Two Lives, Simultaneous and Perfect

Éric Rohmer and the erotics of chastity

Becca Rothfeld

By all accounts, Maurice Schérer led an oppressively virtuous life. He never cheated on his wife. He was sober, refusing both drugs and alcohol, and he attended Mass each Sunday. Though he could have afforded a car, he never bought one, and he considered even occasional taxi trips an undue extravagance. In his old age, when he was suffering from painful scoliosis, he continued taking two buses to work in the Montparnasse neighborhood of Paris each morning, then the same two buses back home each night. He cherished quiet enjoyments: classical music, visits to museums, nights at home with his family. He was born in 1920 and died in 2010, but he never owned a telephone.

What does this self-effacing ascetic have to do with Éric Rohmer, the elusive yet glamorous filmmaker who has been called “the father of French New Wave”? Perhaps it is only incidental that they were, in fact, the same person, for the two of them led remarkably discrete lives. Schérer was a teacher of high school Greek and Latin when he started publishing film criticism, first in magazines run by others, then in a short-lived journal he founded himself, and finally as the editor of the legendary Cahiers du Cinéma. Soon after he began writing, he adopted the pseudonym “Éric Rohmer,” a nod to mystery writer Sax Rohmer and director Erich von Stroheim, to prevent his touchy mother from discovering his true vocation. Yet even when the old woman died, oblivious, in 1970, he remained fanatical about keeping his private life sealed apart from his art. His wife and two sons sometimes accompanied him on filming trips, but they were never permitted on set; they did not meet his colleagues until he was lying on his deathbed.

If Schérer and Rohmer intersected at all, they must have done so on screen. And Rohmer’s films are indeed marked by Schérer’s trademark abstemiousness. “The essence of Rohmerism is restraint,” Richard Brody once declared in The New Yorker.[1] The director’s style is elaborately unadorned, in some ways quasi-documentary: Rohmer eschewed artificial soundtracks in favor of natural noises, and many of his stars were unmannered amateurs. He sometimes named his characters after their actors, with whom he often collaborated on screenplays, making tapes of long conversations that he subsequently incorporated into his movies. Just as he preferred the organic rhythms of casual speech to the stilted dialogues of the writing room, he preferred shooting on location to constructing sets. His films are saturated with the natural environment—the chirping of birds, the rush of the wind, the plashing of waves lapping at the dock. Rohmer once planted a rose and waited a month for it to bloom so that an actor could pluck it.

His plots, insofar as there are any, are as unassuming as his settings. In many of his movies, nothing happens, except that people talk and talk. Famously, Gene Hackman’s character in the 1975 neo-noir Night Moves quips, “I saw a Rohmer film once. It was kind of like watching paint dry.” But Rohmer’s work is not boring so much as it is lulling. Daily tasks—the picking of cherries, the cooking of dinner, the steeping of tea—are performed so deliberately that they acquire a kind of sumptuousness. Rohmer, who considered himself a realist in the tradition of Jean Renoir, aspired to “make people forget the camera” so that they could see past art and straight to the truth.[2] “Beauty and order are only in the world,” he once told an interviewer. “For how could art, a human product, be the equal of nature, a divine work? At best it is only the revelation, in the universe, of the hand of the creator.”[3] Despite his intentions and his fervent Catholic convictions, his films are beatifically stylized, blond with gentle light. Are they really restrained? Or do they just trade in unfamiliar forms of exaltation?

