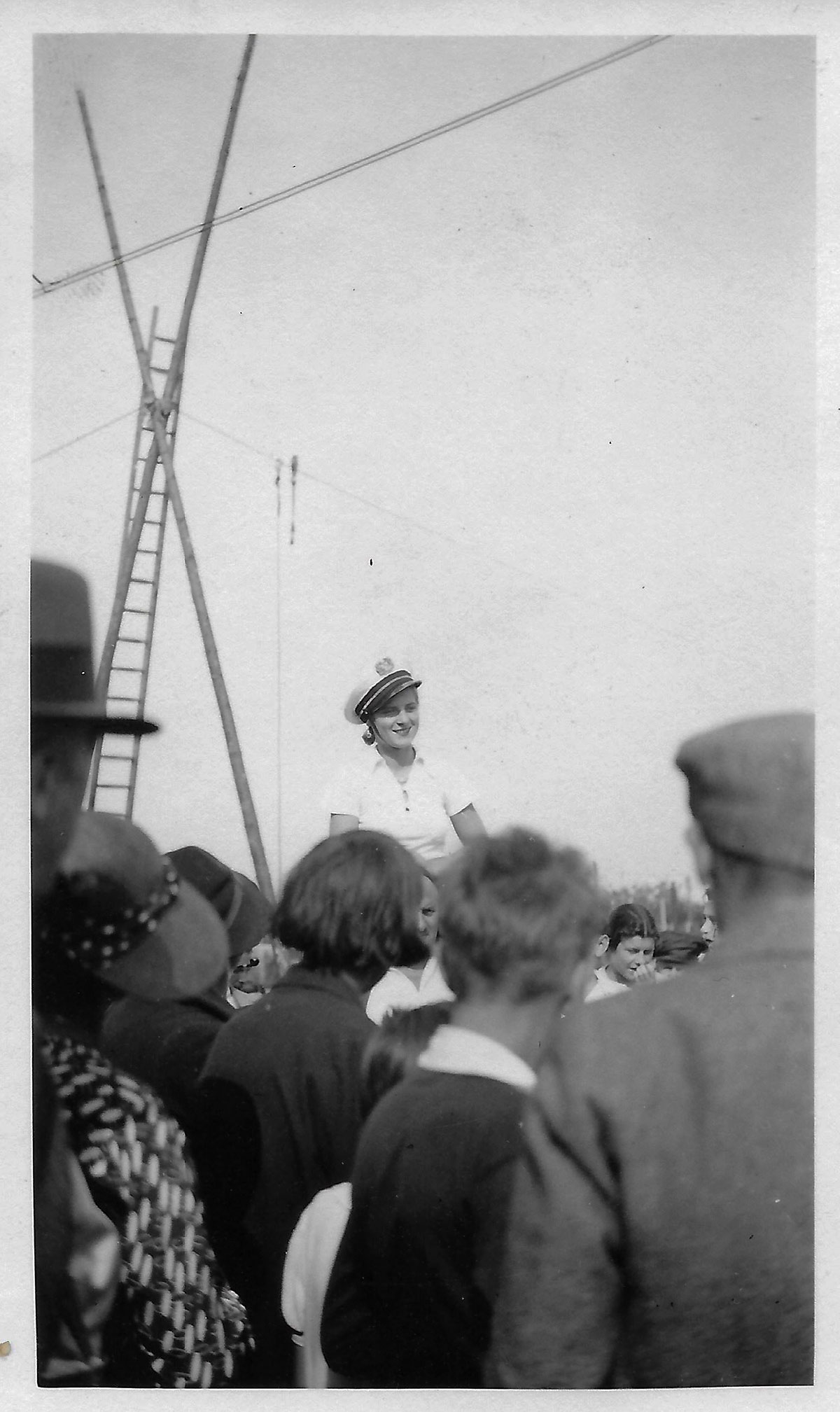

A dab of lipstick. Blondish victory rolls, deflated from exertion and wind and the gravity of defeat—the wartime German colloquialism describing the hairstyle, Entwarnungsfrisur, or “all-clear hair,” might be more apt here. Her clothes, by contrast, are flawless. A short-sleeved shirt, prim and neat, is tucked into dark hotpants. Over that, a gauzy white pinafore billows in the wind, baring the long, strong legs. A token pinup riff on the naughty schoolgirl look. Or, in the eye of lyrical upskirter Max Frisch, “a Degas seen from below.”[1]

Neither curvaceous nor frothy enough to be either, she carefully places her right foot in front of the left, staring fixedly ahead, in the direction of the camera. Never below, that would be deadly; there’s no lifeline or safety net. Up and up, her soles hug the curve of the tightrope. It’s the riskier type known as the slack rope, which, in a reporter’s description, “buckles, sways, and swings” unpredictably.[2] The elevation is vertiginous; passersby look the size of carpenter ants. How much higher? The snapshot leaves us speculating. Maybe she will stop and rest on the tiny platform where the photographer is perched. Maybe she, the wingless Nike of surrendered Germany, will dance on skyward—in German, one dances on the wire. Or maybe she will trip and crash, like the tightrope walker in Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra. “Thou hast made danger thy calling; therein lies nothing contemptible,” Zarathustra consoles the dying acrobat. “Now thou perishest by thy calling: therefore I will bury thee with mine own hands.”[3] Except it’s Germany in 1946, and to die—even “a good death, an individual death, a death of one’s own,” the luxuries of which Frisch (being Swiss) pondered while watching a similar act—and be buried by a stranger would be the coldest of comforts.[4]

