Cybernetic Revolutionaries

Technology and politics in Allende’s Chile

Eden Medina

In July 1971, the British cybernetician Stafford Beer received an unexpected letter from Chile. Its contents would dramatically change Beer’s life. The writer was a young Chilean engineer named Fernando Flores, who was working for the government of newly elected Socialist president Salvador Allende. Flores wrote that he was familiar with Beer’s work in management cybernetics and was “now in a position from which it is possible to implement on a national scale—at which cybernetic thinking becomes a necessity—scientific views on management and organization.”[1] Flores asked Beer for advice on how to apply cybernetics to the management of the nationalized sector of the Chilean economy, which was expanding quickly because of Allende’s aggressive nationalization policy.

Less than a year earlier, Allende and his leftist coalition, Popular Unity (UP), had secured the presidency and put Chile on the road toward socialist change. Allende’s victory resulted from the inability of previous Chilean governments to resolve such problems as economic dependency, economic inequality, and social inequality using less drastic means. His platform made the nationalization of major industries a top priority, an effort Allende later referred to as “the first step toward the making of structural changes.”[2] The nationalization effort would not only transfer foreign-owned and privately owned industries to the Chilean people, it would also “abolish the pillars propping up that minority that has always condemned our country to underdevelopment,” as Allende referred to the industrial monopolies controlled by a handful of Chilean families.[3] The majority of parties in the UP coalition believed that by transforming Chile’s economic base, they would subsequently be able to bring about institutional and ideological change within the nation’s established legal framework, an approach that set Chile’s path to socialism apart from that of other socialist nations, such as Cuba or the Soviet Union.[4]

Flores worked for the Chilean State Development Corporation, the agency responsible for leading the nationalization effort. Although only twenty-eight when he wrote Beer, he held the third-highest position in the development agency and a leadership role in the Chilean nationalization process. Beer decided he wanted to do more than simply offer advice, and his response to Flores was understandably enthusiastic. “Believe me, I would surrender any of my retainer contracts I now have for the chance of working on this,” Beer wrote. “That is because I believe your country is really going to do it.”[5] Four months later, the cybernetician arrived in Chile to serve as a management consultant to the Chilean government.

The history of cybernetics is filled with curious characters, and Stafford Beer was no exception. He wore a long beard for much of his life, habitually smoked cigars, and drank whiskey from a hip flask while discussing scientific ideas late into the night. His interests spanned Eastern philosophy, neuroscience, and management, and his writings addressed subjects as diverse as economic development, socialism, management science, terrorism, and even tantric yoga; he often included his own poetry and drawings in his scientific publications. Described as a “swashbuckling pirate of a man,” a “cross between Orson Welles and Socrates,” and a guru, later in his life he gave up many of his material possessions and lived in a small cottage in Wales lacking running water, central heating, and a telephone line.[6]

Nevertheless, Beer always identified himself first as a cybernetician. He had read Norbert Wiener’s book Cybernetics a few years after its publication in 1948 and it had had an enormous influence on him. Cybernetics, which Wiener defined as the study of “control and communication in the animal and the machine,” brought together ideas from across disciplines—mathematics, engineering, and neurophysiology, among others—and applied them toward understanding the behavior of mechanical, biological, and social systems.[7] The interdisciplinary scope of the new field appealed to Beer, and he saw how such concepts could be applied to industrial management. He created a new definition of cybernetics that better fit his work in management: it became the “science of effective organization.” And while Beer drew from Wiener and other major figures in cybernetic history, his focus on management and his willingness to apply cybernetic concepts to government organizations and political change set him apart from other prominent members of the field.