• • •

Perhaps most straightforwardly restrained of all Rohmer’s works are the quietly voluptuous “Moral Tales,” the six movies that made his career. Filmed between 1962 and 1972, the Tales are all based on stories that Rohmer wrote in his youth, and they all have roughly the same plot. “The temptation and rejection of a false love while waiting for a true one,” is how Brody characterizes their shared preoccupation. As Rohmer himself put it:

I conceived of my moral tales as six symphonic variations. Like a musician, I vary the initial motif, I slow it down or speed it up, stretch it or shrink it, add to it or purify it. Starting with the idea of showing a man attracted to a woman at the very moment when he is about to marry another, I was able to build my situations, my intrigues, my denouements, right down to my characters.[4]

Not all of the male protagonists of the Moral Tales are, in the straightforward sense, “about to marry another.” In Love in the Afternoon (1972), the sixth and most exquisite, the businessman Frédéric is already a husband and father. In the first two works of the series, shorts that were never theatrically released and that did not become widely known until after Rohmer was famous, men pine after women they have yet to even court. And in what Rohmer regarded as the third Tale (though it was filmed fourth), My Night at Maud’s (1969), a pious engineer is intent on marrying a woman he glimpses at Mass each weekend but cannot muster the courage to approach. Still, he feels engaged. “I suddenly knew … Françoise would be my wife,” he announces in a dramatic voiceover near the beginning of the movie, before he has exchanged so much as a single word with the woman.

His impressive yet insane conviction is less like a promise and more like a flinging of faith. The film opens, after all, in a vast stone cathedral, where the engineer, Jean-Louis, is watching Françoise recite prayers along with the priest. Religious faith begins before we are saved, so why shouldn’t marital faith begin before we are engaged, or even acquainted? “The most important thing is the issue of fidelity,” Rohmer once remarked. “Fidelity to a woman, but also to an idea, to a dogma. … Fidelity is one of the major themes of my ‘Moral Tales,’ with betrayal as a counter-subject.”[5]

The betrayal in question is never full-fledged: it is contemplated, not consummated. Still, it is more lushly palpable throughout the Tales than the heroic fidelity that always prevails at the end. In all of the films, temptation shimmers for hours, leaving the brides-to-be to fade into the periphery. In La Collectionneuse (1967), the recipient of the Berlin Film Festival’s prestigious Silver Bear and Rohmer’s first major success, the offending fiancée features for five forgettable minutes—long enough for her to establish that she is about to depart on a work trip. For the rest of the movie, her future husband, Adrien, vacations on the Riviera, where he barely succeeds in resisting a nubile young libertine named Haydée. My Night at Maud’s, which was nominated for two Oscars and the Palme d’Or, is kinder to its resident fiancée, but she, too, is ultimately overshadowed. Jean-Louis glimpses his eventual wife around town, but the movie centers on his searing encounter with the eponymous Maud. Demure Françoise occupies about thirty-five minutes of footage in a movie of nearly two hours. The remainder is devoted to the snowy night Maud and Jean-Louis spend almost-but-not-quite sleeping together.

In Claire’s Knee, the fifth Tale, the fiancée never even makes an appearance, except in the form of an unflattering photograph that one character deems “severe.” Jérôme, named for Saint Jérôme and his canonical temptation, plans to stop at picturesque Lake Annecy before returning home for his wedding. By chance, he runs into Aurora, an old friend who is renting a room from a local family for the summer. At Aurora’s encouragement, Jérôme insinuates himself into the lives of the family’s two teenaged daughters. He is particularly captivated by lithe, delicate Claire—and even more particularly, by her knee. “Every woman has her most vulnerable point,” he tells Aurora during one of their voyeuristic debriefings. “For some, it’s the nape of the neck, the waist, the hands.” Claire’s most vulnerable point is, naturally, the knee, or, as Jérôme puts it, “the magnetic pole of my desire.” In the end, he contrives to stroke the knee in question, thereby excising the last of his illicit lusts. His desire dissipates. The movie ends. We are left to assume that he marries his severe fiancée after it is over.

Claire’s Knee is something of an outlier, and not only because Jérôme indulges rather than renounces his comparatively innocuous appetites. It is also anomalous because his attachment to Claire is so flatly physical. She is graceful but inert: Jérôme discusses her with Aurora, but he only addresses her directly in brief and awkward snatches. The scenery—the roses, the mountains, the intimation of hazy heat—is sultry, but there is no surge of chemistry between Jérôme and the ingenue herself. In contrast, there is something almost spiritual about the aching affinities that arise between the protagonists and the seductresses in all the other Tales.