Inescapable is the funambulist’s balancing pole, heavy and long, which runs across the entire photo. With a single stroke, it seems to abolish the charred, filthy ruins of a bombed-out market square beneath. Façades without interiors, belltowers without churches, windows without glass, avenues without trees: as long as the woman is up on the wire, they don’t exist, either for her or for the spectators down below. Those huddle and peer into the heights, not to look out for bombers (a wartime tick) but to glimpse transcendence, to forget about the sprawl of the rubble and the oppressively horizontal voids, called “the steppes,” among it. Even if briefly.

• • •

When the photo was published several years ago, first in a book, people rushed to identify its subject. One reader, a trapeze artist from the famous Traber clan in Stuttgart, claimed to recognize his cousin, Rosanna.[5] His suggestion was plausible—since acrobats frequently come from multi-generational dynasties of “privates,” to use old professional slang—but incorrect. A historical witness, fourteen years old in 1946, shared as much with a reporter.[6] As proof, she proffered two postcards acquired on that market square in Cologne in those days. One of them identified the intrepid performer as Margret (Margarethe) Zimmermann, of the internationally famous Camilla Mayer Troupe.

Aside from Herr Traber’s disappointment, the exchange revealed the glut of young acrobats willing to put life on the line above the rubble of postwar Germany. Each troupe typically trained several dozen at once; the Camilla Mayer Troupe featured over twenty on their programs. Many had little to lose, having come from Pomerania, Silesia, Bačka—the traditional strongholds of the trade and, coincidentally, the areas of liberated eastern Europe where ethnic Germans were no longer welcome. The postwar expulsions had smashed their lives to smithereens, and they found themselves homeless, destitute, sometimes orphaned, and desperate for balance and stability.

Oddly, the wire over the ruins offered them greater balance and stability than almost anything else. Or was that really so odd? Attraction to perilous landscapes in times of upheaval, historian Tait Keller records, has deep roots.[7] Such places promise us something eternal, something removed from the world’s vanities, something immaterial and din-free. Perhaps that was how the postwar funambulists felt, levitating over the firebombed cities like angels in a Wim Wenders film. Or perhaps, conversely, they were hard-boiled realists, and the wire was simply the surest path toward material security. “Extraordinary what people will do in order to live,” Frisch marveled at the sight of a ten-year-old swaying thirty meters above the ground.[8]

• • •

“Man is a rope stretched between the animal and the Superman—a rope over an abyss,” Nietzsche’s Zarathustra declared in 1885.[9] In 1946, both the abyss and the figurative tightrope walker’s task could not have looked more different. The Superman fantasy, for one, had gone bust. As for the abyss, writer Alfred Andersch noted, it now spilled between the disgraced Germany and the rest of Europe. Someday—Andersch reached for a hopeful metaphor—a few courageous tightrope walkers would bridge it, seeding unity.[10] Meantime, Germans would have to make do with real-life funambulists. These people would provide popular, affordable, and uncensored mass entertainment, much cheaper than the movies.[11] But their work would not be all bread and circuses: it would offer a foil for the fragile relationships Germans were forging with the past, the present, and the future.

To grasp the lure of funambulism over the ruins, consider that verticality typically occupies two dimensions: depth and height, underground and above ground, mineshaft and mountain, as historian Patrick Anthony puts it.[12] The German Romantics made much of their inextricability. Many had studied mining, while others oversaw the operation of mines. Some, like Alexander von Humboldt, also traveled the world to learn from the Indigenes about what scholars today call “vertical consciousness.” Admittedly, the Romantic fairy tales about ascents and descents didn’t always honor such empiricism. Critic Theodore Ziolkowski once observed how in these fictions, science often paled in the sheen of precious metals, hard-edged crystals, and subterranean maidens.[13] The flourishes notwithstanding, the maxim remained: there could be no surface without the depth. Yes, the fairy-tale peaks did entice with revelations and mystical communions. But only the mine, this proverbial site of plunder, could stage the unavoidable “moral ordeal” and test the protagonists’ integrity with the corruptive forces of avarice and lechery. Only in the mine did the inescapable confrontation with one’s self and history await.