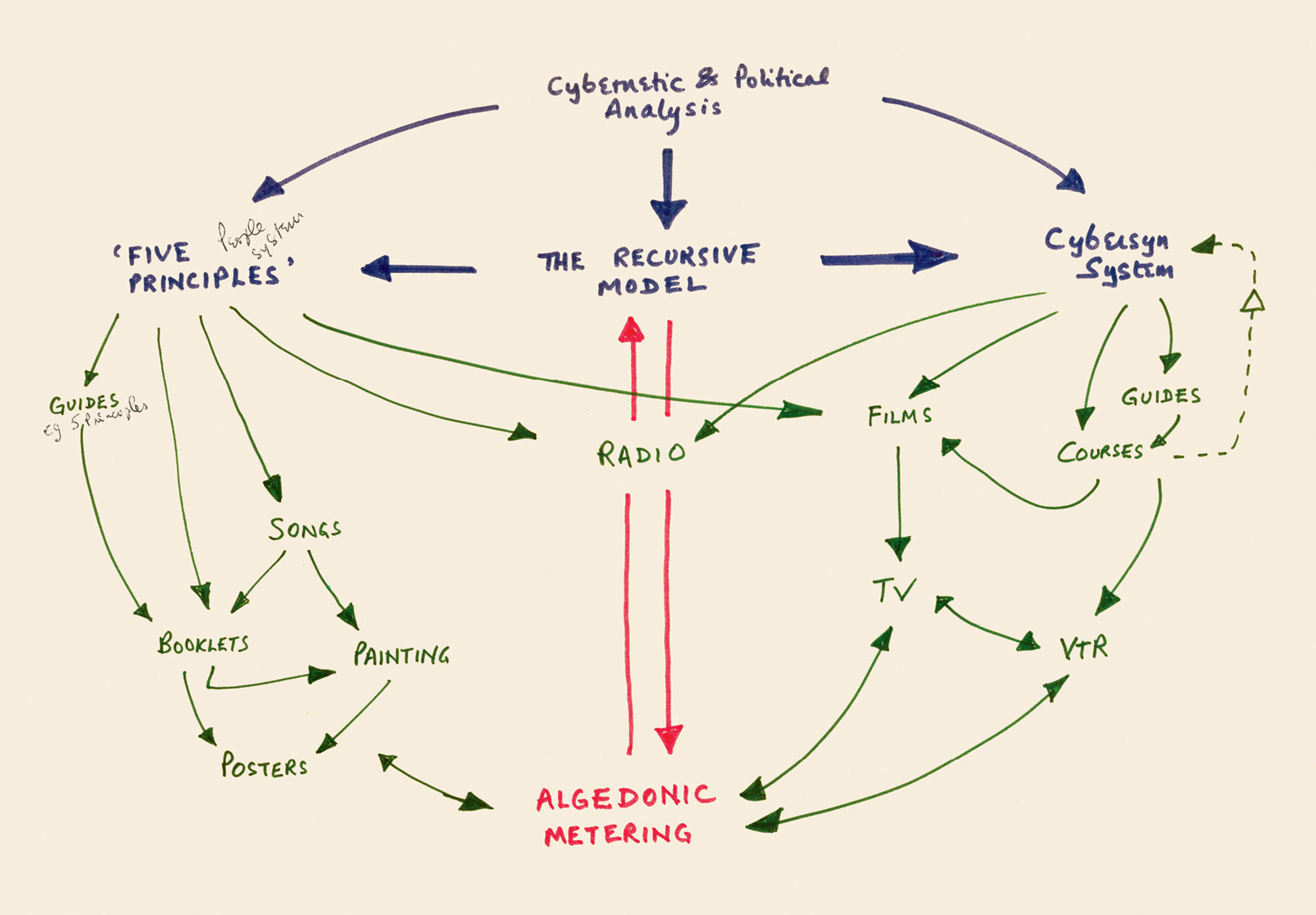

Now Flores was offering Beer a chance to apply his ideas on management at a national level during a moment of political transformation, and Beer found the invitation irresistible. This connection between a Chilean technologist working for a socialist government and a British consultant specializing in management cybernetics would lead to Project Cybersyn, an ambitious effort to create a technological system to manage the Chilean national economy in close to real time using a mainframe computer running customized software and a network of telex machines. The system addressed difficult engineering problems such as real-time control, modeling the behavior of dynamic systems, and computer networking. It pushed the boundaries of what was possible in the early 1970s using Chile’s limited technological resources.