Strictly speaking, of course, the movies are the picture of propriety, all talk and no sex. But even Rohmer’s most chaste movies brim with touch, much of it more tender and caressing than the standard sexual overtures. In La Collectionneuse, Adrien plays with Haydée’s bracelet, slowly sliding it up her forearm and back down her wrist. In My Night at Maud’s, the two main characters stand in the cold, toying with the collars of each other’s coats and looking effervescently infatuated. These playful gestures are not sexual but erotic: they bespeak not rote lust but a kind of electric affection. The fondness that Rohmer’s quasi-lovers manage to compress into even their smallest motions makes it hard to refrain from rooting for the success—and consummation—of their affairs. They are so euphorically enthralled by one another that we find ourselves against the brigade of severe fiancées and on the side of sensuous Maud and Haydée—and above all, of tempestuous Chloé.

• • •

Love in the Afternoon, sometimes called Chloe in the Afternoon, presents its protagonist not just with a momentary enticement but with a tantalizing glimpse of an entire alternative life. One day, Frédéric finds a woman he used to know (and dislike) sprawling in a chair in his office. He is surprised to see her: she used to date a friend of his, but, in typically chaotic fashion, she abandoned the friend and disappeared for years. While she was careening from one country (and one lover) to another, Frédéric was following the usual, deadening path. By the time Chloé materializes in his office, he has achieved modest success at his firm, secured a small but adequate condo in a peaceful suburb, and married a retiring schoolteacher named Hélène, with whom he has an infant daughter. In other words, he has settled into his bourgeois life the way that people sink, sighing, into overstuffed armchairs. Sometimes, he seems contented; he is always insisting, especially when he is with Chloé, that he is happy.

But he doth protest too much: he has already broken the fourth wall to confess to us, the viewers, that he has frequent pangs of dissatisfaction. “The prospect of quiet happiness stretching indefinitely before me depresses me,” he admits. “I dream of a life comprised only of first loves and lasting loves. … I want the impossible, I know.” He seeks it on the streets of Paris, where he wanders around in despair, admiring women he will never meet. “That’s why I love the city,” he tells us, glancing over at a young couple in a cafe. “People come into view, then vanish. You don’t see them grow old.” Pre-Chloé, Frédéric becomes especially despondent in the afternoons, when he thinks with stinging longing of the “other lives unfold[ing] along paths parallel to mine.” The impossible thing that he wants is everything, every life and every love at once.

He ends up not with all lives but with two: a cozy domestic one with Hélène in the evenings, and a wild one with Chloé in the afternoons. Unlike his mild and responsible wife, his not-quite-mistress is thrillingly unreliable. She quits jobs without a second thought. She convinces Frédéric to meet her in the evening for once, then stands him up and sends him a cheerful card postmarked from Italy. Weeks later, she returns, radiant, in a turquoise suit, and he can’t muster any anger. Where Frédéric nurses subdued and brooding desperation, Chloé runs, weeping, out into the street.

Their relationship is tortured, hopeless, and sweet, full of wonderfully warm gestures: Frédéric gently taps the tip of Chloé’s nose, and she kisses every part of his face except for his mouth, then his mouth, too. All of the near-couples in the Moral Tales are entangled, but Frédéric and Chloé are intricately enmeshed. More than Maud and Jean-Louis, who only spend a charmed twenty-four hours together, and even more than Adrien and Haydée, who flirt perilously for weeks, Frédéric and Chloé seem to love one another with vehemence and virulence. “Is it possible to love two women at once?” Frédéric once dreamily asks her. He even half-proposes, at least half-seriously: “Chloé, would you marry me?” he asks when he glimpses their reflection in a mirror, a portal into the parallel world in which he is leading one of his impossible lives. “You’re married,” she replies. “In real life, sure. But in another life,” he says. “A double life?” she asks him. “Not exactly,” he tells her. “Don’t you ever dream of living two lives at once, simultaneously and perfectly?”