The physical as well as moral geography of funambulism lacked the underground dimension. There was no depth, no mine, no face-off with self or history—only the escape upward or the curse of the ground. Those who could not rise ended up falling to their deaths. Rosanna Traber did at some point in 1947. Josef Eisemann and his teenage daughter Rosa, poised to repeat their crossing of the Danube Canal in Vienna, did in 1949. As the bodies hit the ground—with a hushed, “dull thud in the rubble,” Frisch imagined, like small birds shot down on a hunt—and the floodlights went out, hundreds of screams pierced the darkness.[14]

In the mid-1950s, the Swiss psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger would sound the alarm about the psychological side effects of clambering higher and higher. He named the condition Verstiegenheit, which his English translator rendered as “Extravagance” (from extra, “beyond,” and vagari, “to wander”), although it comes from steigen, “to climb.”[15] Verstiegenheit was no simple haughtiness but rather a set of manias and neuroses that stemmed from a “disharmony between rising upward and striding forth.” With all the energies funneled toward the top, in other words, there was no broadening of conscience or of intellect, no “occupying [of] the world.” The task of the psychiatrist, in Binswanger’s mind, was to “bring the patient safely back ‘down to earth.’”

Funambulism was no pathology, but Binswanger’s musings point to the trade’s inherent ambivalence against the backdrop of postwar Germany. Was rising above the ruins a tacit refusal to “occupy the world,” with body or with knowledge, like Germans had done in recent history? Or did it, conversely, signal the stubborn persistence of the Übermensch dream? Was it a sign of humility? Of hubris? Of something else?

More confusingly still, there was the question of the difference between the audiences’ looking up and looking away. Were they identical? “People’s ability to forget what they do not want to know, to overlook what is before their eyes, was seldom put to the test better than in Germany of that time,” W. G. Sebald famously wrote.[16] The averted gazes, the shielded eyes, the staring without seeing defined the postwar everyday. The Allied confrontation campaigns, which aimed to rouse contrition and responsibility by driving hundreds of German civilians to the local Nazi killing sites, quickly ran aground on these defense mechanisms. Avoidance extended to other traces of destruction. In 1950, Hannah Arendt despaired at the sight of Germans exchanging picture postcards with the views that the war had long bombed out of existence.[17] She read them as a symptom of the numbness with which her onetime compatriots responded—or rather, failed to respond—to what their own deeds had wrought.

But whereas looking away offered no redemption, only repression, looking up was an ongoing experiment in rise and rebirth. Of this, the Camilla Mayer Troupe was a shining example.

