The Enemy as Sociologist

American exceptionalism as diagnosed by the Nazi propaganda magazine Signal

Sara Krolewski

Long before Donald Trump was calling for America to be made “great” again, the Nazi propaganda magazine Signal wrote of an American people “which was once great.”[1] “American reality—gone with the wind,” proclaimed the subheading of a 1943 article on the industrialization of agriculture in the United States. Writing in usually flawless English, Signal’s editors criticized what they saw as a degenerated, yet still alarmingly strong, United States: a land of abundance and possibility, now riven by greed, vice, and conformity, and spurred on by ceaseless imperialism. “Today the Americans are busy introducing their economic system of careless and ruthless exploitation to other parts of earth,” the editors wrote. “They pretend they are fighting for democratic liberty, but in actual fact they are systematically extending their power.”[2] This was a United States whose influence only a united Europe—under the aegis of Nazi Germany—could restrain. In the pages of Signal, a magazine designed to vouch for the force and credibility of Nazi Germany, the United States was an enemy who had once been something of a model. But it was a nation that could not be made great again. Instead, it had to be resisted.

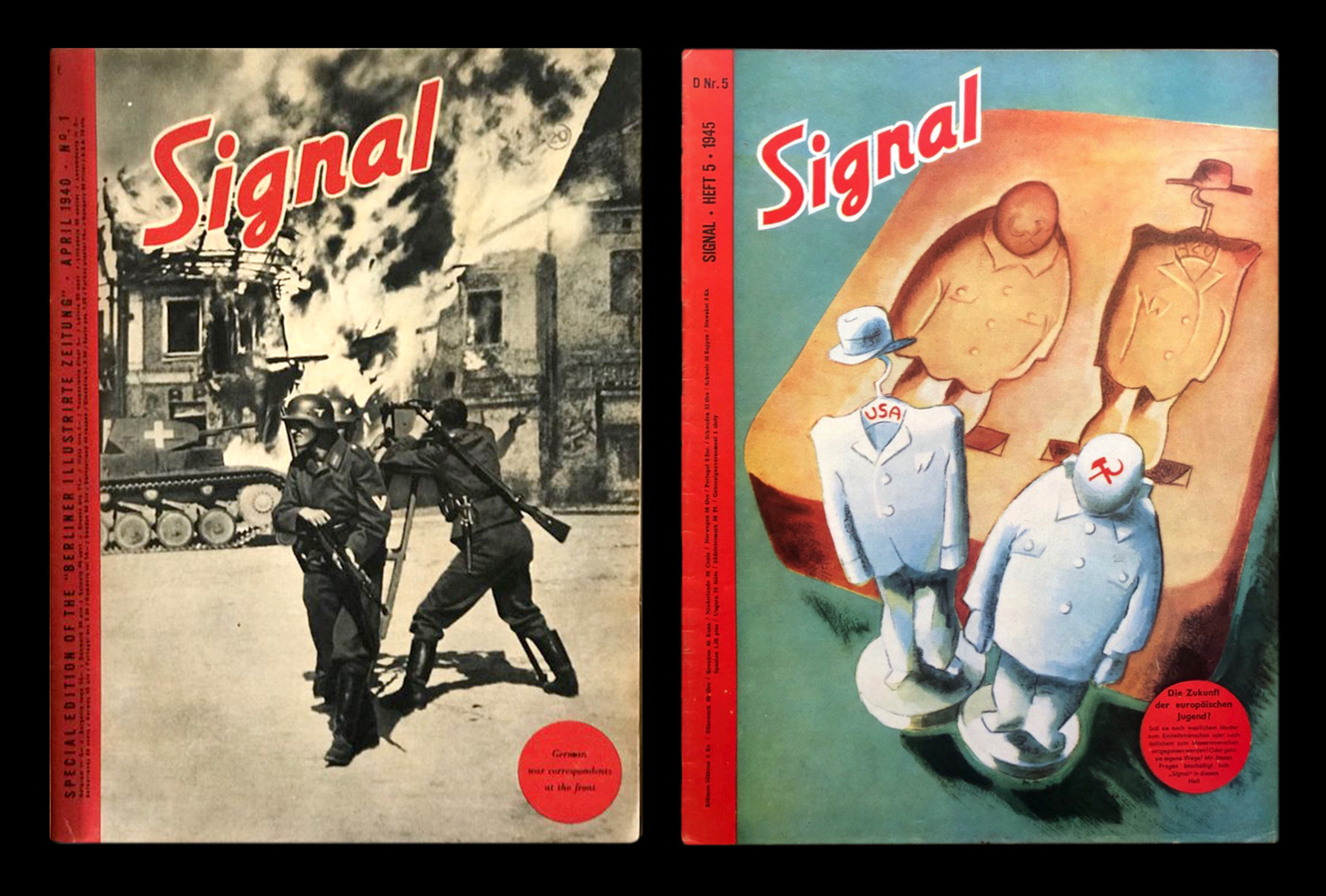

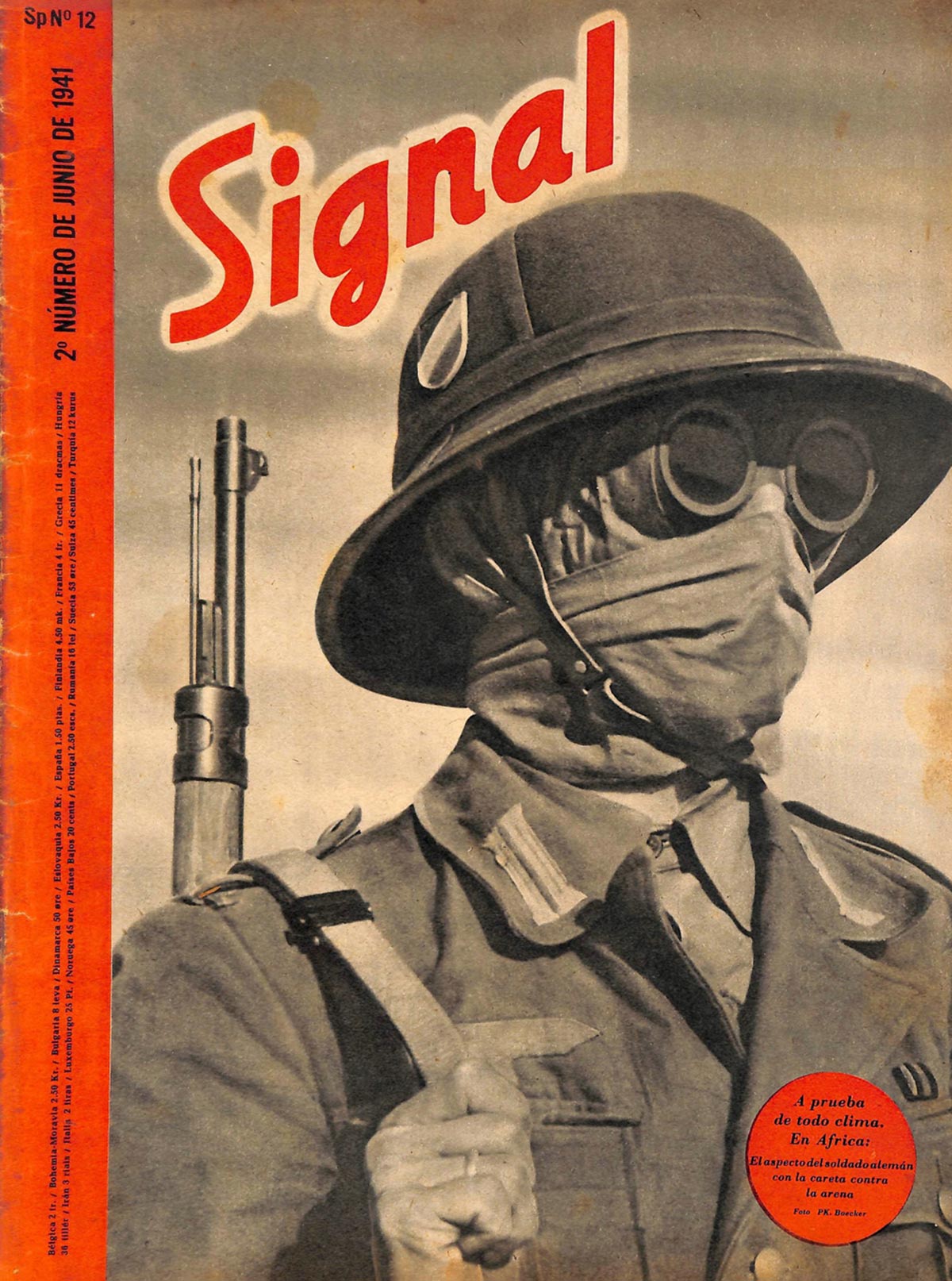

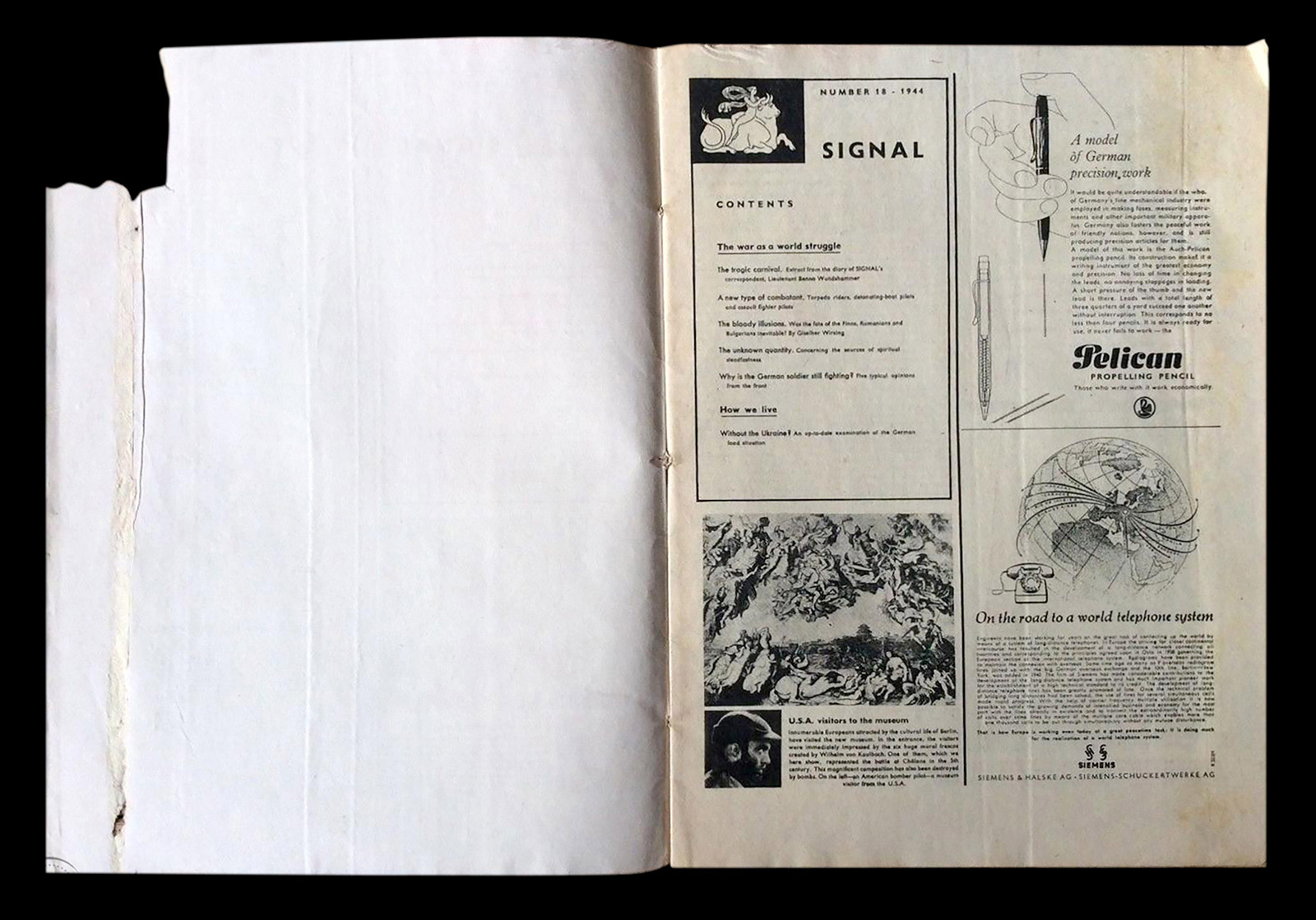

In 1943, Signal—a glossy magazine produced by the Wehrmacht, the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany, and best known for its rare and striking wartime photos—was “the most widely selling magazine in occupied Europe,” reaching a readership of over 2.5 million.[3] Starting in 1940, it was published in languages other than German, including Italian, French, English, and Dutch. By 1942, there were twenty-two foreign editions circulated in total, ranging from Finnish and Serbian to Turkish and Arabic.[4] The magazine was distributed globally, though aimed largely at a European audience: readers in nations Germany had conquered or hoped to conquer, and those in a handful of neutral countries, including Sweden. Within Germany, the magazine circulated only among the military. The English-language edition was imported into the United States (until the end of 1941, when the US entered the war), the neutral Republic of Ireland, and the German-occupied Channel Islands of Guernsey and Jersey.[5]

Signal was an insidious tool of Nazi ideology, meant to counteract an image of fanaticism and indiscriminate violence: by late autumn 1943, as many Jews as Signal readers had been murdered in Poland’s extermination camps.[6] A rosier, apparently benign Germany could be found in Signal’s editorials and photo-essays. German youth, film stars, and soldiers posed for full-page photo spreads, symbols of a robust, nurturing empire. In a 1943 essay entitled “Nazalia: The Girl from the Ukraine,” Signal’s editors profiled a young Ukrainian woman who was rescued by a German soldier after her village was destroyed. Germany, Signal suggested, had civilized the Ukrainians, the “unspoilt children of nature,” and obtained better lives for them.[7]