Beer arrived in Chile on Tuesday, 4 November 1971, the first anniversary of the Allende government. On 12 November, Beer met Allende for the first time. Accompanied only by Roberto Cañete, his interpreter, Beer entered the presidential palace while the rest of his team waited anxiously at a bar across the street in the Hotel Carrera. “A cynic could declare that I was left to sink or swim,” Beer later remarked. “I received this arrangement as one of the greatest gestures of confidence that I ever received; because it was open to me to say anything at all.”[8]

According to Beer and Cañete, the meeting went quite well.[9] Once Beer and Allende were sitting face to face (with Cañete in the middle, discreetly whispering translations in each man’s ear), Beer began to explain his work in management cybernetics and the Viable System Model, which he had developed to describe the balance between centralized and decentralized forms of control in organizations. The model was based on the human neurosystem and provided a conceptual framework for the design of Project Cybersyn. Allende, who had trained as a pathologist, immediately grasped the biological inspiration for Beer’s cybernetic model and nodded knowingly throughout. This reaction left quite an impression on the cybernetician: “I explained the whole damned plan and the whole Viable System Model in one single sitting … and I’ve never worked with anybody at the high level who understood a thing I was saying.”[10] Beer knew he would have to be persuasive. He acknowledged the difficulties of achieving real-time economic control but emphasized that a system based on a firm understanding of cybernetic principles could, even with Chile’s limited technological resources, accomplish technical feats deemed impossible in the developed world. Once Allende became familiar with the mechanics of Beer’s model, he began to reinforce the political implications of the project and insisted that the system behave in a “decentralizing, worker-participative, and anti-bureaucratic manner.”[11] These words stayed with Beer and convinced him that the system needed to be more than a toolbox for technocratic management; it needed to create social relations that were consistent with the political ideals of the Allende government.

When Beer finally brought his discussion around to the top level of his systematic hierarchy, the place in the model that he had reserved for Allende himself, the president leaned back in his chair and said, “At last, the people.”[12] With this succinct utterance, Allende reframed the Cybersyn project to reflect his ideological convictions and view of the presidential office, which often equated his political leadership with the rule of the people.

Beer spent the remainder of his November 1971 visit studying the Chilean economy and drafting a concrete articulation of a computer system the government might use to address the problem of economic management. The system consisted of four subprojects: a telex network; software for statistically detecting economic anomalies and predicting future behavior; an economic simulator; and a futuristic operations room. By January 1973, Beer and his team had built a working prototype of each of these components, with the exception of the economic simulator.