• • •

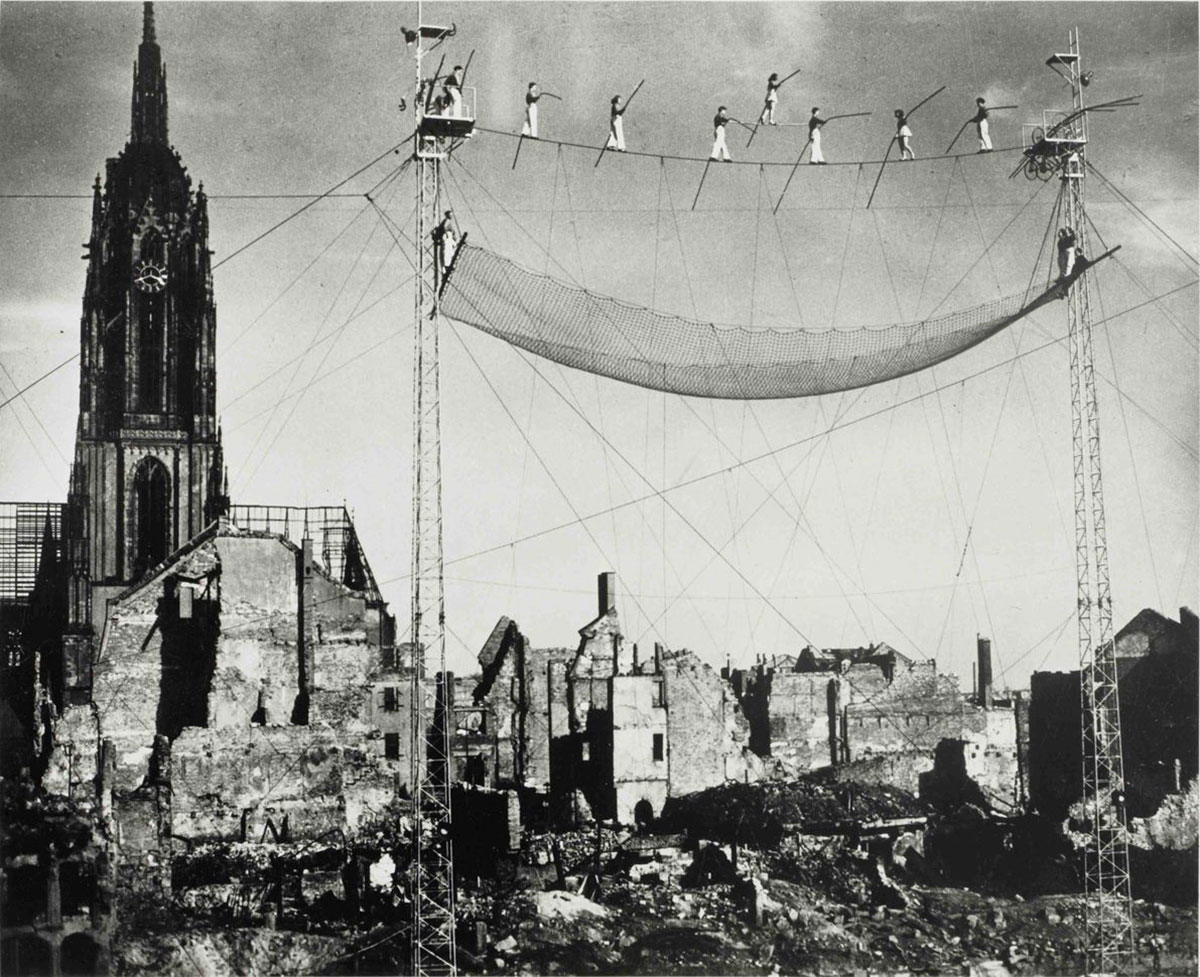

The troupe got around in those years. In 1946, it mustered a week-long series of nightly ninety-minute-long shows to benefit the reconstruction of Leipzig in eastern Germany. In 1947, it turned up in Berlin’s Lustgarten, across from the Hohenzollerns’ palatial detritus, with one Manfred Ziegler in a guest cameo. A known high diver and former pilot in Hitler’s Luftwaffe (but a tightrope rookie), Ziegler didn’t die, which counted as good publicity for the troupe and helped bolster his Luftwaffe credentials. In 1948, the acrobats appeared on Nuremberg’s Main Market Square; Anthony Vaccaro, an American GI and perhaps the most perceptive photo-chronicler of occupied Germany, snapped their picture in Frankfurt am Main. Vaccaro attended a daytime performance, whereas Max Frisch got himself a ticket for one after dusk, when the “ruins and Gothic architecture transformed into a vast show, half bar, half fairground,” incongruous and commonplace at once.[18] That same year, a newsreel segment titled “Menschen zwischen Himmel und Erde” (People between heaven and earth) profiled the Traber and the Mayer troupes at work, celebrating their “artistic brilliance.”

When the film singled out a headstand artist as a young mother, the camera panned to her toddler snacking on an apple in the window of a trailer nearby. This was to say: strung onto ropes like misshapen beads was no fahrendes Volk—a derogatory term for circus performers and vagabonds—but reputable tradespeople and dutiful reproductive and reconstructive citizens.

The many surviving visuals reflect not only the full palette of “breakneck artistry”: the walking seven-person pyramids; the forward and backward unicycle, bicycle, and motorcycle rides; the pole headstands; the somersaults; the nerve-racking lone “death walks.” They also highlight the audiences’ awe. Young and old, people sit in orderly rows, heads raised at identical angles, eyes bewitched. Until suddenly one jumps up from his seat, another opens her mouth in suspense and astonishment, and these individual reactions make the flashback to synchronized Nazi ceremonials dissipate to the sounds of a circus march. Minute by minute, the spectacles’ charms soften the stiff-lipped onlookers, kneading them into sentimental clay. Only a young Black American GI, sitting next to Frisch in April 1948, appears unimpressed. Without clapping, “he gropes in his top pocket, takes out a cigarette, which he places in his mouth….”[19] Frisch’s ellipsis hints at a multitude of contradictory feelings, unexpressed and unresolved.

The settings spellbind no less than the acts. They are similar across cities: central market-square locations, like in olden days, with ample ambient ruins and virile yet gaunt metal masts erected to hold the ropes and the wires. The masts resemble radio transmission towers and rise steeply toward the heavens, as if to broadcast something in defiance of the Allies. (Occupied Germany had no sovereignty over the airwaves.) Their skeletons are visible from afar, and at dusk, on long spring and summer evenings, they cast dramatic, angular shadows worthy of Dr. Mabuse. Frisch fell hard for their spectral magic. It reminded him of a shipwreck, “sunk not beneath the waves of the sea, but beneath waves of rubble, weed-covered brick.”[20] When “the ruins are spotlighted,” he wrote, “everything looks even more like a fairyland; a milky light spreading out into greenish darkness, in it an occasional gleaming moth, and behind the glittering trapeze one sees the cathedral, a flat outline, a silhouette, a weightless pallor of red sandstone standing disembodied behind a cagework of crossing searchlight beams.” At a distance, Frisch could hear the shovels of builders working late to reconstruct the air-raid-pummeled St. Paul’s Church: the emblem of democracy was set to reopen for the centennial of the German National Assembly. The sound of trapeze wire, sharp like “the tearing of silk,” and the monotonous shovel scraping melded into a dissonant score of postwar desire—an anthem if ever there was one.

But sometimes, the wire stretches between buildings, though sturdy structures are scarcer than hen’s teeth. City centers are no longer made up of streets and squares ribboned with quaint houses. In many places, there’s a hint of a stepped gable here, a bomb crater there. Heaps of rubble tower all over, pulverized but not flattened, to paraphrase journalist Isaac Deutscher. Every day, the “rubble women,”—that is, most able-bodied women—come out to clean whatever can be salvaged. The rest is buried in mounds with telltale names—Monte Scherbelino (Mount Little Shard), Mont Klamott (Rag Mountain)—to raise the country “above the psychosis of the rubble,” in the words of urbanist Hans Bernhard Reichow.[21] A thin layer of dirt dusts these new elevations. The gritty ruderal species color them green. The ruin starts looking a lot like renewal.