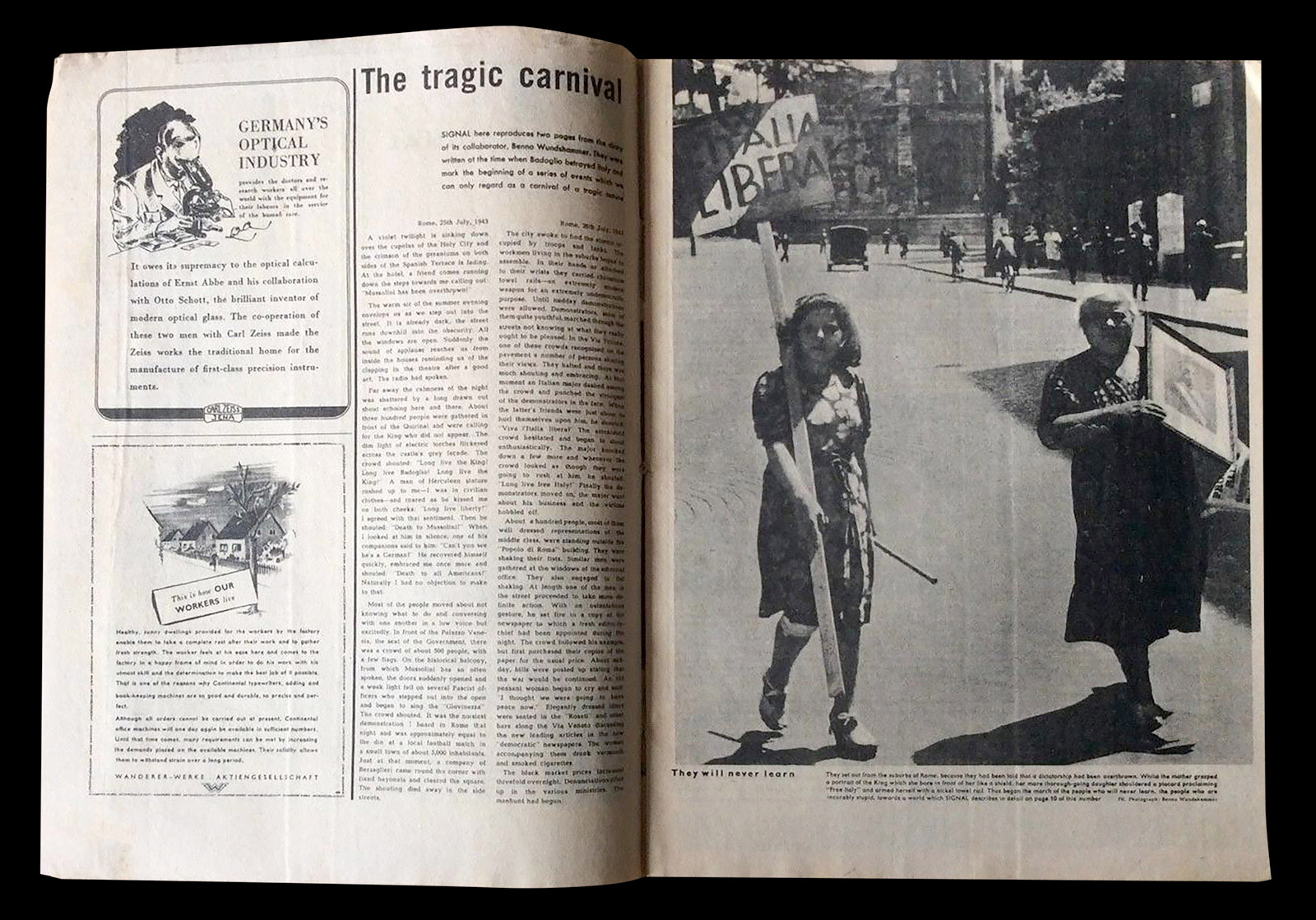

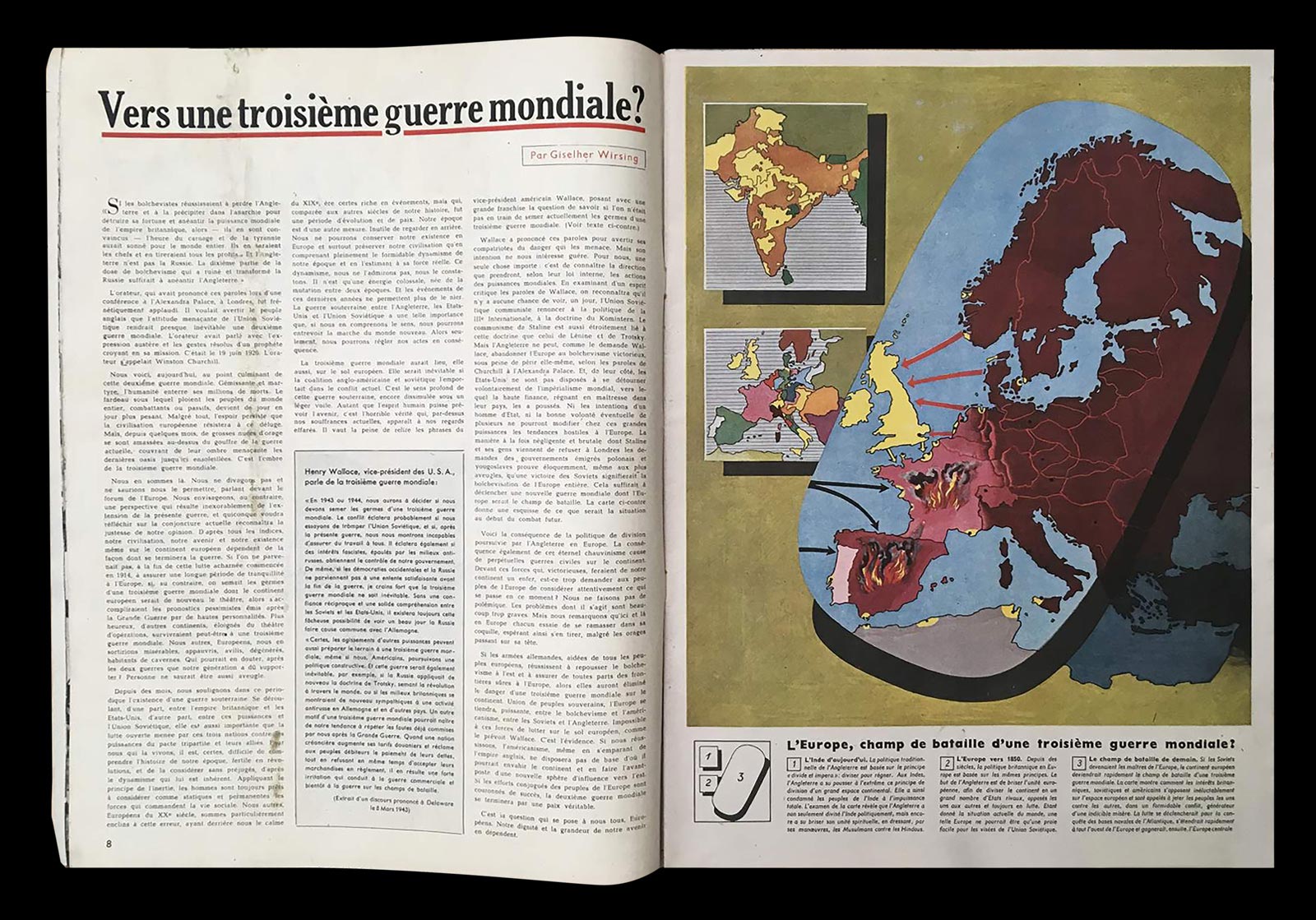

In reality, after the defeat at Stalingrad in early 1943, the Germans were on the brink of losing the war. The tenor of Nazi propaganda changed accordingly, replacing bombastic descriptions of military triumphs with a gentler form of persuasion, and a “more sober, realistic tone of rationalized hope.”[8] Signal’s own argument to readers was simple and enticing. By joining forces with Germany—or choosing not to resist Nazi occupation—their countries could avoid US and Soviet intervention, and the destructive effects of capitalism and socialism. Neither economic system, Signal argued, would improve life in Europe. In short, polemical essays, Signal’s editors sharply condemned both nations, with occasional jabs at Great Britain and France.

But in the English-language edition, they paid particular attention to the United States, demonstrating a surprisingly thorough understanding of the current events of their opponent to the west. By 1943, the issues in English were only available to readers in Ireland and the Channel Islands, who would have been more familiar with the culture and politics of the United States than of the Soviet Union. The idea, then, was to convince these readers of the United States’ weaknesses and mounting failures.

By contrast, the American propaganda magazine Victory—produced by the Office of War Information in response to Signal and also disseminated in Europe, though with less than half of the former’s circulation—only contained content about the United States, mainly “general articles on America’s war effort and ‘evergreen’ pieces focusing on showing ‘how America lives.’”[9] Signal’s focus on the United States makes the magazine all the more striking as a work of propaganda: one that took pains to depict its adversary with depth and clarity, and occasionally, a note of mild approval.

In the 1943 English-language edition of Signal, a series of articles under the heading “Americana” explored and analyzed fissures in American society. Many of these reproduced excerpts from US magazines and newspapers—snippets offered as proof for Signal’s anti-US claims, and to bolster the magazine’s credibility. One article, “Concerning the ‘Victory Girl’ and What ‘Collier’s Magazine’ Has to Say about Her,’” drew on a March 1943 Collier’s article describing a trend among young women, dubbed “Victory Girls,” of pursuing sexual relationships with soldiers and sailors. “After reading a large number of American newspapers and periodicals published in 1943 … even the most impartial observer must obtain a nothing less than shocking impression of the moral degradation of a certain part of the people of the United States,” wrote Signal’s editors.