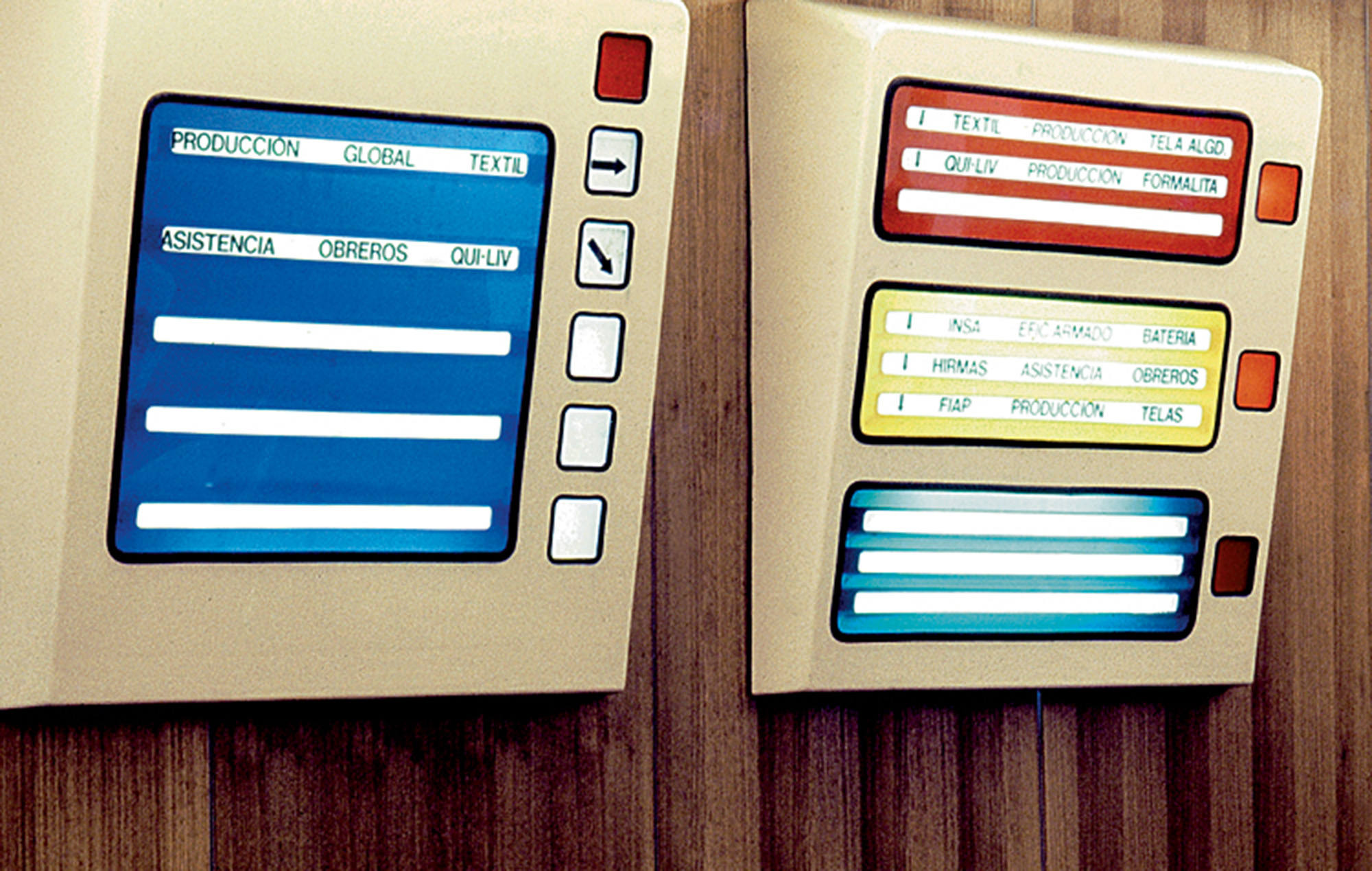

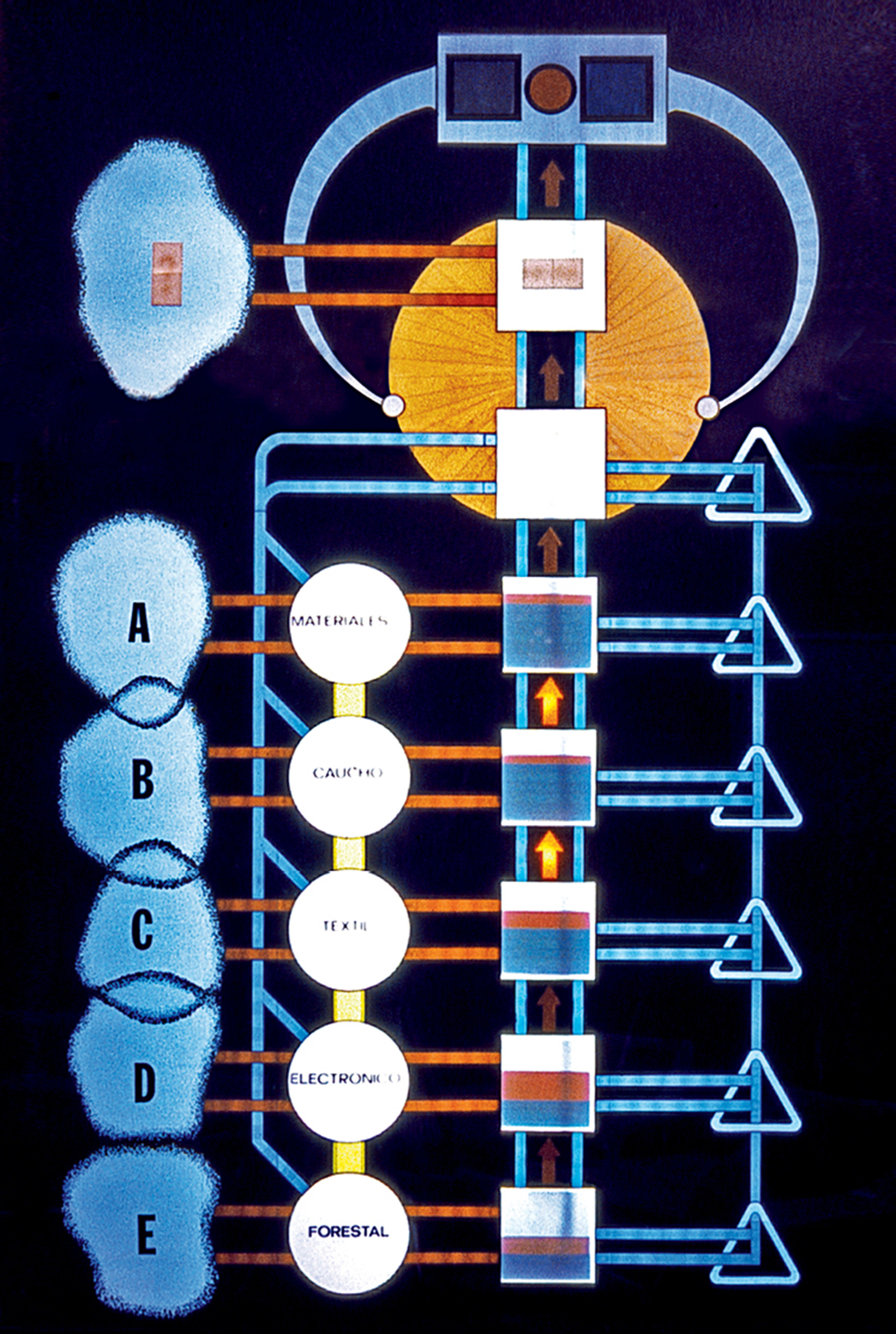

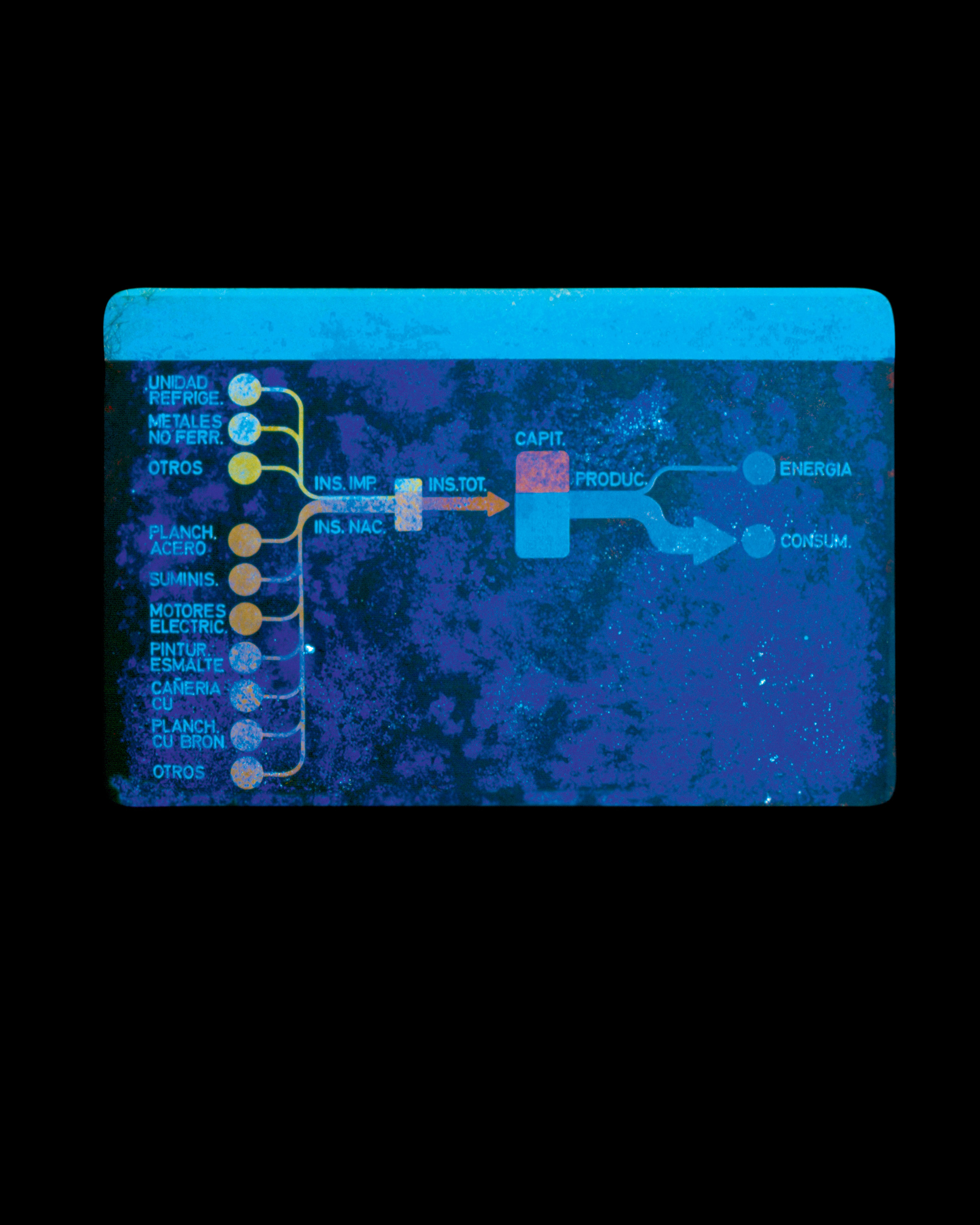

Visually, the operations room best captures the idea of an alternative socialist modernity that the project represented. Members of Chile’s Grupo de Diseño Industrial, the country’s first state-run industrial design group, created the room under the direction of Gui Bonsiepe, a former member of the Ulm School of Design. The room fit with the political mandate of the Grupo de Diseño Industrial, but it was unlike anything else it created. While its other projects were closely tied to the day-to-day life of the Chilean people, the room was more of a futuristic dream. However, it did incorporate elements characteristic of the Ulm School and reflected the merging of engineering and design that had taken place at Santiago’s Catholic University and later at the State Technology Institute (INTEC), where the group was based. The designers paid great attention to ergonomics and concerned themselves with such questions as the best angle for a user to read a display screen. They studied aspects of information visualization and wondered how they could use color, size, and movement to increase comprehension or how much text could be displayed on a screen while maintaining legibility. The operations room offered a new image of Chilean modernity under socialism, a futuristic environment for control that meshed with other, simultaneous efforts to create a material culture that Chileans could call their own.