• • •

It is no accident that funambulism thrived on this ambivalence between nature and culture, on the ability to reimagine the toothy, jagged skylines as latter-day mountain ridges, on the remaking of landscapes. Edging Alpinism out of public imagination, temporarily, wasn’t overly difficult. The destroyed railways and highways rendered many natural elevations inaccessible. The sport itself had been compromised by the Nazis (Hitler loved the Alps and, as scholar Caroline Schaumann points out, bought his Obersalzberg retreat with the royalties from Mein Kampf) and steeped in nineteenth-century racial science and the cult of the white male body going to fanatical extremes.[22] The old ideal hung by a thread now that masculinity lay in shambles.

In postwar “rubble films,” ascending the ruin, rockfall and all, is a common motif and a symbol of the struggle to restore old-school manliness. Unlike Weimar-era “mountain films,” where the dangerous journey upward is ultimately the grown man’s dubious privilege, here the task often falls to fatherless boys. They are often portrayed as an offputtingly ineducable lot, defiant of the laws and claws of patriarchy.[23] Like the ruins in which they feel too comfortable, the youths must be condemned to destruction—a sacrifice for rebirth’s sake. And so the boys ascend. Gerhard Lamprecht’s Somewhere in Berlin (1946) is memorable for its agonizing scene with orphan Willi’s climb of and tumble from a peak-like façade. The final scene in Roberto Rossellini’s Germany, Year Zero (1948) tantalizes with the erratic hops and slides of little Edmund (his own father’s clandestine poisoner) inside a multistory building skeleton before he throws himself downward. There’s no chance of his resurrection, only a ritualized pan up another ruin.