[10] “We do not wish to make vague assertions and will consequently quote what has been said in America itself,” they added, before directly quoting from Collier’s. In addition to “Victory Girls,” the article also detailed instances of juvenile delinquency and crime in Los Angeles, Detroit, and New York City, which Signal pointed to as evidence of America’s “internal decay.”[11]

These same themes were echoed in “Americana: Zoot Suiters—Jitterbug,” which cited an article from Time magazine describing the 1943 Los Angeles Zoot-Suit Riots, in which white servicemen and residents attacked Black and Mexican-American youths attired in “zoot suits,” a type of suit fashionable with non-white, working-class Angelenos. “America has here to do with one of the particularly outstanding characteristics of the complete break-up of discipline and morals in her youth,” Signal’s editors remarked (in a poor English translation, perhaps a result of waning resources for the English-language edition). Yet they were also critical of the racial tensions at play—rebuking the “sailors and whites” who “flogged” the “zoot suiters.”[12] “They want to be American,” the editors wrote of the victims, but “the rest of the Americans refuse to recognize them in any way. They are neglected and abandoned like wreckage and drift-wood on the seashore.”[13]

Another “Americana” essay, “Between Favour and Hatred,” offered explanations for the “colour riots” that had taken place in various cities in the summer of 1943: “indescribable” living conditions for Black migrants in the North; white workers’ fear of losing their jobs to lower-paid Black workers; Washington politicians’ hollow, inefficacious rhetoric of social progress.[14] The editors offered this oddly prescient diagnosis: “The unsolved colour problem is gnawing deeper and deeper like a slow venom into the unstable, social structure of the U.S.A. The color riots this summer are in all probability only the forerunners of even more serious disturbances.”[15] At a time in which US publications tended to malign minorities—an editorial in the Tucson Daily Citizen from 1943 noted that “all wearers of the [zoot suit] are suspect”—Signal reflected instead on the oppression they faced, portraying racial hatred and strife as symptoms of America’s own deterioration.[16]