The designers originally wanted to make the room circular, but when this proved difficult, they opted for a hexagon, a configuration that permitted five distinct wall spaces for display screens plus an entrance.[13] Upon entering the room, a visitor would find that the first wall to the right opened up into a small kitchen. Continuing around the room, the second wall contained a series of four “datafeed” screens, one large and three small, all housed in individual cabinets made of fiberglass, a relatively new construction material that lent itself to organic curved shapes difficult to achieve with more traditional building materials. The large screen was positioned above the three smaller screens and displayed the combination of buttons a user needed to push on the armrest of his chair—also made of fiberglass—to change the data and images displayed on the three screens below. The armrest also included a hold button that, when pushed, gave that user control over the displays until the button was released. A series of slide projectors placed behind the wall were used to back-project images onto the datafeed screens, thus simulating flat-panel displays. The armrest buttons sent signals to the different projectors and controlled the position of the slide carrousel. Slides displayed economic data or photographs of production in the state-run factories.[14] Rodrigo Walker, a member of the design group who worked on the operations room, said the user’s ability to create his own path through the data was “like a hypertext” but one that preceded the invention of the World Wide Web by more than twenty years. While the parallel with the Web is not exact, the room did offer a nonlinear way of seeing the Chilean economy that broke from the presentation of data in traditional paper reports.[15]

The Chilean government dedicated some of its best resources to the room’s completion. Its futuristic sensibility, which borders on science fiction, was unlike anything being built in Chile at the time. It is often compared with the style of design found in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), although the room’s creators vehemently dispute that they were influenced by sci-fi films. However, using new materials such as plastic and fiberglass allowed them to project a new image of socialist modernity that rivaled science fiction.

Beer proposed that Allende inaugurate the room, and even drafted a sample speech for the president to deliver at the event, but it would never be given. The speech contained such sentiments as “[We] set out courageously to build our own system in our own spirit. What you will hear about today is revolutionary—not simply because this is the first time it has been done anywhere in the world. It is revolutionary because we are making a deliberate effort to hand to the people the power that science commands, in a form in which the people can use it.”[16] Allende never inaugurated the Cybersyn operations room, but he did visit the space at the end of 1972. On 30 December, Flores brought Allende and General Carlos Prats, the minister of the interior, to the operations room. The president sat in one of the futuristic chairs and pushed a button on the armrest. A small moment, yes, but one that presents a new reading of Chilean socialism because it differs from the images of protests, public speeches, and community activities that typically define the Allende period.