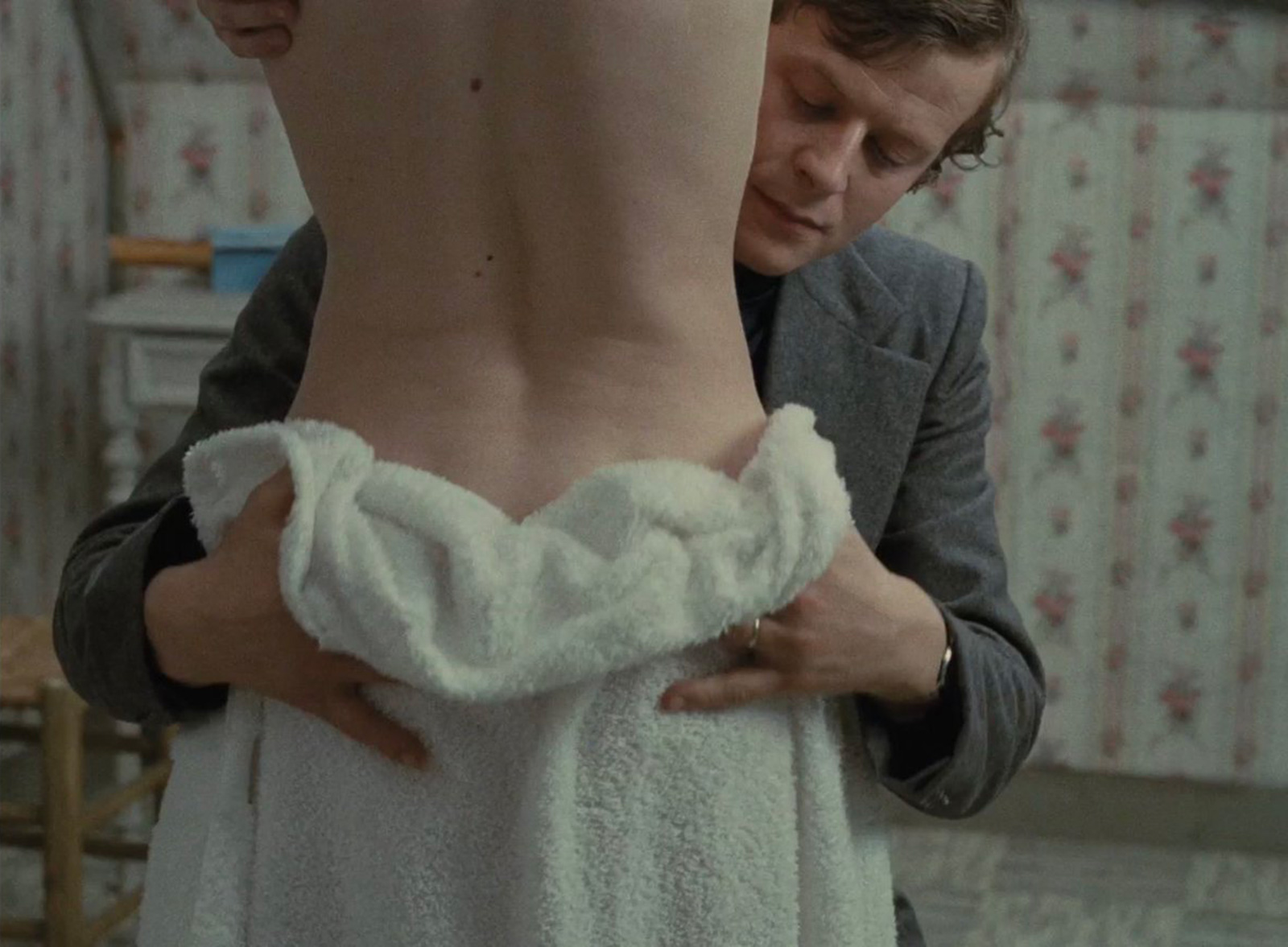

Many times, he comes treacherously close to fully realizing his second life by way of succumbing to Chloé’s advances. When Chloé takes a job in a boutique, she entertains herself by trying on all of the dresses. Frédéric watches her shed one, and before she can don another, he runs his hands along her waist. Near the end of the movie, he hugs her, pressing his hands against her back and inching her shirt up until he is stroking her bare skin with mesmerizing languorousness. And in the painfully wracked penultimate scene, the most beautiful in this and maybe any movie, he dries her off as she emerges from the shower, sliding the towel lower and lower until at last she is gleamingly naked and he is on his knees. The image is so luscious that it is almost unbearable, like snow so bright it blinds. You can neither look nor look away, live neither one life nor the other. But just as Frédéric is about to capitulate, he catches sight of himself in the mirror with his sweater scrunched up around his face. The pose is ridiculous, reminiscent of a goofy stance he once adopted to make his daughter laugh. He is jolted back to drab conscientiousness. He flees to his wife, presumably for good, and they embrace in tears.

It is difficult, at least for me, to celebrate this détente. Earlier in the film, Frédéric assures Chloé that he loves Hélène “because of who she is,” not just because he is married to her. But he never says who she is, and Rohmer never shows us. She appears only occasionally, and when she is on the screen at all, she is usually silent, hunched over her books and papers. If I love the Moral Tales, it is not because I approve of their diffident wives or their dutiful endings: it is because they pay apt homage to those sublime and singular instants when a normal interaction lifts off into a gorgeous rapport, like a plane pushing up off the ground.