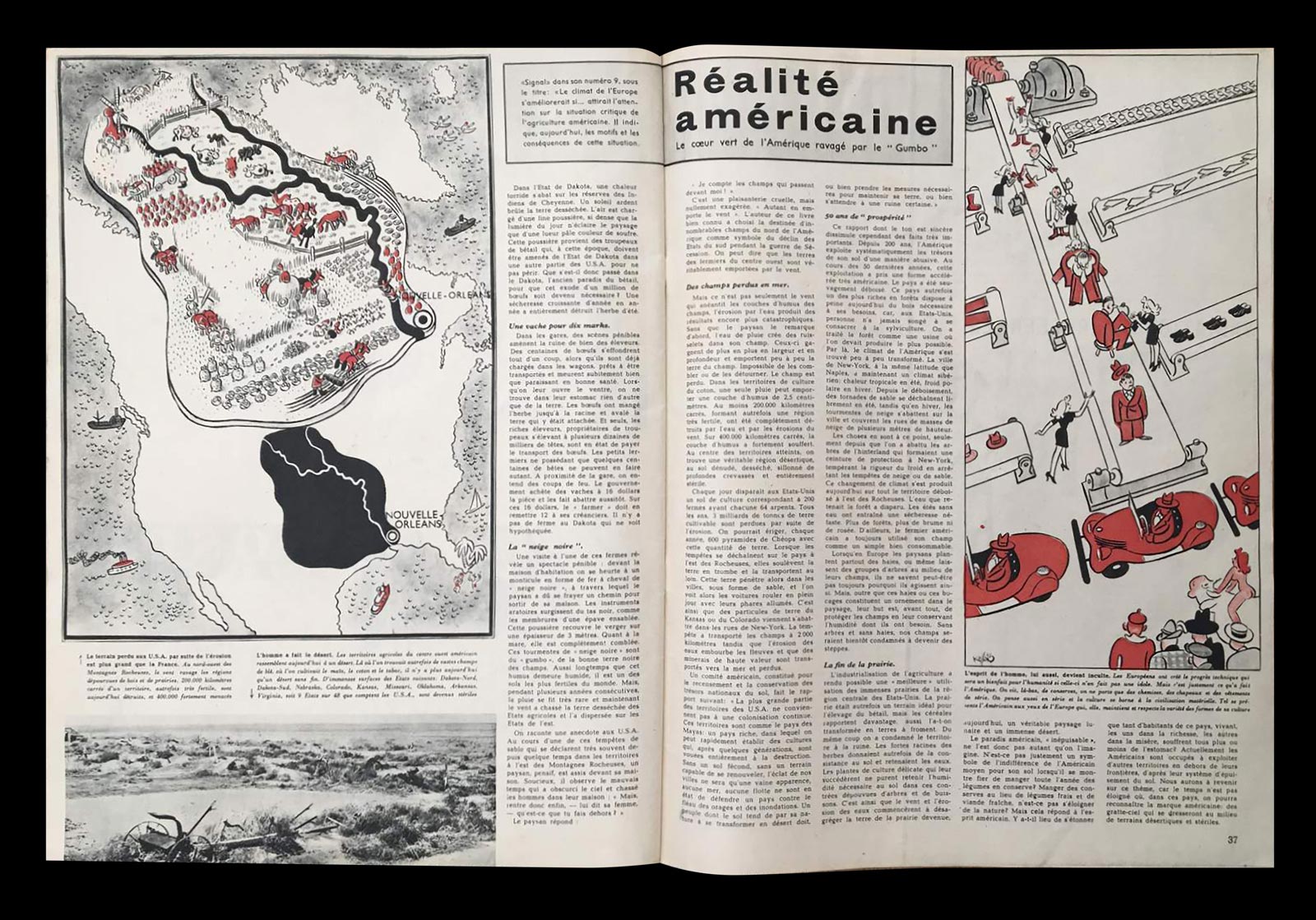

Unusually for German propaganda, Signal’s anti-American appeals were factual and free from harsh invective. In striving for persuasion and an intellectual, highbrow tone, Signal was careful to avoid the aggressive language of anti-Semitism and racism found in the newspapers Der Angriff (“The Attack”), founded by Joseph Goebbels in 1927, and Das Schwarze Korps (“The Black Corps”), the official newspaper of the SS. Nor did Signal resort to caricature, as US propaganda often did—for example, depicting Japanese soldiers as exaggerated, grotesque figures.[17] Instead, “Americana” essays were detailed examinations of social and cultural dilemmas, often focused on the weaknesses of American capitalism. In an “Americana” essay entitled “The Green Heart of America,” Signal’s editors described the deforestation of the country’s hinterland and the industrialized “exploitation of the broad prairie land in the heart of America,” processes that had left vast swaths of land unusable and affected weather patterns.[18] Signal viewed farmers in the Midwest, like factory owners in cities, as individuals blindly motivated by profit, rather than by duty or care for their country. “The American farmer has always looked upon his land as something to be exploited,” they noted: these farmers had contributed “to a remarkable modification in the American climate,” while urban businessmen incited labor conflicts.[19]

A critique of the failure of the United States to properly manage its forests and agricultural lands. The unsigned article argues that the lack of stewardship is a function of the country’s rampant materialism and fetishization of technology.

From the French-language edition of the second of

the two issues published in May 1943.