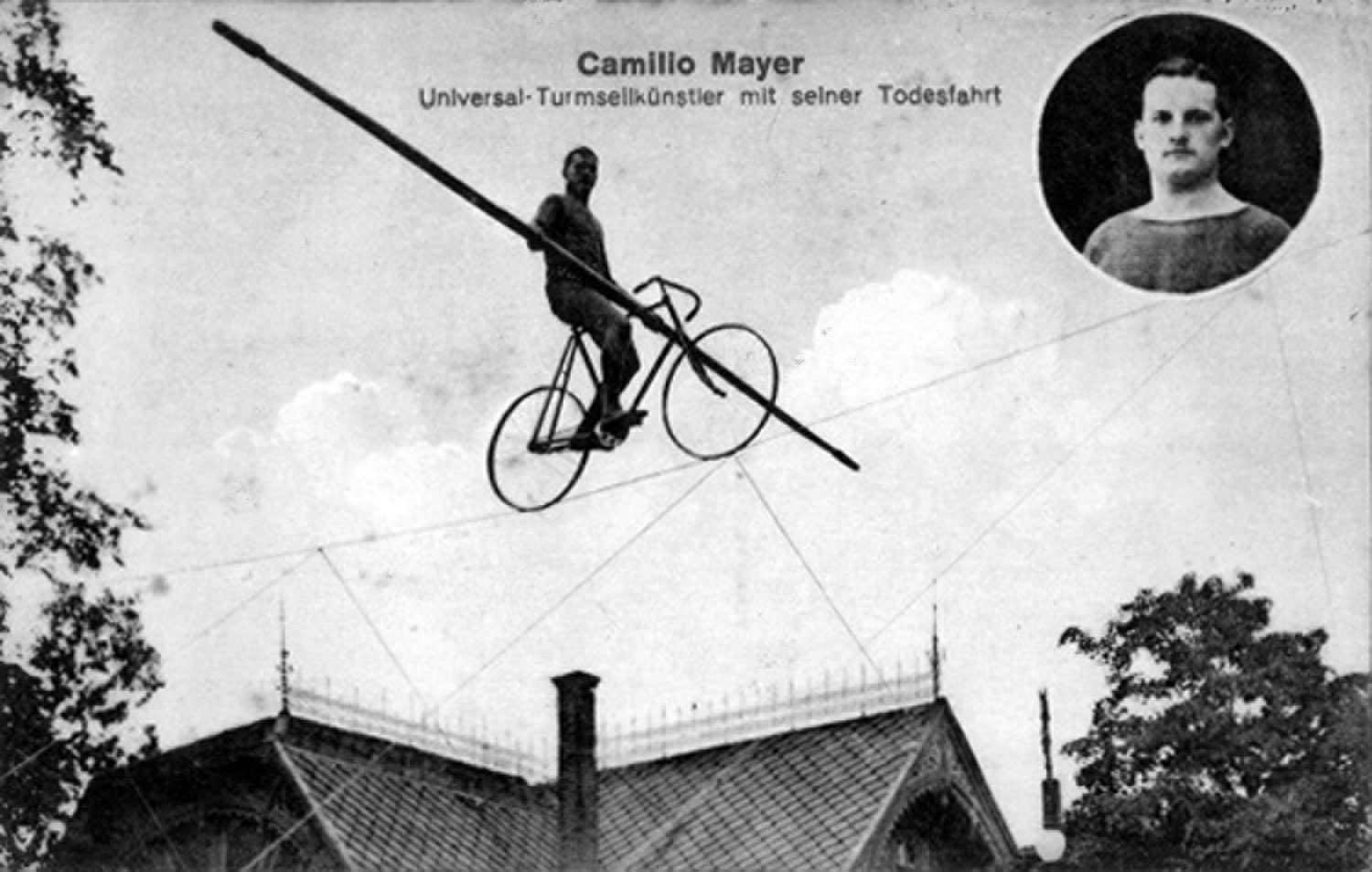

By contrast, the Camilla Mayer Troupe stands out for its ability to project a phoenix-like presence, to be endlessly reborn and redeemed thanks to its forever-young avatar whose longevity is predicated on female disposability. There were no fewer than five Camillas. The original was the daughter of the Alsatian acrobat Camilio Mayer and a German mother.[24] If we are to believe the sources, which can be scant and unreliable, as a teen she began performing in her father’s troupe, lending it her name, though it is unclear how long she lasted in this role. By 1934, she was overshadowed by one Charlotte Witte, a sixteen-year-old from Stettin, now Szeczin in Poland. Charlotte took the name and the place of Camilio’s biological daughter, turning Camilla Mayer into a signifier of aerial prowess or, in current parlance, a brand.[25] This relatively common circus practice would prove gruesomely useful after Charlotte’s deadly fall during a performance in early 1940. Three more Camillas followed: Ruth Hempel, Ruth Barwinske, and Annemarie Füldner, who, at some point, married Camilio. In a flash of angry anagnorisis that occurred in 1948, the original Camilla attempted to put an end to this Greek drama by suing the troupe for the right to her name.

The court case, publicized by the likes of Billboard, exposed the details of the troupe’s own rebirths and self-reinventions.[26] The collective allegedly performed under the leadership of Camilio until 1941, when he was arrested by the Gestapo on unclear charges and sentenced to three years in jail. In his absence, Hans Zimmer, a journalist who had found cover in the troupe after his own Gestapo arrest earlier (he may have been Jewish), took over the reins.[27] Some say he moved the troupe to Breslau, today Wrocław in Poland, where it performed until it was banned by the Nazis in 1943.

Released by 1945, Camilio soon signed up to entertain the Soviet officers’ wives in east Germany.[28] They liked him well enough to pay in tobacco—over time, a whopping 10,000 cigarettes. This hardest of postwar currencies became his starting capital. The venture was simple: to oust Zimmer and consolidate the troupe. It worked, though it took years and brought only modest financial success. After stints in London and Paris, Camilio eventually scored the coveted contract to tour the United States with the Ringling Brothers. A 1953 issue of Popular Mechanics gave the troupe rave reviews, delighting at the stunt with a female wire biker and her 150-pound “bomb.” “The bomb explodes, pulling the bicycle over and under the wire,” the journalist gushed, ignoring the literalness of this “bombshell” in a world where new weapons assured future ruins galore.[29]