The operations room was only a prototype, but other parts of the system were put to use by the government to help it survive moments of political crisis. In October 1972, forty thousand truck owners went on strike nationwide to protest the government. The truck owners refused to distribute food, fuel, or raw materials for factory production, as well as other essential goods, and they blocked roads, sometimes violently, thus prohibiting others from passing. Additional business associations, or gremios, voiced their support for the truck owners in the days that followed, and locked out their own workers and clients. At the same time, members of the right stepped up their efforts to hoard or destroy basic consumer goods, exacerbating consumer shortages and antigovernment sentiment among the Chilean people. With substantial financial support from the US government, the strikers appeared poised to make good on their promise to shut down the country indefinitely.

In response, Flores proposed setting up a central command center in the presidential palace that would bring together the president, the cabinet, the heads of the political parties in the Popular Unity coalition, and representatives from the National Labor Federation. Once these key people were brought together in one place and apprised of the national situation, Flores reasoned, they could then reach out to the networks of decision makers in their home institutions and get things done. This human network would help the government make decisions quickly and thus allow it to adapt to a rapidly changing situation. In addition to the central command hub in the presidential palace, Flores established a number of specialized command centers dedicated to transportation, industry, energy, banking, agriculture, health, and the supply of goods. Telex machines, many of which were already in place for Project Cybersyn, connected these specialized command centers to the presidential palace.[17] Beer estimated that the telex network transmitted two thousand messages daily during the strike. The network helped the Chilean government assess the rapidly changing strike environment as well as adapt and survive—much like the biological organisms from which Beer drew inspiration in his cybernetics. Both Cybersyn team members involved with the telex network and people outside the project team who used the network during the crisis agree that the network helped the government survive the October Strike until it ended on 2 November.

Cybersyn’s connection to a socialist government at the height of the Cold War caused the system to be criticized by both international and Chilean media outlets. For example, on 7 January 1973, the Observer, the United Kingdom’s oldest Sunday newspaper, brought Project Cybersyn to the attention of the English-speaking public with the provocative headline “Chile Run by Computer.” The Observer article portrayed the system in a way that was both damaging and untrue. It claimed, “The first computer system designed to control an entire economy has been secretly brought into operation in Chile,” and described it as having been “assembled in some secrecy so as to avoid opposition charges of ‘Big Brother’ tactics.”[18] In the US, the St. Petersburg Times reprinted the Observer story but added its own embellishment: a cartoon mainframe computer using binoculars to watch a small man in a Mexican sombrero—a misrepresentation of both Project Cybersyn and the Chilean people.[19] In Chile, the center-right magazine Qué Pasa ran an article with the headline “Secret Plan ‘Cyberstride’: Popular Unity Controls Us by Computer.”[20] The article stressed that Project Cybersyn would “not only be used for economic ends, but also for political strategy,” and it transformed the cybernetic phrase “communication is control” into something that sounded sinister. The article concluded by taking a jab at the ailing Chilean economy: “It is not clear if inflation, shortages, the black market and long lines have been studied by the ‘Cyberstride’ computers.”[21] Not only did Project Cybersyn, and by extension the Chilean government, threaten political freedom, it also was not qualified to fix the broad scope of Chile’s economic problems. Such press accounts reflected Cold War fears of Soviet expansion in developing nations such as those in Latin America and opposition critiques of the Allende government. They demonstrate how international geopolitics colored views of this technological system.

On 11 September 1973, the Chilean military launched a coup against the Allende government that ended Chile’s experiment with peaceful socialist change and resulted in Allende’s death. The military stopped work on Project Cybersyn after the coup and either abandoned or destroyed the work the team had completed. In some instances, Cybersyn’s destruction was brutal and complete. One member of the military took a knife and stabbed each slide the graphic designers had made to project in the operations room. Other military officials adopted a more inquisitional approach. They summoned members of the project team, as well as other Chilean computer experts who had not been involved in the project, and questioned them about the system. However, military interest in the project soon waned.