In Signal’s view, capitalism had even stripped the United States of any authentic culture. In a cartoon accompanying “The Green Heart of America,” workers are assembled in identical outfits on a conveyor belt, then placed into matching vehicles. The image’s caption explains that in the United States, “people now live on tinned food, wear standardized shirts, standardized hats, and standardized suits. Thinking has been standardized too, and in American civilization there is no place for culture.”[20] Without the clear nationalist rhetoric of other Nazi publications, Signal’s critiques of American capitalism scan as accurate, even percipient—prefiguring the work of later US writers like David Riesman and C. Wright Mills, who analyzed the effects of capitalism on an increasingly uniform, alienated American middle class.

For all of the anti-American opprobrium of the “Americana” series, a strange ambivalence underscores much of Signal’s writing about and attitudes toward the country. For one, though Signal lamented the state of US culture, the magazine looked to that same culture for inspiration, consciously modeling itself on the American periodical Life. Signal also included the input of Nazi propagandists Major Fritz Solm and Giselher Wirsing, both of whom took particular interest in US society and culture. Signal was the brainchild of Solm, who studied at Columbia University and worked at the New York advertising firm J. Walter Thompson in the 1920s. After returning to Germany in the 1930s, he became involved with the Division for Defense Propaganda, a branch of the Wehrmacht. Drawing on his experiences as a marketer in the United States, Solm, together with economist Heinrich Hunke, approached the leadership of the Wehrmacht in the autumn of 1939 to propose a propaganda magazine in the style of Life: a general-interest publication for the European middle-class reader, with colorful photo spreads and articles on current events.[21] Solm hoped to replicate Life’s success, appealing to the same demographic in Europe. Life itself would eventually describe Signal as part of the “great, intricate and effective propaganda machines” of “Berlin, Rome and Tokyo”—deeming the Axis powers’ publications and ephemera more “slashing” than American propaganda like Victory, which was also modeled after Life.[22]

Wirsing, a journalist and SS captain who became Signal’s chief editor in 1943—overseeing the production of the “Americana” series, and contributing to the content of many of the articles—was fluent in English and had frequently traveled to the United States to report for German magazines. In spring 1938, on a trip financed by the weekly magazine Münchner Illustrierte, Wirsing had met with Henry Luce, the owner of Life, and the magazine’s editorial staff; later, he had had a private conference with President Roosevelt, and meetings with several US senators. Though Wirsing primarily used the trip to advocate for Nazi Germany—“expound[ing] the beneficial and rational influence of Nazi Germany on Europe” to the politicians he met—and would later write a vitriolic book, Der maßlose Kontinent (The excessive continent), on the United States under Roosevelt, his curiosity about the country seems to have been acute.[23] His five-month tour of the United States included stops in New York City and Washington, DC, but also the South (including Atlanta, where he met Margaret Mitchell, the author of Gone with the Wind, a title alluded to in the subheading of one “Americana” essay), the West (where he toured film studios in Hollywood), the Midwest (in Detroit, he visited Ford and General Motors), and New England (where he spent time at Harvard University). Many of these stops likely provided fodder for the “Americana” essays. But the breadth of Wirsing’s trip also suggests his familiarity, and even fascination, with American geography, industry, and art. Clearly, both Wirsing and Solm found something to admire in the United States, even as they helped shape Signal into an anti-American magazine.

This same faint sense of admiration runs beneath many of the “Americana” pieces, surfacing in subtle ways. In “The Green Heart of America,” Signal’s editors described a nation whose resources made it worthy of respect, though its prosperity was unlikely to last: a “rich country in which a culture can spring up in a very short time only to disappear in the course of a few generations.”[24] The American’s carelessness and avarice, his “lack of appreciation of his own soil,” were bound to transform this abundant, fast-growing country into a barren, lifeless one.[25] Even US cities, in which Signal saw moral decay, corruption, and destitution, had been venerable at one point: “Without a fruitful soil and without forest land which is perpetually renewed the splendour of the cities will become a ghostly shadow.”[26]

In “Concerning the ‘Victory Girl,’” Signal identified a select group of Americans still upholding moral standards in the face of national decline: “Even today there is another America for which morals and decency still exist—but it is condemned to silence and patience.”[27] What was this “other America” that might redeem its other, fallen half? Here, Signal remained oblique, but its editors were more forthright in their admiration for the pace and extent of industrialization in the United States, an outlook that was widely shared not just throughout Nazi Germany but in continental Europe as a whole. As Klaus P. Fischer writes in Hitler and America, as late as 1942 Hitler was praising the industrial and technological achievements of the United States, which had provided its citizens with wealth and autonomy, even as he denounced the country as a materialist, “degenerate and corrupt state.”[28] Such admiration had a long history and had only intensified in the wake of World War I, as the United States saw widespread industrialization and the growth of its nouveaux riches, while many parts of Europe lay devastated, economically and otherwise. At the same time, the means by which industrialized success had been achieved in the United States had led some Europeans to regard it as a nation of “spiritual emptiness”—materially wealthy, but lacking tradition or forms of community, and worshipping consumption above all else.[29] Signal played into these common assumptions and attitudes, while standing in for the ideological apparatus of the Nazi state.