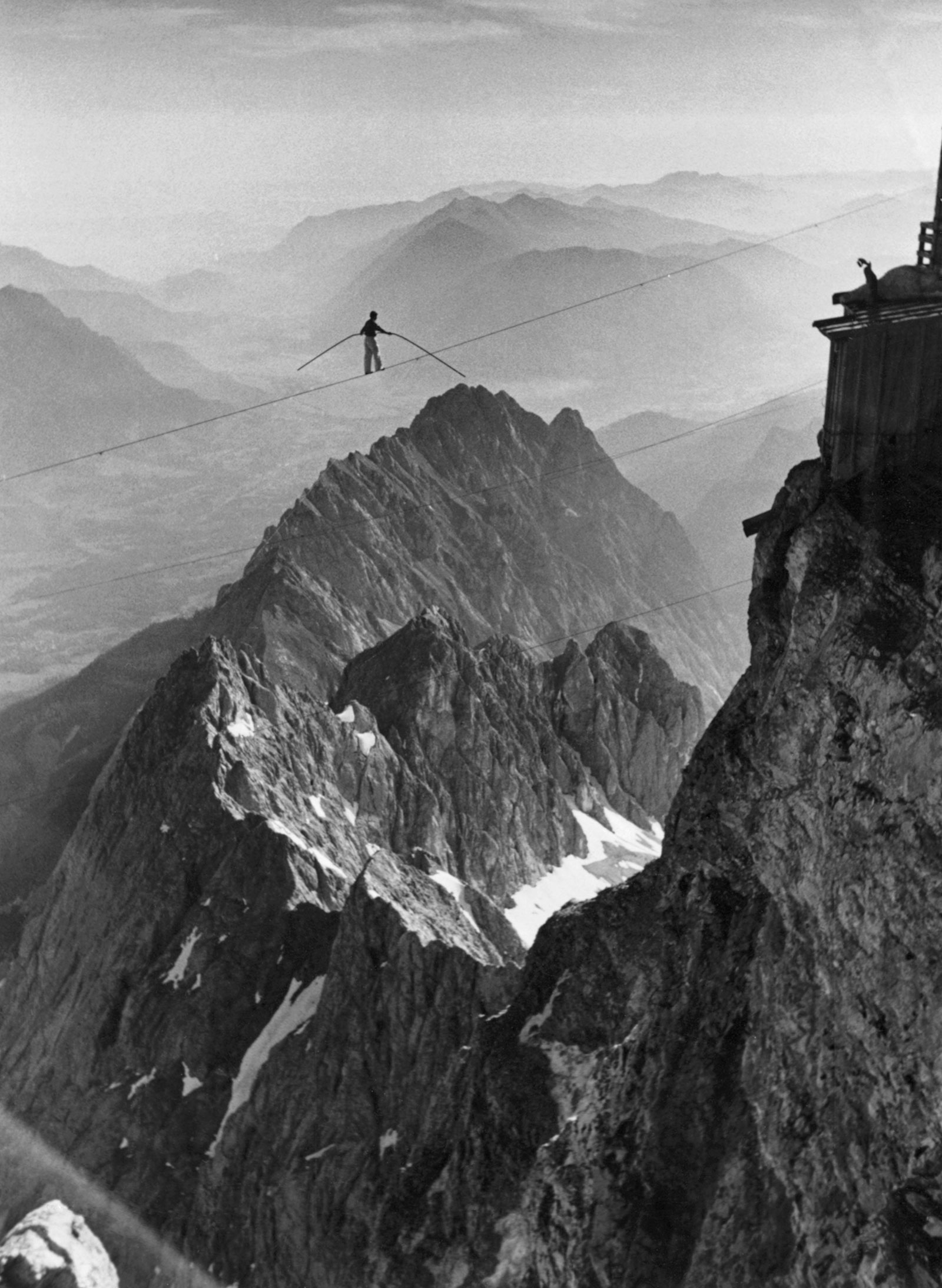

Meantime, Zimmer, driven out of Breslau, had regrouped in Dresden and planned to exit not with a whimper but with a bang: a tightrope walk over the Alps. “The nerviest high-wire act of any century,” Life touted on 23 August 1948. A hundred and thirty meters of wire at an elevation of over twenty-nine hundred meters, an aerial border crossing between the Austrian summit of the Zugspitze and a cable car dispatch tower in Germany, wide international publicity, and a share of proceeds going to German children in need and to worker welfare—all this would repatriate the heights where they belonged, in the mountains. Easier said than done. For days, local climbers and technicians crawled about the slopes to fasten the cables that secured the wires, only to discover they didn’t have enough length. Eventually American and Bavarian contributions fixed the snag, but then on the morning of the stunt the wind picked up. The barefoot star, Sigwart Bach, dangled among the peaks “like a cross pendant,” Der Spiegel wrote.[30]

At nineteen, Bach was a wise choice for many reasons. One was his long-time sweetheart Gisela Lenort, a fellow Breslauer and an acrobat poised on the wire’s German end. Amid the stunt, she rushed toward Bach, kneeling in front of him. Two lovers rejoined on a “death walk” over Hell Valley: there could not have been a more over-the-top Romantic scene. But to everyone’s surprise, kitsch was not on the program. In a move that would have seemed disappointingly unsentimental under different circumstances, Bach stepped over his girlfriend and hurried into Zimmer’s teary (and, presumably, fatherly) embrace. This celebration of expellee talent—top talent, literally—may have been too subtle for the audience or the press, but it is difficult to ignore in retrospect.

In 1949, Bach returned for an even more chilling stunt with two colleagues, Jupp Klein and Rudi Bohme.[31] Zimmer’s troupe had recently lost a member while performing in Hamburg, but now an American entrepreneur was offering his patronage, and a Life correspondent readied for a photo-feature showcasing the double death walk, the motorcycle handlebar stand, and the hanging by the feet and, yes, the teeth. Gisela had stayed at home, changing diapers, Der Spiegel gibed: the couple was now married.

A year earlier, the news of their engagement on a highwire in Dortmund had stunned writer Erich Kästner. “I find,” he joked, “one has to codify this new custom in law, by permission of military authorities.” All engagements occurring on the ground should be void, he went on. And why stop at engagements? “Wedding nights, honeymoons, baptisms, divorces, deliveries, export provisions, reconstruction plans—onto the wire, onto the wire!”[32] The resurgent idea that Germany’s future balances on a tightrope, he continued, was no coincidence. Look at all the tightropes among the ruins, he exclaimed, among the occupation zones and the German states, with “the new type of person” teetering high above! There you have Nietzsche’s light-footed Superman, Kästner ironized: “From Zarathustra to the Camilla Mayer Show to this new, time-appropriate form of existence—life on the wire.”[33] His biting summary outed the falseness of self-reinvention as much as it acknowledged the fundamental precariousness of life in war and in peace.

- Max Frisch, Sketchbook 1946–1949, trans. Geoffrey Skelton (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977), p. 178.