And in the context of the new military government, Project Cybersyn no longer made sense. It was a system designed to help the state regulate the nationalized economy and raise production without unemployment. By 1975, the military had decided to back the neoliberal “shock treatments” proposed by the “Chicago Boys,” a group of economists who had studied either with Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago or with professors at the Catholic University in Santiago who were well versed in Friedman’s monetarist economic theories. The plan for the economy called for continuing cuts to public spending; freezing wages; privatizing the majority of the firms nationalized by the government; reversing the agrarian reform carried out during the Allende administration (or reshaping it by selling Chilean farmlands to agribusiness); and laying off eighty thousand government employees. Project Cybersyn had formed part of Chile’s utopian dream for peaceful socialist change. That dream was now over.

This is an adapted excerpt from Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende’s Chile (The MIT Press, 2012).

- Fernando Flores, letter to Stafford Beer, 13 July 1971, box 55, Stafford Beer Collection, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, UK.

- Salvador Allende, quoted in Régis Debray, Conversations with Allende: Socialism in Chile (London: New Left Books, 1971), p. 85.

- Salvador Allende, “The Purpose of Our Victory: Inaugural Address in the National Stadium, 5 November 1970,” in Allende, Chile’s Road to Socialism, ed. Joan E. Garcés, trans. J. Darling (Baltimore: Penguin, 1973), p. 59.

- Sergio Bitar, Chile: Experiment in Democracy (Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues, 1986).

- Stafford Beer to Fernando Flores, 29 July 1971, box 55, Beer Collection.

- Jonathan Rosenhead, telephone interview by Eden Medina, 8 October 2009; Michael Becket, “Beer: The Hope of Chile,” Daily Telegraph, 10 August 1973, p. 7.

- Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1965), p. 11. This is the definition that Wiener uses in his book. However, he was not the lone inventor of the term. In the text he describes being part of a group of scientists who expressed frustration with existing terminology to describe the new field and its central areas of concern and were thus “forced to coin at least one artificial neo-Greek expression to fill the gap” (p. 11).

- Stafford Beer, Brain of the Firm: The Managerial Cybernetics of Organization, 2nd ed. (New York: J. Wiley, 1981), p. 257.

- When I interviewed Beer in 2001, he gave a detailed account of his meeting with Allende, which I have summarized here. Thus Allende’s responses come to us through the filter of Beer’s memory thirty years after the meeting took place, and through Beer’s account in Brain of the Firm, published ten years after the meeting. Still, the vividness of Beer’s oral account indicates that the meeting left a lasting impression on him. Cañete confirmed Beer’s account when I interviewed him in 2003.

- Stafford Beer, interview by Eden Medina, 15–16 March 2001, Toronto, Canada.

- Quoted in Stafford Beer, Brain of the Firm, op. cit., 257.

- Ibid., 258. This account draws on Beer’s account in Brain of the Firm, my 2001 interview with Beer, and my interview with Roberto Cañete, Viña del Mar, Chile, 16 January 2003.

- Gui Bonsiepe, interview by Eden Medina, 21 May 2008, La Plata, Argentina.

- For a detailed description of the operations room design, see Grupo de Proyecto de Diseño Industrial, “Diseño de una sala de operaciones,” INTEC, no. 4 (1973), pp. 19–28.

- Rodrigo Walker, interview by Eden Medina, 24 July 2006, Santiago, Chile.

- Stafford Beer, “Welcome to the Operations Room,” n.d., box 63, Beer Collection.

- These command centers were not all in the same location; some were established in the State Development Corporation and the Ministry of Economics, in addition to the presidential palace. However, the State Development Corporation had the greatest capacity for sending and receiving messages because of the telex network created for Project Cybersyn.

- Nigel Hawkes, “Chile Run by Computer,” Observer, 7 January 1973.

- Nigel Hawkes, “The Age of Computers Operating Chilean Economy,” St. Petersburg Times, 17 January 1973.

- Cyberstride was the name of the software that ran on Cybersyn’s computers.

- “Plan Secreto ‘Cyberstride’: La UP nos controla por computación,” Qué Pasa, 15 March 1973.

Eden Medina is associate professor of informatics and computing and adjunct associate professor of history at Indiana University, Bloomington. Her second book, the co-edited Science and Technology Studies in Latin America: Beyond Imported Magic, is forthcoming from the MIT Press. More information about her book Cybernetic Revolutionaries can be found at http://www.cyberneticrevolutionaries.com [link defunct—Eds.].

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.