We tend to think of propaganda as distortion, but Signal cannot neatly be classified as such. Its editors combined careful reporting—supported by Wirsing’s research and excerpts from US magazines and newspapers—with blustery calls for European unification; the “Americana” series portrayed America with more nuance and ambivalence than might be expected, striving for thoroughness instead of straightforward denunciation. As a stealthy instrument of Nazism, Signal omitted truths about Germany’s own crumbling war efforts. But its analyses of problems in the United States have a ring of accuracy to them—in many cases, more so than even US publications—reflecting its architects’ keen interest in the country.

Reading Signal today, I had the strange, uncomfortable feeling that I was agreeing, at least partially, with analyses promoted by the United States’ most notorious enemy. Several of Signal’s “Americana” critiques are still pertinent, echoed in various ways by contemporary critics. Have we yet arrived at any definite, lasting solutions to racial discrimination, climate change, and the deleterious consequences of capitalism? Have we at all tempered our “system of careless and ruthless exploitation,” or merely continued it? An overarching narrative of American exceptionalism has often impeded necessary progress. It can be (and has repeatedly been) said that Americans are blind to their own long record of faults and failures. If this extreme myopia does in fact define us as a people, an artifact such as Signal asks us to consider: What if our enemies know us better than we know ourselves?

- [n.a.], “Americana: Concerning the ‘Victory Girl’ and What ‘Collier’s Magazine’ Has to Say about Her,” Signal, no. 16/2 (August 1943), p. 38. At its peak, Signal was publishing two issues per month; the issue number notations throughout these notes indicate whether the issue was the first or second in a given month.

- [n.a.], “The Green Heart of America: American Reality—Gone with the Wind,” Signal, no. 10/2 (May 1943), n.p. Some issues of Signal were unpaginated.

- S. L. Mayer, Signal, Years of Retreat, 1943–1944: Hitler’s Wartime Picture Magazine (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1979), n.p.

- S. L. Mayer, Signal, Hitler’s Wartime Picture Magazine (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1976), n.p. The tally of of foreign editions is derived from the research of Alexander Zöller et al. See signalmagazine.com/files/editions.gif.

- As Jordan Henry notes in “‘We Europeans’: Signal Magazine and Political Collaboration in German-Occupied Europe, 1940–1945,” “as late as 1943, content from the magazine was still being reproduced in American newspapers, including the Cleveland Plain Dealer.” While some Signal-produced reports appeared in US newspapers after 1941, full versions of the English-language edition—in which the “Americana” series would have appeared—were not available in the United States after 1941. See Jordan Henry, “‘We Europeans’” (undergraduate thesis, The Ohio State University, 2017), p. 15. Available at kb.osu.edu/bitstream/handle/1811/80695/JordanHenryThesis.pdf.

- Nicholas O’Shaughnessy, Selling Hitler: Propaganda and the Nazi Brand (London: C. Hurst & Co., 2016), p. 77.

- Quoted in S. L. Mayer, Signal, Years of Retreat, n.p.

- Nicholas O’Shaughnessy, Selling Hitler, pp. 83–84.

- Marja Roholl, “Preparing for Victory: The U.S. Office of War Information Overseas Branch’s Illustrated Magazines in the Netherlands and the Foundations for the American Century, 1944–1945,” European Journal of American Studies, vol. 7, no. 2 (March 2012), p. 7. Available at journals.openedition.org/ejas/9629#tocto1n4.

- [n.a.], “Americana: Concerning the ‘Victory Girl,’” p. 38.

- Ibid.

- [n.a.], “Americana: Zoot Suiters—Jitterbug,” Signal, no. 12/2 (June 1943), n.p.

- Ibid.

- [n.a.], “Americana: Between Favour and Hatred,” Signal, no. 19/1 (October 1943), n.p.

- Ibid.

- [n.a.], “The Zoot Suit,” Tucson Daily Citizen, 8 April 1943.

- See, for example, illustrator Harold Von Schmidt’s 1043 advertisement for Chrysler Corporation. Its text begins: “It wasn’t just dark … it was black as Tojo’s heart!” Available at archives.library.wcsu.edu/omeka/items/show/4666.

- [n.a.], “The Green Heart of America,” n.p.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Jordan Henry, “‘We Europeans,’” p. 12.

- [n.a.], “U.S. Propaganda,” Life, vol. 14, no. 12 (22 March 1943), p. 12. Available at books.google.com/books?id=KVEEAAAAMBAJ&dq=.

- An account of Wirsing’s trip is given in a report prepared by the US Army International Center Interrogation Section in 1946, when Wirsing was being held as a prisoner of war. See www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/WIRSING%2C%20GISELHER_0016.pdf.

- [n.a.], “The Green Heart of America,” n.p.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- [n.a.], “Americana: Concerning the ‘Victory Girl,’” p. 38.

- Klaus P. Fischer, Hitler and America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), p. 10.

- Ibid.

Correction

4 May 2021: An earlier description of the cartoon accompanying “The Green Heart of America” misidentified the various Europeans watching the American conveyor belt. We have deleted the erroneous portion of the description. Our thanks to Daniel Dittmar.

Sara Krolewski is the Stenbeck Fellow in Cultural Reporting and Criticism at NYU’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute. A former editorial assistant at Cabinet, she is a graduate of Princeton University and the University of Edinburgh, where she was a Witherspoon Scholar.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.