According to the experts, then, I love Rohmer for all the wrong reasons. Roger Ebert, who takes the standard and sensible view, maintains that “the final scene in Chloe” is Rohmer’s “last comment on the series.” He concludes that the director is instructing us to “stop playing games and embrace each other with honesty.”[6] The triumph of Hélène over Chloé represents the triumph of moral imperative over wanton impulse, of good over evil, of marriage over dalliance. Rohmer was an admirably subtle filmmaker, never sanctimonious or judgmental, but I think it is likely that he would have affirmed something like Ebert’s reading, albeit in less overtly didactic terms. When someone asked him how he was able to withstand the charms of the young actresses he mentored, he answered, “My secret is absolute chastity.”[7]

Then again, chastity is not always a tactic of the virtuous. At its best, it is merely a prelude to purer perversions.

• • •

In “The Last Lover,” a 1958 review of Lolita, the critic Lionel Trilling opens with a shocking speculation: “I think that the real reason why Mr. Nabokov chose his outrageous subject matter is that he wanted to write a story about love.”[8] He goes on to argue, offensively and brilliantly, that Nabokov wrote about pedophilia so as to resuscitate the traditional love story.

He begins with a nod to the genre’s primogenitor: the courtly romance. In early romances, Trilling maintains, “the possibility of love could exist only apart from and more or less in opposition to marriage “Passion-love,” the sort of ardor that marriage dulled, arose “beyond the pale of society.” It could last only as long as it was illicit: to institutionalize it was to render it ordinary and polite, to sap its vital forces. Adulterous couples like Tristan and Iseult or the famous Lancelot and Guinevere qualified as lovers because they were “captivated by a reality and a good that are not of the ordinary world,” not unlike Rohmer’s fervent Catholics.

But a contemporary novelist who aspires to “maintain the right conditions for a story of passion-love” confronts a challenge, for we live in a shameless society. If “love requires scandal,” and nothing scandalizes us any longer, how is the novelist to cast lovers beyond the bounds of respectability, which is to say, how is the novelist to render lovers at all? These days, garden-variety adultery is not sufficient: it has become too commonplace, too much of a counter-institution. Lolita goes further because it has to go further in order to induce the bygone frissons.