- Annie Dyer Nunn, “Daredevils Walk the ‘Big Top’ Wires,” Popular Mechanics, vol. 100, no. 1 (July 1953), p. 72.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, trans. Thomas Common (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1911), p. 16.

- Max Frisch, Sketchbook, p. 178.

- Rainer Rudolph, “Bewegende Geschichte hinter dem Bild einer Drahtseilartistin in Köln,” Kölner Stadt Anzeiger, 11 December 2016. Available at ksta.de/koeln/historisches-foto-bewegende-geschichte-hinter-dem-bild-einer-drahtseilartistin-in-koeln-25252982?cb=1607445439123.

- Rainer Rudolph, “Wer war die Seiltänzerin vom Heumarkt?,” Kölner Stadt Anzeiger, 28 January 2017. Available at ksta.de/koeln/historisches-koeln-wer-war-die-seiltaenzerin-vom-heumarkt–25635212?cb=1607445437363.

- Tait Keller, Apostles of the Alps: Mountaineering and Nation Building in Germany and Austria, 1860–1939 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), p. 184.

- Max Frisch, Sketchbook, p. 176.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra, p. 9.

- Alfred Andersch, “Das junge Europa formt sein Gesicht,” Der Ruf, 15 August 1946; quoted in Dieter Felbick, Schlagwörter der Nachkriegszeit, 1945–1949 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2003), p. 519.

- See Peter Payer, “Stadt unter Schock: Der Todessturz des Seiltänzers Josef Eisemann im Sommer 1949,” Wiener Geschichtsblätter, vol. 67, no. 2 (2012). Available at stadt-forschung.at/downloads/Stadt%20unter%20Schock.pdf.

- Patrick Anthony, “Mines, Mountains, and the Making of a Vertical Consciousness in Germany ca. 1800,” Centaurus, vol. 62, no. 4 (November 2020), pp. 619–620. Available at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1600-0498.12337.

- Theodore Ziolkowski, Romanticism and Its Institutions (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), p. 27.

- Max Frisch, Sketchbook, p. 178.

- Ludwig Binswanger, “Extravagance (Verstiegenheit),” in Binswanger, Being-in-the-World: Selected Papers of Ludwig Binswanger, trans. Jacob Needleman (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1967), pp. 342–350.

- W. G. Sebald, On the Natural History of Destruction, trans. Anthea Bell (New York: Modern Library, 2003), p. 41.

- Hannah Arendt, “The Aftermath of Nazi Rule: Report from Germany,” Commentary, vol. 10, no. 4 (October 1950). Available at commentarymagazine.com/articles/hannah-arendt/the-aftermath-of-nazi-rulereport-from-germany.

- Max Frisch, Sketchbook, p. 177.

- Ibid., 179.

- Ibid., 176.

- Hans Bernhard Reichow, Organische Stadtbaukunst: Von der Großstadt zur Stadtlandschaft (Braunschweig, Germany: Westermann, 1948), p. 182.

- Caroline Schaumann, “The Return of the Bergfilm: Nordwand (2008) and Nanga Parbat (2010),” The German Quarterly, vol. 87, no. 4 (Fall 2014), p. 419.

- See Jaimey Fisher, Disciplining Germany: Youth, Reeducation, and Reconstruction after the Second World War (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2007), pp. 192–193.

- For more on Camilio Mayer, see circopedia.org/Camillio_Mayer.

- For more on Camilla Mayer, see circopedia.org/Ruth_Barwinske. This page omits the existence of the original Camilla; Max Frisch quotes a show announcer who declares that the late Charlotte Witte was the founder of the troupe, a story that by 1948 may have become part of its founding myth. See Frisch, Sketchbook, p. 178.

- See, for instance, “Zweimal Camilla,” Der Spiegel, no. 44 (30 October 1948). Available at spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-44419656.html

- See “Ein Mann geht durch die Luft,” Der Spiegel, no. 25 (19 June 1948). Available at spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-44417240.html.

- See “Mann ohne Fehltritt,” Der Spiegel, no. 14 (3 April 1948). Available at spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-44415981.html

- Annie Dyer Nunn, “Daredevils Walk the ‘Big Top’ Wires,” p. 77.

- “Ein Mann geht durch die Luft.” Sigwart is also rendered as Siegward in some reports.

- See “Mit Intimitäten fing es an,” Der Spiegel, no. 39 (22 September 1949). Available at spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-44438318.html. In some reports, Bohme is spelled Böhm.

- Erich Kästner, “Verlobung auf dem Seil,” in Kästner, Verlobung auf dem Seil: Vom Heiraten und sonstigen Schwierigkeiten, ed. Sylvia List (Zurich: Atrium Verlag, 2017), p. 123. My translation.

- Ibid., p. 124.

Yuliya Komska teaches in the German Studies Department at Dartmouth College. She is the author of The Icon Curtain: The Cold War’s Quiet Border (The University of Chicago Press, 2015) and the co-author of Linguistic Disobedience: Restoring Power to Civic Language (Palgrave, 2018). She is currently finishing a biography of Margret and H. A. Rey, who created the fictional primate Curious George.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.