Likely unbeknownst to its author, Trilling’s proposal echoes an idiosyncratic and ingenious theory propounded in print just one year earlier. In the lunatic, luminous Erotism, published in 1957, the libertine philosopher Georges Bataille suggests that eroticism is a question of the violation of social prohibitions. If everything is permitted, then nothing is perverted. Advocates of free love, the seeming allies of pleasure, are in fact its most dangerous adversaries: when bohemians “ceased to believe in Evil,” Bataille writes, they precipitated “a state of affairs in which, since eroticism was no longer a sin and since they could no longer be certain of doing wrong, eroticism was fast disappearing.”[9] Without violation, there is no rapture; without taboo, there is no violation; and without restriction, there is no taboo. In Bataille’s terms, “the sacred”—the erotic, with all its attendant dishevelments and divestments of self—requires “the profane,” the mundane mores constraining our everyday behavior. The profane is less exalted than the sacred, but it is equally necessary: each perfects the other. A curious consequence of this view is that the more repressive and puritanical a culture, the more considerable its erotic potential. The best sex, probably, was the sex people had when they really believed they would go to hell for it—but craved it so badly that they had it anyway.

One way to recover eroticism in an era of unabashed philandering is to seek ever more extreme satisfactions, as did Nabokov in Lolita—and as did Bataille in his notoriously twisted work of erotica, The Story of the Eye, a slim volume in which an enucleated eyeball is inserted into a woman’s vagina. But another way to recover eroticism is to recover restraint. Rohmer raises the stakes of adultery until it becomes a scandal again. This is how he recuperates love, which after all can only exist in the afternoon, just as movies can only exist in abeyance from the daily drudgeries. Rohmer’s films, like his character’s almost affairs, are much too marvelous to carry over into normal life, much too fantastic for lasting realization. But just as the extravagance of love requires a foil in the form of monotonous marriage, cinematic effusions require a foil in the form of bruising, unartistic reality. Chastity (and life at its least aesthetic) can, if we let it, exist in the service of something better, something as impossible to retain or fully consummate as it is to forgo.

No doubt Rohmer would protest that I am getting everything backwards—that Hélène is real, while Chloé is mere fantasy, that art exists in the service of a reality God has arranged and polished. But in the end, who is really most essential, the man at home without a telephone, or the man making the movies? Was it Rohmer or Schérer who represented the sinful temptation, Rohmer or Schérer who represented the quotidian doldrums? Or did one require the other, as the sacred requires the profane and the profane requires the sacred? Did the person who was both Schérer and Rohmer manage what the rest of us cannot—did he live two lives at once, simultaneously and perfectly?

- Richard Brody, “The Film in Which Eric Rohmer Let Desire Win,” The New Yorker, 26 August 2015. Available at newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/the-film-where-eric-rohmer-let-desire-win.

- Eric Rohmer, “New Interview with Eric Rohmer,” trans. Daniel Fairfax, Senses of Cinema, no. 54 (April 2010). Originally published in French in Cahiers du Cinéma, no. 219 (April 1970). Available at sensesofcinema.com/2010/feature-articles/new-interview-with-eric-rohmer.

- Ibid.

- Eric Rohmer, “Letter to a Critic,” in Rohmer, The Taste for Beauty, comp. Jean Narboni, trans. Carol Volk (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 81.

- Eric Rohmer, “New Interview with Eric Rohmer.”

- Roger Ebert, “Chloe in the Afternoon,” RogerEbert.com (originally in the Chicago Sun-Times), 28 December 1972. Available at rogerebert.com/reviews/chloe-in-the-afternoon-1972.

- Quoted in Antoine de Baecque and Noël Herpe, Éric Rohmer: A Biography, trans. Steven Rendall and Lisa Neal (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), p. 3.

- This and all subsequent Trilling quotations are from Lionel Trilling, “The Last Lover,” The Moral Obligation to Be Intelligent: Selected Essays, ed. Leon Wieseltier (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2000), pp. 364, 365, 368, 367, 368, and 367, respectively.

- Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality, trans. Mary Dalwood (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1986), p. 128.

Becca Rothfeld is a contributing editor at The Point and a PhD candidate in philosophy at Harvard University. She is at work on an essay collection for Metropolitan Books.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.